Entrepreneurs In The Middle East: Where And How To Invest In Startups In The Arab World -- Author Q&A

Author-investor Christopher Schroeder bucks contemporary wisdom about the Middle East by seeing positive economic prospects for a region that has experienced two and a half years of popular -- and often violent -- tumult. In 2010, Schroeder was among the first to predict the tumult in a Washington Post op-ed about startups in the Arab world. After working in e-commerce and with Silicon Valley venture-capital funds, Schroeder was invited by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s office to judge a startup competition in Cairo one week before the revolt in Tahrir Square.

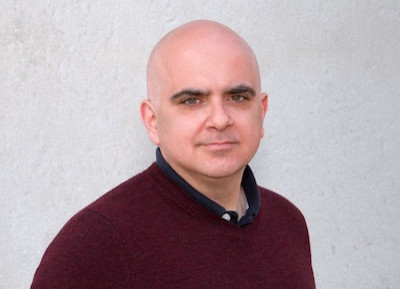

Schroeder, who lives in Washington, D.C., sat down with IBTimes’ Alan Edelstein to talk about the Arab Spring, female entrepreneurs, Florence during the Renaissance, the inevitable power of technology, and his recently published book "Startup Rising: The Entrepreneurial Revolution Remaking the Middle East." (Palgrave Macmillan).

IBT: Have the events of the recent past, like the crackdown in Tahrir Square in Cairo, put a dent in your sense of optimism?

Christopher Schroeder: The story is still being written [about] what the young people have been doing both politically and with entrepreneurship in Egypt right now. Regardless of where they were on the spectrum, they were worried about whether the Muslim Brotherhood was going to be addressing a lot of the basic economic concerns. I think there was a lot of general worry about that. And then there was this brief, almost euphoria, that there’d be something different when the, whatever we call it -- coup -- happened this summer. And then a few days later when there was shooting -- and I know two entrepreneurs who were killed in that period; there’s no question that it had a chilling effect on what does this really mean on a going-forward basis. And then we went through this cycle where things seemed to get peaceful, young people just put their heads down, were able to transact business, were starting to get hopeful again. …

Emerging markets are not for the faint of heart, right? There are challenges in China, challenges in India, challenges in Brazil. Political stability is a big issue, the rule of law is a big issue, and yet this new generation -- not just in the Middle East but in all these emerging-growth markets, continues to build. … I don’t know how Egypt will play out in the next three years but I have 100 percent certainty that a lot more people are going to have a lot more technology in their hands.

IBT: You were a young adult at the time of the Tiananmen Square revolt in China. Are there similarities?

CS: At that time I was working at Secretary [James] Baker’s office at State, and … the three “conventional wisdoms” of the world that were almost undebatable were that Japan was going to win it all; that China after Tiananmen Square could not be [economically successful] -- remember that in both the business community and the policy community you could not have significant economic growth if you did not have Jeffersonian-like political liberalism; and nobody thought much of India -- we forget now that around this time India was having terrible riots, thousands of people were injured and killed. Yet within five years of that time, of course, all the three premises that I just said were immutable were no longer being said by anybody.

It’s instructive about the kind of narratives that we have … I think it’s also instructive because while China has obviously been this amazing juggernaut, despite those predictions, they still have such unbelievable transparency issues and contractual rule of law issues … Twenty years of investors finding ways to become comfortable with political risk in emerging-growth markets like the Middle East and Africa can happen with greater efficacy now because [we have so much more] experience in having navigated it.

IBT: Westerners often think of the Middle East in monolithic terms, as a place of unrelieved chaos and unrest. From an investor’s perspective, where do you see the most promise in the region?

CS: My first answer, which is a more macro and not a purely investor answer, is that where there is ubiquitous access to technology we’re seeing really interesting innovation and absolutely fundable companies. Having said that, geography is not irrelevant … If you’re having to look in the short-term, geographically there’s no question that Amman [Jordan] is a really interesting place to look -- which is not surprising as it’s been attracting some outside capital as well as regional capital -- and the Emirates. I think one of the challenges of a place like Dubai for entrepreneurs in particular, is [not] just that it’s an expensive cost of living place, but in terms of the free flow of goods and ideas. Both the Emirates and Jordan have passed some chilling Internet protection laws, but even in the face of some of that there’s no question people are pushing really, really interesting ideas there, from an economic perspective and from an innovation perspective.

As a pure market, by the way, and particularly in the area of e-commerce, Saudi Arabia is a very interesting place, and most of the e-commerce people are looking for ways to have partnerships and reach markets there. But the government restrictions, and certainly the restrictions on 50 percent of the humans there, is something that, as an investor, I would not look as directly as I would as Dubai and Jordan.

