Community Policing Could Help Rebuild America's Broken Relationship With Police, Experts Say

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said Thursday that enhanced community policing efforts within the New York City Police Department will build the necessary relationships between community members and police to help prevent violent, racially charged events like the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown. But ushering in that kind of transition across the nation would require a massive cultural shift, and could take years of relationship-building that might not end up as effective as authorities hope, criminal justice experts said.

Community policing is a broad philosophy that promotes engagement between the police and the people they are policing. While each department tends to adopt its own methods for engagement, a consistent recommendation is to empower the public and offer them the resources they need to raise awareness of and eventually solve the problems facing their neighborhoods.

Christopher Vicino, assistant chief of police in Riverside, California, said that community policing has helped bring the city’s crime rates to an all-time low. “Violent crimes probably dropped 30 or 40 percent over a 30-year period. Community policing isn’t the only thing that’s done it, but it has definitely contributed,” he said.

Community policing programs like Neighborhood Watch have proved effective in reducing crime, according to the Department of Justice’s Office of Community Orientated Policing Services, or COPS office. Community engagement has also helped relieve stress on strained police departments and improved the overall satisfaction of many communities where it is implemented, according to the State University of New York, Binghamton.

Vicino emphasized it’s not just one program or another, however. It’s an everyday philosophy that he teaches his officers to implement in all aspects of their policing, he said.

“It’s not a program, it’s not hiring more cops. It’s a philosophy that pushes the police officer to solve neighborhood problems," he said. "We don’t tell you what your problems are; we ask you what your problems are… When I came up 30 years ago, that was not the case. We told people what their problems were. What we didn’t realize was that these people are the experts on their neighborhoods; they know the problems that need solving, not us.”

The philosophy was a core tenet of policing before the turn of the 20th century. A 1994 DOJ report on community policing traced it to Sir Robert Peel, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, who founded the Metropolitan Police Force in London in 1829. He established a number of principles it would abide by, among them: “The police are the public and the public are the police.”

These practices were changed as police departments shifted their organizational structure and became increasingly more professional in the early 20th century, the report said. The philosophy became popular again in the 1990s and is seeing another resurgence following the deaths of 18-year-old Brown, an unarmed black man killed by a white police officer in August in Ferguson, Missouri, and Garner, a Staten Island man who was choked to death by a handful of police during an arrest in July.

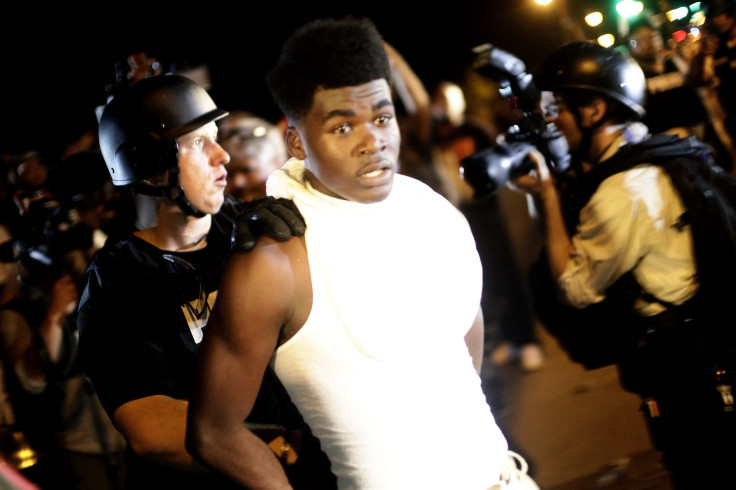

The officers involved in those deaths were not indicted by local grand juries. The cases reignited debate over how police interact with the public, and many protests turned into violent confrontations between community members and police.

“Listen, it's inevitable that someone is going to get hurt because of us,” Vicino said. “Some of these cops are 21-year-old kids with just six months of training and now have guns and batons, but the best thing that can happen in a situation like that, if people trust [the police], they'll wait for an investigation before they burn the place down. When you admit you're wrong when you're wrong and have some transparency, you won't undergo some of the terrible things going on around the country right now.”

The overall consensus among experts is community policing helps reduce crime and tension when properly implemented, said Edward Maguire, a criminology professor at American University in Washington, D.C., who edited a 2009 report on community policing strategies at 12 agencies across the country for the COPS office.

“Do we treat people fairly? Do we give them a voice? That principle is really at the core of community policing,” Maguire said. “If the authority figure is acting boorish or unprofessional, there’s a higher likelihood that situation will end badly and ultimately lead to more rebellion against the police.”

But it’s a complicated transition and requires a lot of commitment, resources and co-operation with the community, he said. Community policing methods aren’t always well-received by police unions, either.

In Green Bay, Wisconsin, where the department created positions for dedicated “community policing officers” (CPOs) and brought in civilians to department administrative positions, Police Chief James Lewis faced 42 court challenges over what local unions saw as a violation of their contract with the department. He ended up winning 41 of those cases. Some officers expressed frustration that the CPOs were not carrying their share of the workload, because they didn’t have to respond to 911 calls.

In Lowell, Massachusetts, as crime rates went down with the implementation of community policing, so did community engagement. The researchers in charge of the Lowell study found it was possible that all the community involvement led to more opportunities for disagreement among the involved public.

“I think there’s also some people who view it as being soft on crime,” said Maguire. “The reality of policing is that at some point you have to use physical force. I think there are some people who are a little more quick to go to physical force, but taking soft steps are really, really important to maintain a relationship with the community.”

In some ways, police departments have gone in the opposite direction by becoming increasingly militarized, especially following the 9/11 attacks and the Boston Marathon bombings. The Pentagon has transferred nearly half a million pieces of excess military equipment to American police departments since 1997, according to Bloomberg.

Lynda Leventis-Wells, executive director of the Carolina Institute for Community Policing in South Carolina, said she’s noticed that some police training programs have shifted to treating recruits like they are in the military, which she said translates into future officers treating their community members the same way.

“There’s a place for military philosophy, and that’s in the military,” she said. “Demilitarize the police, do whatever you have to do, but make sure you put money into training so we can teach these officers properly.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.