High-Speed Black Hole Winds Heated Up By X-Rays Could Be Suppressing Star Formation In Galaxies

Black holes, as we all know, are voracious eaters. These objects are so dense that nothing, not even light, can escape once ensnared by their immense gravitational pull.

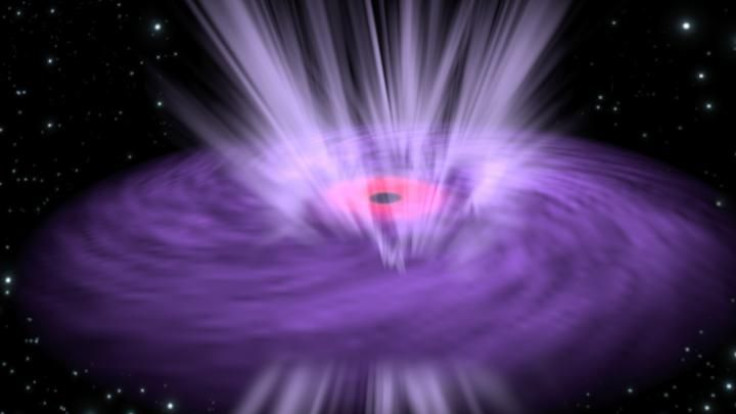

Occasionally, though, young and overeager black holes gobble down so much material so fast that they produce ultrafast “burps” of hot winds. Observations now conducted using NASA’s NuSTAR and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton telescopes indicate that these outflows, which can travel at nearly a quarter of the speed of light, could be suppressing the birth of stars in galaxies.

Although it has previously been suggested that black hole-driven jets and winds can inhibit star formation, this is the first time the temperature swings of these outflows has been measured and their interactions with a black hole’s radiation studied.

“We know that supermassive black holes affect the environment of their host galaxies, and powerful winds arising from near the black hole may be one means for them to do so,” NuSTAR principal investigator Fiona Harrison, a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology, said in a statement released Wednesday. “The rapid variability, observed for the first time, is providing clues as to how these winds form and how much energy they may carry out into the galaxy.”

For the purpose of this study, which was published in the March 2 issue of the journal Nature, the researchers trained their telescopes on IRAS 13224-3809 — an active galaxy located in the constellation Centaurus. This revealed that the ultrafast outflows emanating from the vicinity of the supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s center were heating up and cooling down in a span of just a few hours — hundreds of times faster than ever seen before.

This, the researchers said, was an indication that the outflows were responding to X-ray emissions from the accretion disk, which is an orbiting disk of dust, gas and debris that surrounds active black holes. The X-rays were heating up the winds to millions of degrees, pushing them past a point where they become incapable of absorbing any more X-rays.

These high-speed winds, in turn, could be responsible for suppressing star formation — a process that occurs at a temperature of roughly 10 Kelvin (-442 degrees Fahrenheit), at which point clouds of gas and dust cool down enough to condense.

However, further observations would be needed to better understand the role these winds play in regulating the environment within their host galaxies.

“We need to observe this black hole with better and more spectrometers, so we can get more details about these outflows,” study co-author Christopher Reynolds, a professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland, said in a statement. “For instance, we don't know whether the outflow is composed of one or multiple sheets of gas. And we need to observe on multiple bands in addition to X-rays — that would allow us to detect molecular gases, and colder gases, that can be driven by these high-energy outflows.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.