Christie's Pension Overseer Invested New Jersey Money In Fund He Is Linked To Privately

In the context of a New Jersey pension system stocked with $81 billion in assets, here was a transaction that seemed unremarkable. It was 2011, the year after Gov. Chris Christie had installed his longtime friend Robert Grady to oversee the state pension fund’s investments. A former executive from the heights of finance and a national Republican Party power broker, Grady was pursuing a new strategy, shifting money into hedge funds and private equity holdings in the name of diversification and higher returns. He was now pushing to entrust up to $1.8 billion of New Jersey pension money to the Blackstone Group, one of the largest players in private equity.

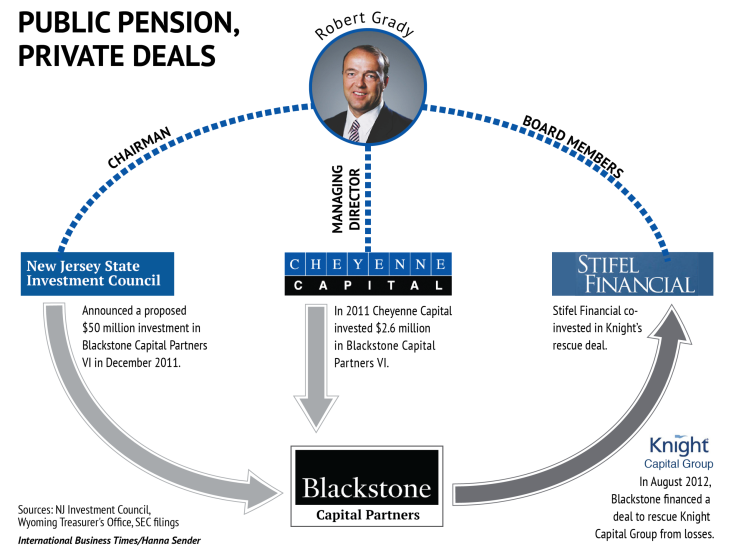

But one special feature of that Blackstone bet underscores the interlocking relationships at play as states increasingly rely on the counsel and management of Wall Street institutions to invest their pension dollars: One of the private equity funds New Jersey was investing in – a pool of money called Blackstone Capital Partners VI – claimed among its investors a Wyoming-based company named Cheyenne Capital. That company's list of partners included one Robert Grady.

In short, Grady was pushing to invest New Jersey public money in the same Blackstone fund in which his own firm was investing -- without disclosing that fact to N.J. officials.

This sort of arrangement is generally anathema in the realm of public pension oversight, where state rules often bar public officials from being involved in investments in which they or their companies have a financial interest.

Such rules aim to protect public funds from being used to grease the wheels for private deals. Without such strictures, a private equity firm might be tempted to court managers of state pension funds by giving them their own piece of the action in exchange for delivering public money on terms less-than-optimal for taxpayers. Managers of state pension money might, say, be rewarded with lower fees on their own investments while agreeing to turn over public pension money to be managed at higher fees.

Taxpayers are especially vulnerable to potential abuses when the investments at issue are private equity transactions. Unlike investments in publicly traded stock, the terms of private equity deals are secret, meaning taxpayers have no reliable way of learning whether they are buying in on the same terms as private investment firms.

In the case of New Jersey, Blackstone Capital Partners VI and Cheyenne Capital, only the insiders know the details of how the money changed hands: Exact terms have been kept secret. None of these institutions has disclosed its contracts.

But current and former financial executives and government officials say the mere existence of an arrangement in which the chairman of New Jersey’s State Investment Council was moving state funds into a vehicle his firm was investing in presents a troubling conflict of interest -- especially in a state with relatively tough rules governing this area.

“It definitely gets an official into an ethically grey area when, in his fiduciary capacity working for the government, he recommends investments where he has a direct financial interest,” said Marshall Auerback, a former hedge fund manager who has provided investment advice to the city of Denver and is now the director of institutional partnerships at the Institute for New Economic Thinking, a research center funded by investor George Soros. “It puts the official in a classic conflict-of-interest situation. It may well have been a perfectly legit transaction that benefited the state, but the optics stink."

Grady defended his actions while rejecting any inference of impropriety.

“There is no benefit derived, and there is no conflict,” he said in an emailed statement, declining a request for an interview. Despite his ownership stake in Cheyenne Capital, he asserted: “I have no economic interest in Cheyenne Capital's investment in Blackstone VI.”

Cheyenne Capital said it had entered into an arrangement with Grady that ensured he would not be placed in a conflict of interest, one that effectively walled him off from Blackstone VI.

