Ebola Panic The New Normal As Outbreak Spreads, Death Count Rises

Everyone seems to think that everyone else has Ebola. With the virus spreading to Europe and the U.S. after months of a deadly outbreak in West Africa, a state of irrational fear that the person sneezing next to you on the bus could be spreading the deadly hemorrhagic fever has become the new normal.

As overblown as it may be, the Ebola panic sweeping the globe will likely only get worse as the epidemic continues well into the winter flu season. Every case of the sniffles or food poisoning could be met with a heightened level of alarm, and some health workers say that emergency rooms are already seeing patients increasingly worried that they may have Ebola.

"I have seen several people who had acute illnesses worried that they may have Ebola," though they had not traveled to West Africa or been in contact with known Ebola patients, Dr. Mark Reiter, a Tennessee emergency room doctor and president of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, told CNN last week. "But it has gotten a tremendous amount of media coverage, and some people are especially concerned about it, even if it is highly unlikely."

A Pew study of 1,007 American adults conducted between Oct. 2 and Oct. 5 showed that 32 percent of adults are either “very” or “somewhat” worried that they or someone in their family will be exposed to the Ebola virus. And research shows that emergency rooms become more crowded when a global health scare figures prominently in the media. A 2010 study found that emergency room traffic jumped 7 percent when swine flu was a major news story, according to CNN.

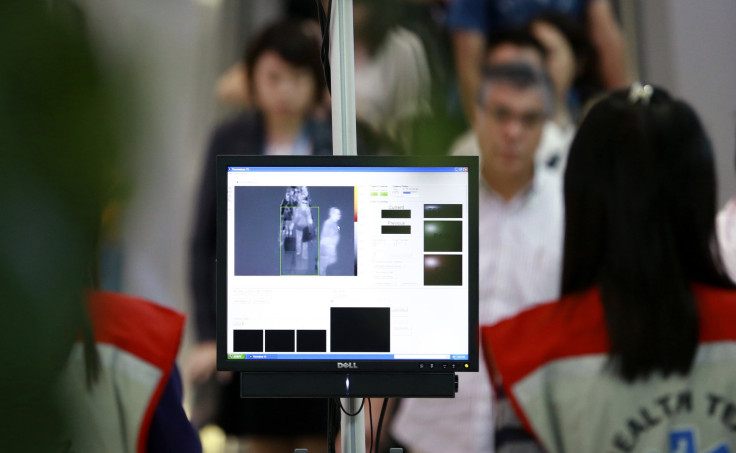

“Holiday travel should be especially interesting this year,” Reddit user i_run_far wrote on the popular online forum last week. The sentiment succinctly sums up the public mood at a time when health care workers in bright-colored protective cover-all suits are quarantining people with headaches on planes and travelers are checked for fevers at airports as part of an effort to stop Ebola’s spread.

The World Health Organization has assured people that the deadly disease is not airborne following recent speculation. A spokesperson said: "Following recent media reports, the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response seeks to clarify that Ebola is not an airborne disease. At this point in time we have no evidence and do not anticipate that the Ebola virus is mutating to become airborne. However, there are real risks and concerns with this outbreak: every day more people are becoming infected and more are dying because they cannot get the care they need. Energy needs to be focused on swiftly addressing the real needs and gaps in communities affected by this disease."

When Liberian Thomas Eric Duncan was diagnosed with the disease in Dallas after returning from a trip to Liberia last month, many Americans reacted with anger at the man who went on to become the first person to die of Ebola in the U.S. for not being sufficiently concerned about his potential for spreading the disease.

A nurse who treated Duncan for Ebola in Dallas tested positive for the virus herself on Sunday, despite the fact that she always wore the gown, gloves, mask and shield recommended for protection from the disease when she was with him, the New York Times reported. The revelation suggests that Ebola isn’t quite as difficult to spread as health authorities have said.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Tom Frieden said Monday that the Dallas nurse's infection is a game changer that will “substantially” impact the way public health officials approach the virus going forward. "We have to rethink how we address Ebola control, because even a single infection is unacceptable," he said, according to Politico.

The uncertainty surrounding Ebola has led to discord even among nurses, doctors and sanitation professionals working in the trenches of the outbreak and places where fears are high that it could be contracted. Workers have gone on strike or quit their jobs to avoid potential exposure to the virus in settings as varied as Liberian health care facilities, New York’s LaGuardia Airport and a Madrid hospital that saw Ebola spread from a patient to a nurse.

As the death toll of the worst Ebola outbreak in world history continues its climb past 4,000 bodies in seven countries, there is little certainty about what the future will hold for the epidemic. But it seems clear that fear, paranoia and panic will remain until the outbreak is eradicated and a cough becomes just a cough once again.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.