Confederate Flag Debate: Mississippi, The Stars And Bars And Its Place On The State Flag

JACKSON, Mississippi — Off Interstate 55, in a slice of town surrounded by warehouses and shopping plazas, a little flag shop inside an old car dealership has a big piece of news. In the run-up to the Fourth of July weekend, "Old Glory" isn't the best-seller.

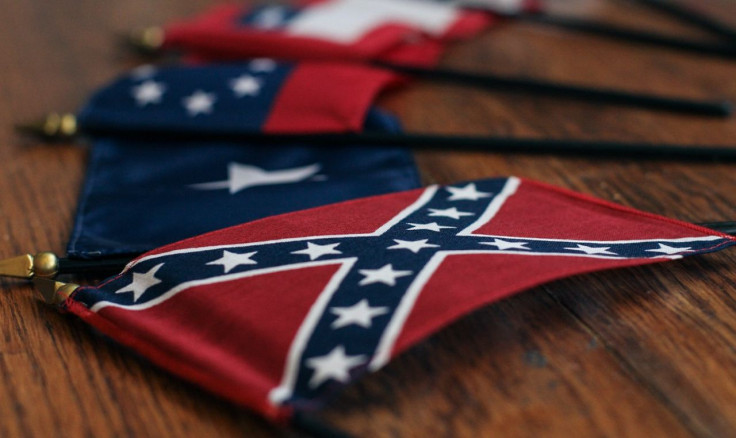

The American flag has given way to two new sales champions — flags that are also red, white, blue and shimmer with gleaming white stars: the Confederate battle flag and the Mississippi state flag. In fact, Brenda McIntyre's shop, A Complete Flag Source, is sold out.

"People are concerned they won't be available anymore," McIntyre said earlier this week. And there is good reason for that.

The Confederate battle flag is under intense scrutiny in Mississippi and across the U.S. in the weeks since the attacks on a historically black church in Charleston, South Carolina. On June 17, a gunman killed nine members of the Emanuel African Episcopal Church during a prayer service. The accused killer, Dylann Roof, appeared in earlier photographs waving a pistol in one hand and the Confederate flag in the other.

For decades in Mississippi opponents have tried unsuccessfully to strip the Confederate stars-and-bars from the state flag, which flies over government buildings, schools, town centers and in just about every public space. Critics say the Confederate battle flag symbolizes some of the ugliest eras in U.S. history: The enslavement of black people; the terror of white supremacists including the Ku Klux Klan; and the century-long effort by southern states to deny black citizens their equal rights.

As the Charleston shootings cast a glaring spotlight on the flag, some Mississippians say they believe a change may finally be afoot, either through a public vote or state legislation.

Opponents acknowledge that changing Mississippi's flag won't resolve broader problems of racial inequality, but they argue it's a necessary step for the state.

"A new flag will stand for a new Mississippi, and what we'll stand for going forward," said Hillman Frazier, a Democratic state senator in Jackson, on the sidelines of a recent anti-flag rally at the state Capitol. Music thumped from speakers near the concrete steps as a few dozen participants sought relief in the shade from the scorching sun.

"Stand up!" the event's emcee called out.

"Take it down!" the crowd shouted back.

"We recognize history. We had no control of our history. We can put part of our history in books and museums, where we can learn from it," Frazier said. "But in terms of flaunting it in public places, it's not appropriate at this point. You have to come up with a symbol that everybody can get behind."

'A Point Of Offense'

The Confederate battle flag — with its blue St. Andrew's cross, white stars and red backdrop — was one of several banners flown by Confederate Army soldiers during the Civil War from 1861 to 1865. It wasn't the official flag of the Confederate States of America, but several army units flew the battle flag during the war, most notably Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Mississippi added the emblem to its state flag in 1894, and the state is the only former Confederacy member to still include the stars-and-bars in its flag.

In recent weeks, a handful of Mississippi legislators have made the unusual move of speaking out against the state banner. Mississippi House Speaker Phillip Gunn on June 22 became the state's first Republican legislator to call for removing the Confederate emblem.

