Chernobyl 30 Years On: Work On Giant Confinement Structure Set To Replace Ageing Sarcophagus Nears End

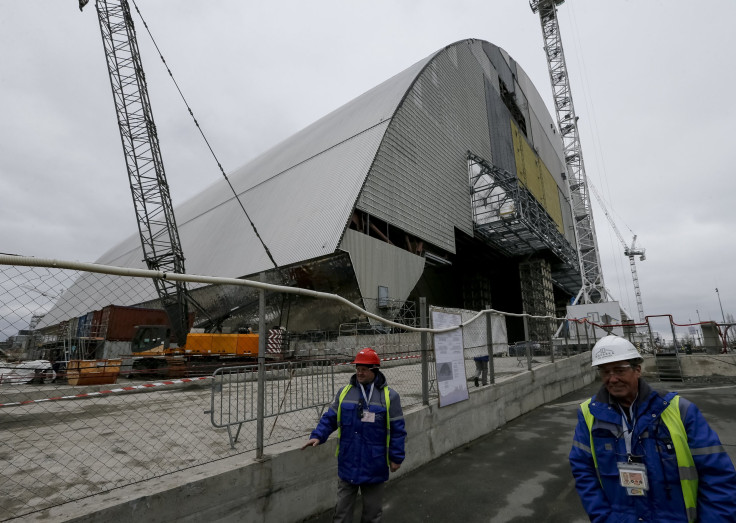

In the months immediately after a flawed reactor design triggered the world’s worst nuclear disaster in the Ukrainian city of Chernobyl, engineers and construction workers hurriedly built a steel and concrete “sarcophagus” to enclose the doomed site and prevent radiation leak. Now, as the 30th anniversary of the incident approaches, on April 26, workers at the site are rushing to replace the hastily constructed and ageing structure with another protective shell, named the New Safe Confinement (NSC).

Once the construction work is completed, the gigantic arch, made of stainless steel, will be the largest movable structure ever built.

“The new structure will also be an extraordinary landmark, tall enough to house London’s St Paul’s or Paris’ Notre Dame cathedrals, To minimize the risk of workers’ exposure to radiation, it is being assembled in the vicinity of the site and then slid into position,” the European Bank of for Reconstruction and Development, which in one of the main funders of the project, says in a statement published on its website.

Work on the NSC, which its builders say would have a life span of at least 100 years, began in 2010 and is expected to be completed sometime during 2017. Once finished, it weigh over 30,000 tons and rise to a height of over 100 meters.

“When completed, the New Safe Confinement will prevent the release of contaminated material from the present shelter and at the same time protect the structure from external impacts such as extreme weather,” the European Bank of for Reconstruction and Development said in the statement. “It will be strong enough to withstand a tornado and its sophisticated ventilation system will minimise the risk of corrosion, ensuring that there is no need to replace the coating and expose workers to radiation during the structure’s lifetime.”

The Chernobyl disaster spewed out huge quantities of the radioisotopes caesium-137 and iodine-131. According to some estimates, the accident released 5,300 PetaBecquerels of radiation — nearly 10 times more than the amount released during Japan’s Fukushima disaster in 2011.

Long-term exposure to radiation can lead to severe illnesses. Iodine-131, for instance, can increase risk of thyroid cancer, especially for those exposed as children. Studies conducted in the past have found an uptick in mortality among irradiated populations in the region, and increased risk of cataracts and mental health effects.

Although the levels of radiation throughout the 1,000 square mile exclusion zone around the Chernobyl nuclear plant have dropped significantly over the past three decades, recent studies have shown that people inhabiting the region are still coming in daily contact with dangerously high levels of radiation.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.