Childhood Lead Exposure Not Linked To Adult Criminal Behavior: Study

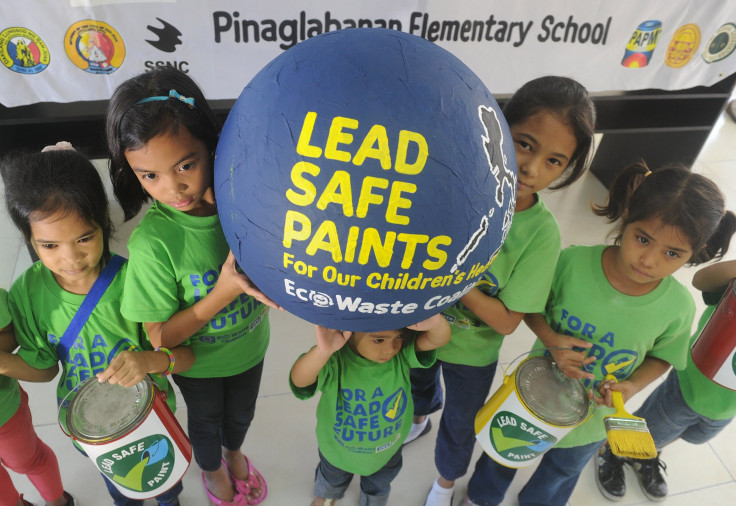

Lead is a toxic for kids, and exposure the metal early in a child’s life can be detrimental to brain development and prolonged exposure can even prove fatal.

As recently as 2015, there have been lead related child death epidemics.

Over the years a myth had gained traction that kids who were exposed to lead grew up to become juvenile delinquents. The lead-crime hypothesis claims that elevated lead level at an early age causes a spike in criminal activity later in life.

But, now a team of researchers have found no direct link between childhood lead poisoning and delinquency later in life.

According to a comprehensive new study that tracked the lives of hundreds of lead-exposed New Zealand children born in the early 1970s showed the team that the link to delinquency is just a myth.

The levels of exposure among kids from New Zealand was found to be very high. Not only that, unlike other countries where the most affected were the poor, in NZ every sector of the society was hit, giving the researchers a varied study group. This set helped the team counter the nagging socio-economic problems in past data.

The results of the study showed the team that the findings "failed to support" the popular notion that a child's later criminal activity rises with higher exposure to the metal.

According to the team led by Amber Beckley, of Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, the study proved that the effects of lead were restricted to childhood alone and did not contribute to delinquency at later stages.

The team analysed 553 individuals born between 1972-1973 from all socioeconomic groups. These individuals were observed till they turned 38.

The team first looked at blood lead level readings from the data that had been taken when the study participants were just 11 years old. The team then looked at any history of criminal behavior years later when the average age of the same group was 38 years old.

"It is most commonly found in lead-based paint used in old homes, particularly those built before 1978," said Dr. Sophia Jan, who directs pediatrics at Cohen Children's Medical Center in New York, in a NewsDay release. "However, lead can be found in the water pipes of old homes, gasoline and many other environmental sources," she added.

All past data failed to account for the number of people in poverty and also did not contain data varied enough for the overall effects to be studied. In the United States, for example, kids from poorer households are more vulnerable to exposure to lead just like in most places across the world.

"The study's greater value lies in its ability to remove socioeconomic class as a variable," said Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, in the release.

"Adverse neurological effects related to learning and memory have been clearly established," he added, stating that the study does not take away the fact that lead is toxic and will prove detrimental to a child's health.

The researchers found no indication that those who had been exposed to high levels of lead at age 11 were more likely to have an adult criminal record or to have reported having engaged in recurring criminal activity and/or violent behavior.

"Previously detected associations between blood lead levels and criminal offending may be owing to the toxic effect of lead disproportionately affecting disadvantaged groups," the study authors added in the report.

The findings were published online Dec. 26 in JAMA Pediatrics.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.