"As a Christian, I believe our state's flag has become a point of offense that needs to be removed," he said in a statement. State Sens. Thad Cochran and Roger Wicker said as much the same. Their calls arrived as governors in South Carolina, Alabama and Virginia similarly pushed to remove Confederate battle flags from state capitols and license plates.

But plenty of Mississippians, most of them white, say they see no reason to change the state flag. They recognize that people associate the Confederate symbol with slavery and racial injustice, but they argue the banner is, in reality, little more than a piece of cloth that was used during a historic rebellion. "A flag stands for something. It doesn't cause something to happen," as McIntyre, the flag store owner, puts it.

"It's utterly ridiculous what they're trying to do," said Dustin Peden, who was trying to buy the Confederate flag at McIntyre's shop.

Twenty miles northwest of Jackson, and over cups of sweet tea in Flora, his hometown of 2,000 people, Peden said this rural region of wide grassy fields and grazing cattle is chockfull of Confederate flag supporters. "As far as people saying, 'Hey, the Confederate flag is racist and hatred, and the Mississippi flag is hatred,' that's completely wrong," Peden said.

The 19-year-old, who is white, says he's itching to buy a Confederate flag so he can express opposition to the new flag movement. He plans to fly it along with the U.S. flag in the back of his black Toyota pick-up truck. The truck's got a duck hunting decal plastered on the back window and a Bud Light tap handle in place of the gear stick, and he says he expects his doors might get kicked in when he flies the Confederate flag in Jackson. But that's price he's willing to pay to express his support, he said.

"People in the South fight for what they believe in. And that's kind of the way I feel about the flag. We should fight to keep it," Peden said. "It's not just something we should sweep under the rug. So that's why I believe it's important to show my pride and history and fly it high on my truck."

Beyond The Battlefield

Many black Mississippians, however, don't share Peden's feelings for the flag. Kendall Patterson said he doesn't feel any pride when he looks at the Mississippi state flag and its Confederate emblem. He works as graphic designer in a state government agency, and he said he feels "indifferent" when saluting the U.S. flag at state functions, because the Mississippi banner is always right beside it.

"The people who want to hold onto it, they constantly want to brag that it's their heritage. But their heritage is insulting to me," he said. "Because my heritage is people who were owned by other people. That is the extreme worst thing that you can do, is try to own another human being."

Patterson spoke outside his friend's music and comic book store in Jackson's Millsaps art district, a tiny, predominantly black neighborhood squeezed between the railroad tracks and blocks of low-slung houses and auto repair shops.

Patterson, 35, said one of his earliest memories of the Confederate battle flag is from when he was 12 years old. He was playing with friends near the cemetery in his hometown of Natchez, about 90 miles southwest of Jackson on the Mississippi River. Local Ku Klux Klan members, who were burying a friend, stood over a grave site dressed in white hoods and waving the battle flag. The two groups locked eyes, and the boys ran.

"It's a symbol of hate and bigotry and racism," Patterson said of the flag. "It's a reminder of those times [of slavery]."

The debate around the Confederate battle flag stems from a broader disagreement about the Civil War's origins. The flag's supporters tend to say the bloody war was strictly about states' rights — with the South defending a confederation of sovereign states, and the northern Union troops fighting for a centralized federal government.

But Mississippi and other southern states clearly cited slavery as a reason to secede from the Union. Northern states, which had permitted slavery for more than a century, largely abolished the practice by the 1850s, and Southern leaders feared they could be forced to "submit to the mandates of abolition," which would destroy their agricultural economies, the state of Mississippi said in its 1861 declaration of secession.

"Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world," the document says. "A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization."

After the Civil War, the Confederate battle flag was flown mostly during memorials held by the families of veterans. It wasn't until the mid-20th century that it emerged as a ubiquitous symbol of Southern pride.

Strom Thurmond, a long-serving South Carolina politician, helped popularize the flag during his 1948 campaign for the U.S. presidency. His party, the newly formed States Rights Democratic Party, or Dixiecrats, promised to uphold "the segregation of races." Thurmond's supporters showed up to campaign stops waving the U.S. and Confederate flags. Around the same time, the Ku Klux Klan took up the Confederate banner when they unleashed violence on African-Americans and white civil rights supporters.

A Change Of Heart?

