At General Electric Company, Workers Struggle To Find Footing As Shareholders Reap Windfalls

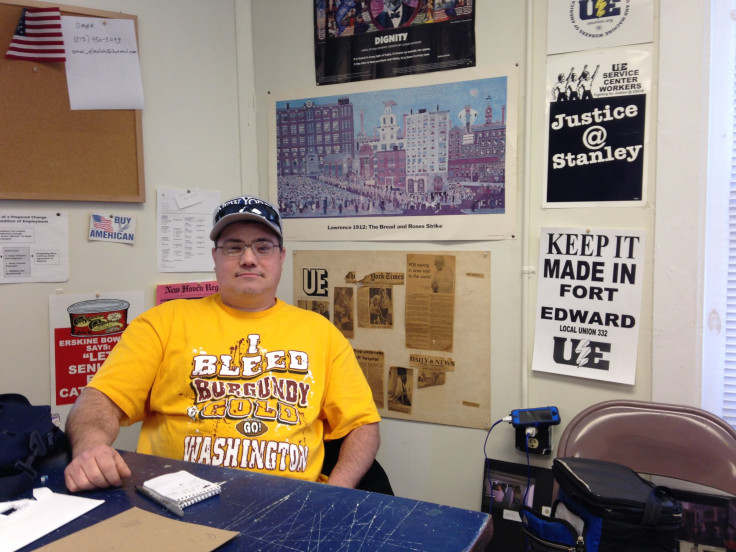

FORT EDWARD, N.Y. -- General Electric’s decision to close its capacitor plant in upstate New York came as a shock to Mark Rock, 43, a 10-year veteran on the assembly line.

“Honestly, I didn’t believe it because I’d heard it was closing since I was a kid,” says Rock, whose father also worked at the World War II-era plant and would regularly share his anxieties over job security with the family. “It’s turning my whole life upside down.”

That announcement, in September 2013, triggered a mandatory 60-day bargaining session with the union, but the savings targets proposed by GE amounted to a jaw-dropping hourly wage cut: from $28 to $11. When negotiators for the United Electrical Workers refused to budge, GE confirmed it was closing the 200-employee factory in Fort Edward and moving operations to the union-free shores of Clearwater, Florida.

When the new plant finally opens, full-time employees will earn around $12 an hour, with part-timers taking home $8, according to the union. (GE says it cannot confirm the wage figures for competitive reasons.)

The view is somewhat different if you’re an investor in GE. Charles Sizemore, principal of Sizemore Capital Management in Dallas, has seen the value of his holdings in GE increase 28 percent in the past two years.

Sizemore couldn’t be happier with the company’s capital allocations of late. At the same time that GE has cut back in Fort Edward, it has embarked on a major restructuring program and devoted tens of billions of dollars to dividend increases and stock buybacks.

Last week, GE announced a companywide shakeup that will jettison its financial arm and free up some $90 billion over several years. The majority of that cash, GE says, will be devoted to a series of buybacks and dividends concluding in 2018. The buyback plan, highlighted in the company's quarterly earnings report Friday and slated to deliver $50 billion to investors, ties Apple for the largest ever proposed.

"It took me by surprise," says Sizemore of the announcement. But he wasn't upset. GE's stock rose 11 percent on the news last Friday. "If they buy back their shares and are doing so at reasonable prices, then I’m all for it. I think it’s great."

Back in Fort Edward, the company still hasn’t announced a final closure date. But as the mill winds down operations, many workers are sticking around until the bitter end. As one of them, Paul Rosati, 50, puts it, “There’s not a lot of jobs in this area, and there’s really not a lot of jobs that pay anything close to what we’re making.”

Neither Rosati nor Rock are sure of their next steps. “You’ve invested 15 years of your life at this place,” Rosati says. “You’ve paid your dues, you’ve worked your third shift, your swing shift, you’ve accumulated your vacation time. And now, you have to start over at the bottom again.”

As workers at firms like GE grapple with changing fortunes, shareholders at major U.S. corporations have enjoyed near-record payouts. No company exemplifies the trend quite like GE. The same year that the company drove a gut-wrenching bargain in the upper Hudson Valley, the board of directors approved a plan to fork over $10 billion from company coffers to shareholders in stock buybacks.

As buybacks and dividends pad the portfolios of major investors, workers feel the squeeze. The Fort Edward factory is one of a few dozen domestic plants that GE has shuttered in recent years, casualties of what the company portrays as a response to ongoing international competition. While GE has opened some new domestic facilities, the company has eliminated 16,000 positions in the United States since 2008, according to annual financial reports.

“They’ve stopped investing in business,” says Sonny Gooden, 60, another Fort Edward worker.