“Cheyenne Capital agreed with Bob Grady at the outset that he would have no interest in Cheyenne Capital’s investment in Blackstone VI,” the company said in a statement to International Business Times.

Cheyenne did not respond to IBTimes' request for documents that might verify the existence of such an agreement. Cheyenne also did not respond to a request to release the text of its arrangement with Blackstone, nor to a request to explain how it was possible for Grady to own a piece of Cheyenne without having an economic interest in Blackstone VI.

Experts asked to assess Grady's distinction pronounced it effectively irrelevant.

“Whether or not he has a direct piece of the action from this particular investment, he is a partner in the company that is going to benefit from the investment,” said Eileen Appelbaum, an economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and author of the book “Private Equity at Work.” “If the investment in Blackstone turns out to be profitable, his company is going to benefit from that.”

In New Jersey, executive branch documents say conflict-of-interest rules prohibit state officials from being involved "in any official matter" in which they have "a direct or indirect personal or financial interest.” The rules also say that no state official "should act in his official capacity in any matter wherein he has a direct or indirect personal financial interest that might reasonably be expected to impair his objectivity or independence of judgment."

Concerns about possible conflicts influencing pension investment decisions have in recent years gained political currency. Two years ago, state lawmakers in Christie's own Republican Party proposed strengthening conflict-of-interest penalties specifically for those serving on the State Investment Council, the body chaired by Grady.

Gov. Christie's office did not respond to IBTimes' request for comment.

Thomas Byrne, the Christie-appointed vice-chairman of the New Jersey State Investment Council, told International Business Times that Grady, who is also the Chairman of the Governor's Council of Economic Advisers, acted purely in the state's interest.

“All I can say for now is that Bob Grady is a person of the highest integrity who has not benefitted economically from transactions in Blackstone VI or other transactions done by the state,” Byrne said.

But within some quarters of the Republican Party, lawmakers have grown concerned enough about apparent conflicts of interests coloring pension investments that they are seeking tougher rules. One New Jersey lawmaker, Joe Pennacchio, a Republican, joined his GOP colleagues in 2012 to push a bill that would stiffen penalties for State Investment Council members who violate conflict-of-interest laws.

“There has to be a lot more transparency,” Pennacchio told IBTimes. “Any time public dollars are involved, total transparency should be involved. Those are public dollars. You should be ready to answer questions when they are using public dollars -- exactly what, when, where and how. At a minimum, the taxpayers and pensioners deserve that.”

Overlapping Interests

The investment that would create a nexus between Cheyenne Capital and New Jersey's pension fund dates back to December 2011. The New Jersey Division of Investment announced a proposed $50 million investment in Blackstone Capital Partners VI. The proposal was part of Grady's larger initiative to invest hundreds of millions of New Jersey pension dollars in Blackstone. New Jersey records show state money began moving into Blackstone Capital Partners VI in March of 2012.

According to financial documents released in May 2011 by the Wyoming State Treasurer's office, Cheyenne Capital committed to invest $2.69 million to the same Blackstone fund in 2011.

The same document shows Cheyenne has invested $16 million in Blackstone Capital Partners VI, a private equity fund in which New Jersey's pension system also has investments.

The website of Cheyenne Capital lists Grady as a managing director. Documents filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission also describe him as a partner in the firm. New Jersey financial disclosure forms list Grady as having a personal ownership stake in Cheyenne Capital Fund, which made the investment in Blackstone Capital Partners VI. The forms also say Grady currently earns compensation from the Cheyenne Capital Fund. Yet in the section of his financial disclosure forms asking officials to list “any direct or indirect interest...in any contract made or executed by a government,” Grady did not list Blackstone Capital Partners VI, despite Cheyenne and New Jersey's investments in that fund.

In other dealings, Grady has demonstrated an awareness of conflict-of-interest restrictions. In 2013 he recused himself from deliberations over proposed New Jersey investments in his old firm, the Carlyle Group. But State Investment Council records do not indicate that he recused himself from deliberations over New Jersey’s Blackstone investments, despite his private firm's stake in Blackstone.

Instead, State Investment Council records show that Grady himself made the formal motion to approve the Blackstone deal, and then voted for it along with most members of the council. Former State Investment Council member Jim Marketti told International Business Times he had no recollection of Grady disclosing his firm’s investment in Blackstone at the time Grady had the council vote on the Blackstone investments.

