Complex Brain Evolution In Vertebrates Likely Began With Two Simple Parts, Not Three

The current conventional understanding of brain evolution among vertebrates proposes that current complex brains evolved from simple three-part brains comprising of a forebrain, a midbrain and a hindbrain. But an examination of a recently found marine species that has been around for hundreds of millions of years challenges that view, and suggests vertebrate brain evolution began with two parts, not three.

An international team of researchers analyzed the amphioxus, also known as lancelet — a living fossil, of sorts, that was long considered to be a faceless and brainless fish. Lancelets, which are not really fish, split from vertebrates about 520 million years ago, but their genome provides clues about the evolution of vertebrates. They are thought to be one of the first animals to have evolved a structure called the notochord, similar to the backbone seen in vertebrates.

Read: Big Brains In Primates Are Linked To Diet, Not Sociability

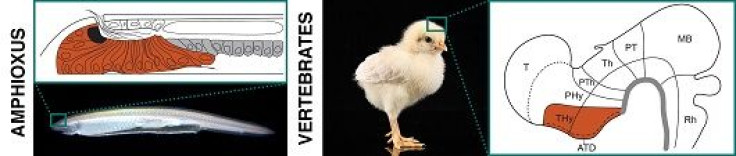

The researchers found the chordate species has, in fact, a complex brain, and they compared its development with how the brain evolved in vertebrates like chicks and fish. The comparison revealed that the thalamus, pretectum, and midbrain regions now found in vertebrates correspond to a single region in the lancelet brain, suggesting a common evolutionary and developmental origin.

Ildiko Somorjai of the School of Biology at the University of St. Andrews, United Kingdom, and a co-author of a study on subject, said in a statement Wednesday: “Amphioxus is an amazing creature that can tell us a lot about how we have evolved. Humans have enormous brains with a large number of anatomical subdivisions to allow processing of complex information from the environment, as well as behavioral and motor control and language. Research in amphioxus tells us that even an outwardly simple brain may have complex regionalization.”

Of the about three dozen or so species of lancelet that exist, the one examined by the study’s authors was found during a marine survey off the coast of Scotland in 2011. Other than a primitive back bone-type structure, lancelet has no clearly defined face, no bones or jaws, and its small brain has only a single “frontal-eye” that can sense light. Because of how little it has changed in the last hundreds of millions of years, the species has often been called a “living fossil.”

Commenting on possible applications of this finding, Somorjai said: “It also strengthens the position of amphioxus as an important non-vertebrate model for understanding vertebrate evolution and development, with clear implications for biomedical research.”

Other than St. Andrews, researchers who contributed to the open-access study came from the universities of Barcelona and Murcia in Spain, as well as the Center of Genomic Regulation, which is also in Barcelona. The research appeared in the journal PLOS ONE under the title “Molecular regionalization of the developing amphioxus neural tube challenges major partitions of the vertebrate brain.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.