Past attempts to strip the Confederacy from the Mississippi state flag have been met with fierce opposition or general apathy. When the issue came to a vote in 2001, Mississippians voted by a 2-to-1 margin to uphold the current flag, in part because they didn't like the proposed alternative.

Proponents of a new state flag say they're hopeful the next time around could be different.

"More people are open to listening to other points of view. I think Mississippi is liberalizing in ways — not in a bad way, it just means change," said James Bowley, a professor of religious studies at Millsaps College, at the recent anti-flag rally in Jackson. "Younger generations grow up and think differently."

Phillip Rollins, who owns the Off Beat music store, said he wasn't old enough to vote during the 2001 initiative. Now he's 30, and says he's eager to have a chance to vote against the state flag. "I didn't want it then, and I still don't want it now," he says outside his shop, a red brick, glass-paned warehouse that used to house a printing press.

"I don't have a problem with people flying it on their property, or displaying it on their cars. That's all up to them," he adds. "But as far as [the flag] representing myself as a Mississippian, I feel that it’s a misrepresentation."

He and other opponents say they worry the state flag sends a message of exclusion and backwards thinking to businesses and people from outside Mississippi. "As soon as people see that when they come in the airport, it's like, 'Oh, this is what they're about here,'" Rollins said.

Wal-Mart, Sears/Kmart, eBay, Amazon, Etsy and Google Shopping in past weeks have all denounced the Confederate battle flag and said they'll no longer sell it in stores. Aunjanue Ellis, an actress and native Mississippian who starred in the movies "The Help" and "Ray," says she's moving her production company from Mississippi to Louisiana -- and she won't bring it back until Mississippi changes its flag.

"Mississippi suffers from brain flight, from economic flight, every day. And it's because people do not feel comfortable living here. It's stifling," she told reporters at the state capitol before the June 29 rally. "We are asking for empathy."

Confederate Stronghold

Despite cautious optimism that hearts are changing, George Flaggs, Jr., the mayor of Vicksburg, says he still doesn't think the state flag would ever change if left to a vote.

"Because you get to vote in secret. And when people have an opportunity to hide behind their true conviction, they may do that," he said from his office in the historic city hall.

Vicksburg, about 40 miles west of Jackson, is home to one of the Confederacy's most important battlegrounds. Seated on the muddy brown waters of the Mississippi River, the town was under siege in 1865 for 47 days, until Confederate troops surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant's Union army on July 4. The timing is a sore spot for some Vicksburg residents; the town didn't formally celebrate the Fourth of July until half a century after the war.

The city remains a hotbed of Confederate history and culture. At the Old Courthouse Museum, a grandiose 160-year-old building, Confederate currency, uniforms, documents and bullets fill rooms of glass display cases. Upstairs is a large memorial to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America. Tourists drift in through the heavy doors, usually after stopping by the Vicksburg National Military Park, a 1,800-acre memorial replete with trenches, monuments and reconstructed forts. Leaving the museum, some visitors buy replicas of the Confederate battle flag from the gift shop.

Gordon Cotton, a 79-year-old historian and the museum's curator, says he feels the battle flag has been unfairly vilified. After all, he says, it was the U.S. flag that hung from the bows of transatlantic slave ships in the 18th century. "The Confederate battle flag is part of our history, just like the U.S. flag is part of our history," he says from inside the musty museum. About the state flag, he adds, "People should focus on something more important."

Yet even in a city blanketed with reminders of the past, there's progress, Flaggs said.

"I'm sitting here as an African-American male in the city that the war ended on. It speaks for itself," he said behind his wide wood desk. Flaggs served as a state representative from Vicksburg from 1988 until 2013, and he says the number of black policymakers has doubled from when he first took office.

But the Confederate battle flag and its prominence on the state flag continues to breed a culture of tension and bigotry, he says. He's hopeful policymakers will seize the moment sparked by the tragedy in South Carolina and adopt an alternative for Mississippi.

"It's unfortunate that Charleston put this much light on it, but it happened. And because it happened, it needs to change the minds of the people and the legislature in this state," the Vicksburg mayor said. "People now are speaking like never before, because they can feel the time has come."

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.