Gov. Christie recently suggested that Grady's State Investment Council plays no decision-making role in considerations of individual investments. “They don’t make the decisions on the individual things that we buy," Christie said at a press conference last week. "They set out categories of the way they want to see it done, and then professionals that we hire, both in the Department of Treasury and outside, have made those choices.”

In fact, state records document that the council explicitly voted to approve the Blackstone investment.

Whether and how Grady’s firm may have benefited from New Jersey’s investment in Blackstone is impossible to discern from the outside. A spokesperson for the New Jersey Department of Treasury, Christopher Santarelli, said neither Cheyenne nor the state pension system would "derive benefit from the other's investment in a Blackstone fund.” But he, too, did not reply to a request to release the text of the agreements at issue.

Documents that have emerged in investigations of other transactions involving an overlap of interests for public pension managers and their private investments suggest the potential pitfalls. A Blackstone Capital Partners VI document that surfaced in a 2012 Securities and Exchange Commission investigation of the Kentucky Retirement System includes provisions for the firm to give “more favorable” terms to certain fund investors over other fund investors.

“Those provisions mean that private equity insiders could be granted special advantages at the expense of other investors like New Jersey's pension fund,” said former SEC attorney Ted Siedle, who now conducts forensic pension investigations for groups representing retirees. “There’s no assurance of a level playing field for all investors. It is the opposite -- these contracts allow certain investors to profit at the expense of other investors. This is exactly why there’s a huge potential for a conflict of interest when a private investor’s firm is investing in the same fund that the investor is having a public pension fund invest in.”

Another Blackstone Capital Partners VI document from the SEC investigation lays out a way in which Grady could have been granted preferential treatment on his private investment: The document says “each investor admitted as a limited partner...will be required to commit a minimum of $20 million.” Blackstone says it reserves the right to waive those minimums in special circumstances. Wyoming documents show Grady’s firm was permitted to buy into Blackstone Capital Partners VI with a $2.69 million commitment -- an amount the document says represents the “total amount” of its investment.

Blackstone appears to have given Grady a break on its usual minimum investment requirements; the firm declined requests for explanation.

A Useful Bailout

For Grady, Blackstone has served as more than a useful investment vehicle: The fund's resources have been used to co-invest on a bailout deal with a firm on whose board he serves, according to federal filings.

In August 2012, Blackstone Capital Partners VI used money from its investors to finance a deal involving Knight Capital Group, according to SEC documents. Knight had notably suffered losses in the wake of news that a computer glitch in its electronic trading system had sent share prices plummeting on the New York Stock Exchange. The infusion of Blackstone money stopped the bleeding. Blackstone had been joined in its rescue of Knight by another firm, Stifel Financial, which later acquired a piece of Knight's trading and sales operations. Among the members of Stifel's board was Grady, according to corporate documents.

According to SEC documents, Grady also owns more than 10,000 shares of the company's stock, and N.J. financial disclosure forms show Grady is compensated for his position at Stifel.

In short, Blackstone Capital Partners VI applied its investors' money -- including funds from the New Jersey pension system -- to co-invest with Stifel, whose board included among its ranks the overseer of New Jersey's pension investments.

Santarelli, the New Jersey Treasury department spokesman, said Grady's State Investment Council would have no knowledge or influence over how Blackstone opted to invest the money in its fund. Yet a New Jersey investment official previously declared that state officials often influence the financial decisions of the private equity funds in which the state invests.

"We're a large player," said then-Division of Investment executive director Timothy Walsh, in a May 2011 interview with the Bergen Record. "We have impact." He told the newspaper that state pension officials sit on advisory boards for most of the private equity firms with which New Jersey invests, adding that New Jersey's pension system is better able to influence private equity firms' decisions than those of companies whose stock it owns.

The New Jersey state pension system listed 600,000 shares of Stifel in its portfolio in 2013, according to the New Jersey Department of Treasury's annual report. Stifel executives made $15,000 worth of contributions to the New Jersey Republican Party in 2011, according to campaign finance disclosures.

Assemblyman John Wisniewski, a Democrat who chairs the New Jersey legislature’s Select Committee on Investigation, called for a formal investigation into the Blackstone transactions.

“I’m deeply concerned that Mr. Grady had an unacceptable conflict of interest that he failed to disclose,” said Wisniewski. “The health of our pension system is of paramount concern not just to the former employees who are collecting pensions or current employees who hope to get their pensions, but also to the entire citizenry of New Jersey who bear an ultimate responsibility to pay those benefits. To find out that the people entrusted with faithfully administering that system are potentially self-dealing for their own benefit is troubling and should be investigated.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.