Debt Ceiling 2013: A Timeline Of Fights Over The U.S. Debt Limit Since 1917

About now, many Americans wish they had never heard the term debt ceiling -- or knew so much about what it meant. But with lawmakers hesitant to approve an increase in the amount that the U.S. government is authorized to pay for debts already incurred by Congress, this phrase has become a household word, as it were. Although it feels like this latest gridlock between Congress and President Barack Obama is yet another indication of today’s steely partisan politics, debt-ceiling conflicts have been to one degree or another Washington staples for the past four decades. Before the 1970s, not so much.

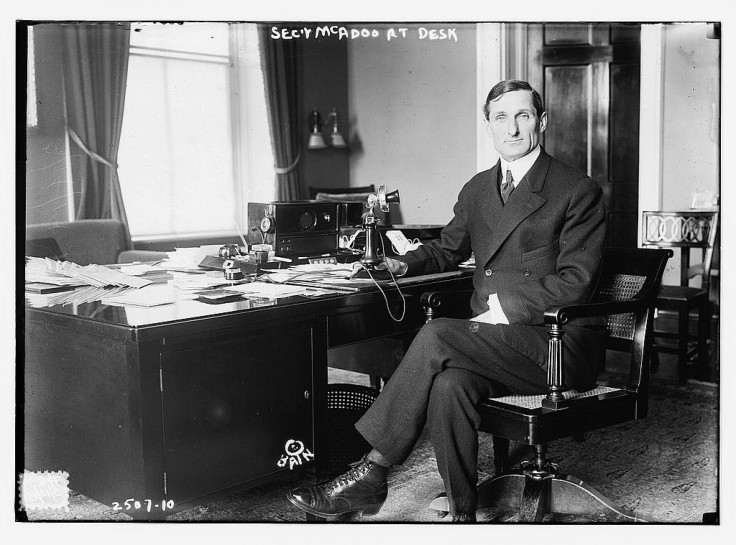

The first time the debt ceiling came into view was in 1917 with the adoption of the Second Liberty Bond Act, which placed limits on expenditures for large categories of debt such as bonds and bills. Before then, Congress had to authorize loans and other debt instruments individually. In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress to remove the $30 billion ceiling on Treasury bonds. And soon afterward, Congress eliminated individual limits for specific types of debt, leaving only one aggregate ceiling for the government’s total indebtedness. This gave the Treasury Department more flexibility in determining the types of instruments it issued.

Between 1941 and 1945, federal debt skyrocketed because of World War II, from $49 billion the former year to $268 billion the latter year. The federal debt limit rose accordingly during that time as well, reaching a peak of $300 billion. When the war ended, Congress actually voted to lower the debt ceiling to $275 billion.

But conflicts over the debt ceiling and federal budget were generally small in scale until the 1970s when President Richard Nixon angered Congress by adopting a strategy known as impoundment, designed to allow him to decide line item by line item whether to release Congressionally appropriated funds. While Nixon claimed he needed this power to reduce the deficit, he was criticized for using it to block initiatives he didn’t agree with. After Nixon refused to disburse almost $12 billion in funding, Congress retaliated with the passage of the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act, which created the Congressional Budget Office and nullified the president’s ability to use impoundment.

From the 1980s onward, the federal budget and debt rose significantly. In 1981, Congress passed a $1 trillion debt ceiling, which so vexed Sen. William Proxmire that the government-waste critic and Wisconsin Democrat staged a 16-hour filibuster in an attempt to pass a lower spending-limit bill. By the end of the ’80s, the federal debt had risen to $2.8 trillion.

As for federal shutdowns, they were few and far between. In 1995, however, the Republican-controlled Congress and President Bill Clinton found themselves at loggerheads over spending for Medicare, public health, the environment and education. During this conflict, Congress refused to fund the government for days on end in November and December.

Fast forward to October 2013. Congress failed to pass a bill this month to fund continuing budgetary activities, shutting down much of the government as a result. Currently at $16.7 trillion, the debt ceiling will have to be raised by Oct. 17, and lawmakers are balking about that as well.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.