Do Black Holes Really Have Event Horizons? Einstein’s General Theory Of Relativity Passes Another Test

It is common understanding that all black holes have event horizons — the point beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape the gravitational pull exerted by the densest known objects in the universe. But not all theorists agree that such a phenomenon — the event horizon — exists; they argue instead for something far stranger that is based on modifications made to Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity.

According to the widely accepted theory of black holes, based on Einstein’s relativity theory, black holes, including their supermassive variants, form when a star with a mass approximately great than 20 suns, collapses onto itself after running out of energy to support itself. The resulting dense concentration of matter has gravity so strong that it accretes everything that comes within its gravitational sphere, growing in mass all the time. Since everything includes light, a black hole is not directly visible, earning it its name. The concept of event horizons, while accepted by a large number of people, has not yet been proven, however.

Read: Astronomers Are Pursuing A Runaway Supermassive Black Hole

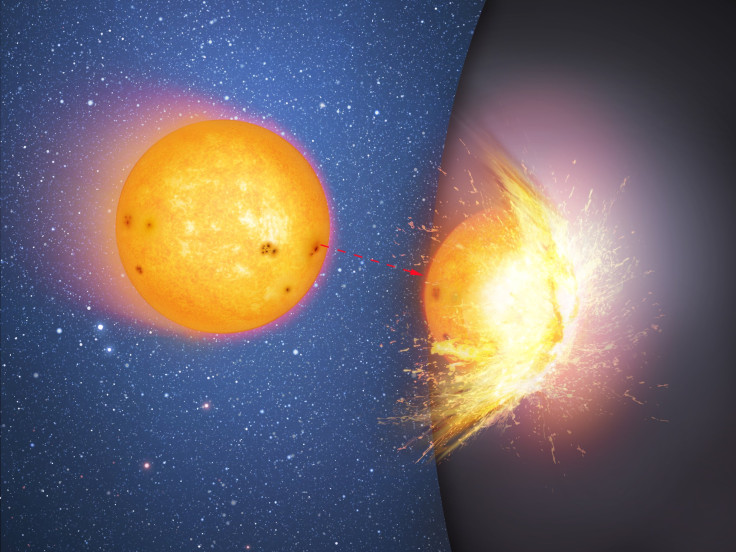

Some scientists who are from the naysayers camp suggest that instead of supermassive black holes at the centers of most galaxies, there sit objects that somehow managed to not collapse into a singularity, and therefore have no event horizons. In the absence of a singularity, these theoretical objects would have a hard surface, and objects that get pulled to it would hit the surface and be destroyed.

Pawan Kumar, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Texas, Austin, his graduate student Wenbin Lu, and Ramesh Narayan from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics at Harvard University, devised an experiment to determine which of the two theories was correct.

“Our whole point here is to turn this idea of an event horizon into an experimental science, and find out if event horizons really do exist or not. Our motive is not so much to establish that there is a hard surface,” Kumar said in a statement Tuesday, “but to push the boundary of knowledge and find concrete evidence that really, there is an event horizon around black holes.”

If a star hit the hard surface of the supermassive object and get destroyed, its gas would envelope the object and be visible to telescopes for a long time, many months or even years. Once the team figured that out, the researchers estimated the rate at which stars fall into supermassive black holes, considering only the really massive ones with about 100 million solar masses.

Then, using data from a recently completed survey of half the northern hemisphere sky, collected by the 1.8-meter Pan-STARRS telescope in Hawaii over a period of 3.5 years, they scanned for “transients” — the name given to objects that glow for a while and then fade. The intent was to find transients with the same light signature as expected from a star hitting a hard surface.

“Given the rate of stars falling onto black holes and the number density of black holes in the nearby universe, we calculated how many such transients Pan-STARRS should have detected over a period of operation of 3.5 years. It turns out it should have detected more than 10 of them, if the hard-surface theory is true,” Lu said in the statement.

The researchers didn’t find a single transient matching their criteria.

Read: Earth-Size Event Horizon Telescope Starts Operation

To improve their test, the researchers now plan to use data from a larger telescope — the under-construction 8.4-meter Large Synoptic Survey Telescope in Chile. Once complete, that telescope would offer far greater sensitivity than Pan-STARRS.

“Our work implies that some, and perhaps all, black holes have event horizons and that material really does disappear from the observable universe when pulled into these exotic objects, as we’ve expected for decades. General Relativity has passed another critical test,” Narayan said in the statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.