European Refugee Crisis: Western Balkans Border Closing May Force Asylum-Seekers To Seek Other Routes

Along the Greek-Macedonian border for the past several months, people have been resting wherever they can -- leaning on fences, sleeping on piles of clothes, slumped in dirt or in the arms of their loved ones. Thousands of refugees and economic migrants on the Macedonia side of the border have continued to crowd near barbed-wire fences and live in makeshift shelters as authorities have attempted to entirely seal the popular crossing for asylum-seekers looking to walk through the Balkans to Northern Europe.

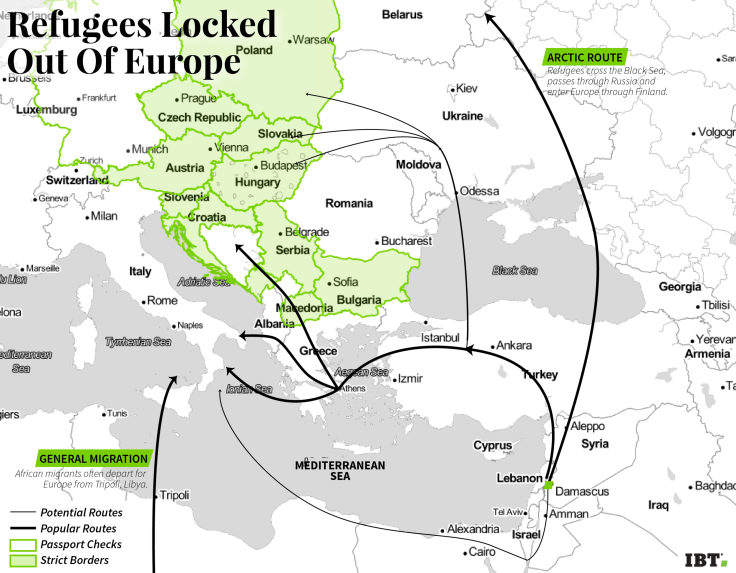

As European Union leaders met at a summit with Turkey Monday to discuss the ongoing refugee crisis in Europe, information leaked that the EU was planning an entire shutdown of the so-called Western Balkans route that begins in Macedonia at the border with Greece and extends up toward Austria. Route closures and border control have not deterred asylum-seekers from trying to cross in the past, and migration experts said this latest attempt to stem refugee arrivals would only push people to take more dangerous sea routes or to use smugglers.

“It is almost impossible to completely close the borders, so there will always be a way and paths where you can irregularly cross,” said Eugenio Ambrosi, the European director for the International Organization for Migration, a Swiss-based intergovernmental organization that looks to ensure migration takes place in a humane way. “The reasons that are pushing these people to come to Europe are too strong to be stopped just by a fence.”

More than 1 million asylum-seekers fled to Europe in 2015, and 2016 is projected to see equally high — if not higher — numbers. Nearly half of all refugees who have arrived are fleeing Syria's civil war, and the vast majority of all asylum-seekers are bona fide political refugees, according to the United Nations, which defines a refugees as persons who are fleeing a political regime or persecution for fear of losing their life.

Greece has been a popular point of entry for asylum-seekers because of its proximity to Turkey, and more than 800,000 of the 1 million arrivals in 2015 passed through Greece. The southern European nation serves as a transit point for most asylum-seekers, who look to resettle in Germany, Sweden or other northern European countries, frequently walking or using smugglers to pass through the Balkans. Since the refugee crisis reached a boiling point in the summer of 2015, Turkey has been both a main destination and transit country to Europe for many people coming from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. It has borders with Iraq and Syria in the East of the country.

But that route could now be cut off.

The meeting of European leaders in Brussels is an attempt to slow down the refugee crisis in Europe and bring normality back to the Schengen area, an area designated by a group of 26 European countries as a passport control-free travel zone for residents and visa-holders. While asylum-seekers do not fall into either category, they have traditionally been treated as an exceptional case and given free passage in Schengen. The Western Balkans route has been popular given that it is one of the safest ways for refugees to travel from Greece to Northern Europe, where a strong job market and German Chancellor Angela Merkel's outspoken welcome of refugees have attracted them.

Despite the leaked document of the proposed border closure stating in part that “Irregular flows of migrants along the Western Balkans route are coming to an end; this route is now closed,” Merkel and EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker argued that it is still open.

The two European leaders are attempting to change the wording of the so-called EU Commission Roadmap document, claiming the border is still open to Iraqi and Syrian refugees. Martin Schulz, president of the European Parliament, agreed with their stance. “I don’t believe that this is a summit in which doors will be closed. I hope that we can find a sensible and humanitarian solution for refugees who desperately need our protection,” Schulz told reporters in Brussels.

Turkey held up Monday’s negotiations by asking the EU for an additional $3.3 billion, doubling the aid it will get to take back hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees that Europe is not allowing to remain in the 28-country bloc. Ankara also asked for easier access to EU visas for Turks to enter Europe and an acceleration of Turkey's membership to the EU.

Since September last year, a spate of European countries within the Schengen area temporarily closed their borders or instituted passport controls. Additional countries outside of the Schengen area that border Greece also closed portions of their borders, which led to dramatic footage being transmitted across the world showing refugees from places like Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and other parts of Africa being squashed against razor wire fences and brutalized by security forces.

Asylum-seekers who have already arrived in Greece and find their access to the Balkans route closing could opt to make the mountainous border crossing through Albania and then take smugglers’ boats to Italy, which is around 140 kilometers (86 miles) from Albania across the Adriatic Sea. However, it could also push refugees into more dangerous trafficking conditions, according to Ambrosi of the International Organization for Migration.

“The condition of smuggling and trafficking will deteriorate in terms of higher costs, in terms of abuses, overall treatment and condition,” he said. “The harder it is to come across the border, the more costly the service from the smugglers will be.”

Refugees already pay as much as 2,000 euros per person, or around $2,200, for a seat on a crowded rubber boat from Turkey to Greece. The United Nations has also reported women being forced into exchanging sex for smuggler services if they run out of money. The conditions are already cramped and dangerous. An incident in Austria last August in which 71 people suffocated while being smuggled in the back of a truck brought to light the extreme conditions asylum-seekers are willing to submit to for a chance at finding a haven in Europe.

As asylum-seekers who are stranded along the Greece-Macedonia border plan their next move on their journey to Northern Europe, the conditions of refugee camps in Athens and the Greek islands risk becoming even more cramped, impeding access to food, healthcare and sanitation. In shelters run by the U.N. on mainland Greece, around 33,000 people are occupying spaces that were intended for 16,500, according to Katerina Kitidi, spokesperson for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Greece.

“When you have such a crowded situation there are a lot of tensions,” Kitidi said, adding, “What we need to do is establish more legal routes for people.”

It was not immediately clear what the final solution for the crisis will be or how negotiations in Brussels will pan out, but it appears that safer routes through the Western Balkans that are favored by refugees will be severely limited in the foreseeable future, forcing more people to take risks that could cost them their lives.

“Closing another route is akin to locking a door on a burning building,” said Iverna McGowan, head of the European Institutions Office and advocacy director at Amnesty International in Brussels. “People will jump out the windows, people will find another way.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.