Buyback Fever

Corporate America is in the midst of a buyback binge. Since 2009, S&P 500 companies have spent more than $2.5 trillion buying back their own stock. The $565 billion spent on buybacks in 2014 was the highest annual total since 2007, according to data from FactSet. February set a single-month record with more than $104 billion announced in share repurchases.

Companies repurchase their own stock to signal confidence that the firm’s share value will grow and concentrate shares in fewer hands. Like dividends, buybacks are generally beloved -- and sometimes demanded -- by investors, despite the implicit signal that the company is forgoing potential investments like research and development.

Driving the trend are record corporate cash holdings, now totaling around $1.4 trillion. “Companies are feeling flush with cash,” says Matt Coffina, editor of Morningstar StockInvestor. Combined with artificially low interest rates, which allow companies to finance buybacks cheaply, the conditions are ripe for booming shareholder rewards.

That immense cash flow has made buybacks a defining feature of the post-recession markets, helping buoy stock gains. Shareholders of top corporations welcome the development. An exchange-traded fund of companies active in buybacks has grown 45 percent in the past two years compared with the S&P 500's 34 percent.

Left Behind

But less than half of Americans actually own stock. Most people derive the bulk of their income from wages. And, on that front, the recovery has been considerably less kind. While jobs have returned, a stubbornly high share are concentrated in low-paying sectors like retail and fast food. From 2007 till 2014, hourly wages for the median worker fell 36 cents.

As shareholders have hit the post-recession fast lane, the working class sputters behind. The gap between the rate of stock market growth and wage growth is the largest in any bull market since 1966.

The nation’s largest employers have helped fuel the two-tiered recovery, keeping labor costs in check as they spend billions on buybacks. Since 2012, protesters have asked fast-food corporations to pay their workers $15 hourly wages, but to no avail. And yet, last year, McDonald’s bought back $3.2 billion in stock. Yum Brands, which owns KFC, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell, spent $820 million. In 2011, a labor-funded group that represents Walmart workers asked for $13 wages -- a figure that exceeds the company’s recent hike to $9 an hour. The retail giant, meanwhile, is on its way to a $15 billion buyback goal set by its board of directors in 2013.

Other companies have cut payrolls while putting billions back into the stock market. In October, just months after announcing 16,000 layoffs, Hewlett-Packard launched into a shareholder reward program that promises to return half of its available cash to investors through dividends and buybacks. The company will dole out an estimated $3 billion to investors in 2015.

In other cases, shareholders have won commitments as employee benefits have gone by the wayside. Months after delivery giant UPS announced a $2.7 billion buyback spree in 2013, it entered contract negotiations with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, which represents 250,000 company employees. At the bargaining table, Big Brown successfully fought demands to significantly boost pay for temporary workers and won increases in workers’ out-of-pocket healthcare costs.

“If the company could spend that $2.7 billion in protecting health care for workers and upgrading wages for part-time workers, that would be a tremendous home run for the labor force,” says Ken Paff, national organizer for Teamsters for a Democratic Union, a dissident labor group critical of the contract. “That’s an astronomical figure.”

Striking A Balance

The contrast between the fortunes of shareowners and employees couldn't be any starker than at General Electric. In addition to the post-recession wave of domestic plant closures -- the aviation plant in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the light bulb producer in Lexington, Kentucky, and the power turbine repair plant in suburban Pittsburgh, among others -- GE has pursued cuts in benefits and wages, which have hit both the union and non-union shares of the workforce. (About 13% of the company’s U.S. workforce is represented by labor unions.)

Two-tiered wages have arrived at union plants like those in Louisville, Kentucky, and Schenectady, New York, and non-union plants like the ones in Greenville, South Carolina, and Grove City, Pennsylvania. As part of its heralded “insourcing” push, the company has opened new plants stateside, but they typically offer lower compensation than the older ones.

Retirees have also felt the pinch. In September 2012, around 65,000 retired GE employees got word that, starting in 2015, their Medicare supplement plans would be replaced with smaller stipends once they turned 65. According to SEC filings, the move would save GE $832 million in 2012.

But it would cost retirees dearly. Dick Cress worked for 41 years at GE’s DeKalb, Illinois, motor plant, which closed in January. Now retired, Cress says he saw the price of his kidney drugs spike this year, from $30 to $840 a month, after his plan was canceled. “It came as a shock that they did this,” says Cress, 79. “Historically, GE has been very good to their employees.”

These stories didn’t sit well with Dennis Rocheleau, who spent decades facing off with union leaders as GE’s lead labor negotiator. He was deeply versed in the finer points of company benefits. When the health plan announcement arrived in his mailbox, he was incredulous. “I’d never seen anything like this done before at GE,” says Rocheleau, now 73 and retired.

Adding insult to injury was the $10 billion buyback program GE announced three months later in December 2012. “The buyback is a very troublesome element in all this,” says Rocheleau. Incensed, he spoke out at annual meetings over shareholder rewards and eroding retiree benefits. “A lot of people in the audience would come up to me and express incredulity,” he says.