IBT: Let’s talk about that “50 percent of humans.” You say that despite tradition and government restrictions, women have a strong entrepreneurial presence throughout the Middle East.

CS: It surprises Westerners no end and it surprised me no end the first time I went there, that such a large proportion of the people I would see at Internet gatherings and pitching business in the Middle East were women.

We’re in the early stages of getting good data, but I can anecdotally confirm what the Economist wrote this summer, which is that as much as a third or more of the tech entrepreneurs are women. And it doesn’t surprise me given what I’d seen.

So what’s going on? How do you square that in a region where, like in Saudi Arabia, women aren’t allowed to drive and so on? It was very interesting when I reported this out. I asked a lot of women this story and I got two very distinct reactions. I had an amazing number of women who … effectively said, “Do not call me a woman entrepreneur, I am so tired of you Americans trying to bucket this thing. Yeah, there are challenges here [but] there are challenges everywhere. This is not about bad men, this is about building great companies and I’m happy to talk to you about my company -- let’s do that.” They really sort of cut me off at the knees about that question.

And then of course there were lots of women that I talked to that said, “Let’s be real: I want to build an e-commerce platform, I want to go to Saudi Arabia, but I can’t drive there. Let’s be real, a lot of the venture capitalists here are men, they’re patronizing, they’re not treating me with the respect that they’d treat another person. I’m taking full-scale responsibility for my family; my parents don’t necessarily like what I’m doing because of that traditional view.”

So I think like most things in life, the truth lies somewhere in between. Almost every woman at some point said something to the effect of: “I’ve spent my whole life working around things. I’m as ready to be an entrepreneur as anyone. I spent my entire life having to execute and deliver, and people have doubted me. I just keep working around and finding solutions, I’m ready to go.” And I think there’s a lot of truth to that.

IBT: In terms of innovation, is there a “Silicon Valley of the Middle East,” or is it a more diffused kind of set up?

CS: Wherever I go in the world one of the most common questions I get is, “What is the Silicon Valley of ‘X?’” And I think that geographic hubs and ecosystems matter a lot. And for all of the hubris of Silicon Valley, it’s an extraordinary place. I think there’s only been one Silicon Valley in world history -- you could maybe say Florence during the Renaissance or something -- but I mean it’s an extraordinary thing, so I think to look for that, or replicate that per se is unrealistic.

The story of our time is in the diffusion of technology -- we’re going to be seeing a series of hubs and not necessarily one dominant hub that sort of takes it all. Young people want to be in great cities; it’s not a surprise that Sao Paolo has built an ecosystem and it’s not a surprise that Berlin is now building an ecosystem. I think the idea that one region is going to have one thing and that’s it, is not what I would predict.

IBT: You don’t shy away from addressing some fundamental cultural and religious issues concerning Islam and the Middle East. Is it your sense that the proliferation of technology and globalization has made the world a much smaller place, and that the cultures of the world are much more in each other’s faces than they used to be?

CS: I decided to go at it in the book because I think it’s so important, even though I risk going places where I have no expertise. One of the biggest reasons that I went at it is that I do think that the narrative in our country about Islam and religion is based on a very narrow understanding, framed quite powerfully by September 11 and the terrorists we see on the news all the time. So, I could return from Indonesia, which is the largest Muslim country on Earth, and no one ever asks me about the role of Islam in the ecosystem there, right? I come back from Israel, obviously no one asks me about Judaism, I come back from India, nobody would ever ask me about Hinduism. I’ve never met a Silicon Valley person to invest in this country or raise religion no matter who is in front of her or him in that area. And yet when I return from the Arab world it really is the first question I get invariably because of this very strong narrative that we have both experientially and because it’s confirmed by the media.

I found in my reporting it’s a much more nuanced thing, that the connections between individualism and many things that we hold dear in the States both politically and economically are completely in synch with Islam, that most of the young entrepreneurs I met were deeply faithful, but their faith was also highly individualistic; they didn’t feel they wanted to nor expected to follow anything hierarchically or lockstep. … I really do believe that there’s no going back, there will be more technology, not less, and I really do feel that the net positives unleashed by the tools available to problem-solve today that weren’t available even five years ago, will have a profoundly positive outcome … For good and for ill cultures are very deep, deep things, and there are values that come with them that are so unbelievably important to people that I can’t imagine that while technology allows us to see how the other guy lives, and it brings some homogeneity in terms of music, and art, and seeing how other people live … people use the technology in order to do really powerful things with their culture. Not only do I think it’s possible, I don’t think that there’s any choice.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.