The move, says a GE spokesman, falls in line with other large companies and offers “greater choice in coverage while striking a balance among our obligations to employees, retirees, and shareowners.”

In October of last year, Rocheleau filed a lawsuit in federal court, arguing that the changes contradicted company statements that it “expects” and “intends” to continue the plans “indefinitely.” The judge hearing the case indicated that it has a chance to move forward.

In the meantime, GE’s retirees will pay handsomely out of pocket for supplemental health coverage. “For 65,000 people, it’s just a very difficult switch to make,” Rocheleau says.

The Birth of Buybacks

American workers have grappled with wage stagnation for decades, as increased competition, new technologies and employer-friendly political reforms transformed domestic labor markets.

But Wall Street’s embrace of shareholder-focused management theories over the past three decades has also played a part in tightening the squeeze on workers, says William Lazonick, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Companies avoided buybacks out of legal concerns until a 1982 regulatory change, but repurchases didn’t really start taking off until the late 90s.

“Once the most important thing was keeping the stock price up, they stopped thinking about all the other things,” says Lazonick, a leading critic of shareholder value theory. Maneuvers to boost stock performance became ends in themselves, he argues, while investments in the workforce and new technology took a backseat.

There’s some evidence buybacks directly impact labor. Heitor Almeida, a professor of finance at the University of Illinois, studied firms that are just about to miss their forecasted earnings per share -- a metric closely watched on Wall Street.

These companies were more likely to increase share repurchases for a short-term pop; buybacks boost earnings-per-share numbers by decreasing outstanding stock. The drawback: “In the next quarter, they invest less and lay off employees,” Almeida says.

Complicating matters, many corporate executives have their bonuses tied up in earnings-per-share numbers. GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt, for instance, earned a 19 percent bonus in 2013 in part because GE’s earnings per share notched up.

Lazonick considers technology stalwart IBM to be the “epitome” of shareholder-focused corporate strategy. For decades, Big Blue boasted a lifetime employment policy and unrivaled sales. But changes in computing and global competition hit IBM hard.

Yet the company has still found a way to plow more than $100 billion into buybacks since 2000, as hundreds of thousands of employees have received pink slips.

Lazonick recently authored a report for the Brookings Institution titled "Stock Buybacks: From Retain-and-Reinvest to Downsize-and-Distribute," which argues that the corporate management philosophy that privileges stock buybacks contributes to income inequality. He cautions against drawing too direct a line between shareholder rewards and workforce decisions, but $2.5 trillion streaming from corporate balance sheets is hard to ignore. “The damage that buybacks can do is real -- but not all that visible,” Lazonick says.

A False Choice?

Though companies sitting on piles of cash often find themselves the targets of shareholder activists demanding payouts, like Carl Icahn at Apple, buybacks occasionally raise eyebrows. Some investors question their timing -- companies have a tendency to buy high and sell low -- while others disdain buybacks whose only purpose is to reduce the dilution of shares caused by overgenerous employee stock options.

"There's nothing wrong with looking out for employees, but remember: Shareholders are your owners," says Sizemore.

Repurchases might also signal that a company lacks innovative growth plans. “If the company doesn’t have great internal reinvestment opportunities, you wouldn’t want them to spend money on that,” Morningstar’s Coffina says. If everyone’s doing buybacks, though, something may be amiss, he says. “It doesn’t say good things about the long-term prospects of the economy.”

An IBM spokesman offered few details about workforce restructuring decisions, but pointed out that the company offers competitive benefits and has some 15,000 open positions. IBM Chief Financial Officer Martin Schroeter has written that the trade-off between productive investment and shareholder rewards is a “false choice.”

UPS also defends its shareholder reward program, arguing that buybacks have no correlation with workforce investments. “It’s a little bit of a misconception,” says Keith Colby, UPS’ director of investor relations. From an accounting standpoint, he says, the cash streams are independent.

But in talks with unions, Colby says, shareholder rewards invariably come up: “All aspects of the company’s financial decision-making are part of the discussion.”

The balance between shareholder demands and wages highlights a crucial fact: Labor generally doesn’t have any say in how companies dole out cash. “That’s not in the policy purview of the labor movement,” Lazonick says. “They don’t deal with corporate allocation of resources.”

When the union tried to save jobs at Fort Edward, GE’s buybacks never came up at the bargaining table.

GE wouldn’t comment specifically on how the company weighs share repurchase programs against other concerns. “It’s difficult to do that from where we are without getting into some grandiose theoretical debate,” says GE spokesman Dominic McMullan.

For others, the matter of how GE allocates resources isn’t as abstract.

“It’s real frustrating,” says Mark Rock, the assembly line worker in Fort Edward. “I know they make money.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.