Immigration Reform: When Deporting Felons Breaks Families Apart

Raquel Garay lives just a few minutes’ walk from the U.S.-Mexico border, the line that has separated her from her family for more than two years. Since being deported from the U.S., where she lived for more than 40 years, in 2013, she lives alone in a country that feels foreign to her while her husband, children and grandchildren remain just a few hours away, across a border bridge she can’t cross.

The story is familiar for many deported immigrants, potentially hundreds of thousands, who have been torn away from their families in the United States. It’s what spurred President Barack Obama to pledge last year a smarter immigration policy that focuses on deporting “felons, not families.” While he has pushed executive action to shield those with strong family ties in the U.S., he has also touted an 80 percent increase in the number of immigrants with criminal convictions deported from the U.S. during his presidency.

That stirs conflicted feelings for Garay, who is a convicted felon who was removed from the U.S. for a deportable, although nonviolent, offense -- and also a mother, grandmother and wife of U.S. citizens who had barely recovered from two devastating medical traumas in the family before their lives were again upended by her deportation.

"It’s affected all of us here,” said Mario Jr., Raquel’s 24-year-old son. “They separated a family.”

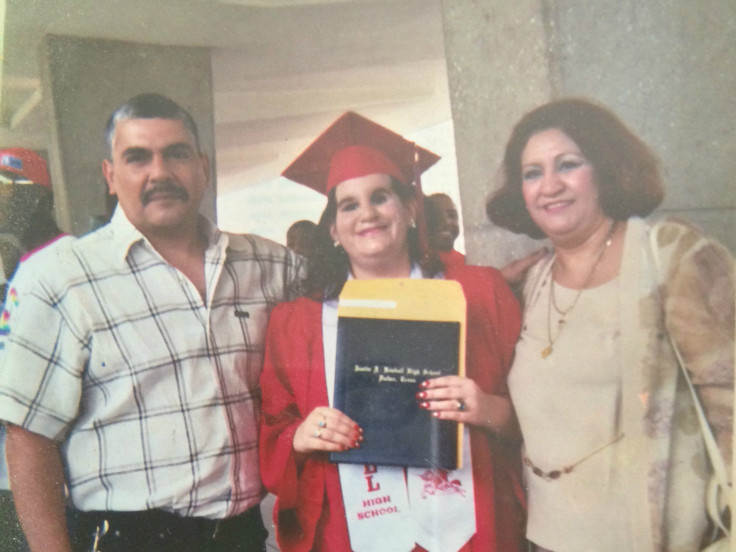

Raquel, now 54, had lived in the United States since age 12 after her parents brought her over the border in the 1970s. Eventually she married Mario Garay, a U.S. citizen, got her green card and built a home and family with him in Grand Prairie, Texas.

But soon, the Garays discovered that their infant daughter Celia was having problems with her sight. After going from doctor to doctor, Celia eventually was diagnosed with retinoblastoma, a rare form of eye cancer. But the cancer already had progressed by the time the diagnosis came, and the Garays had to have both Celia’s eyes removed.

While Mario worked to support the family, Raquel ferried Celia to a slew of specialist visits and treatments while helping her navigate the world without sight. Eventually, Celia’s condition stabilized and Raquel enrolled her in a school for the blind. But years of stress and worry already had taken their toll, and during that time, Raquel said, she began to make mistakes.

“I got into a lot of trouble in my relationship with my husband, with my drinking,” she said. “I was thinking of the future -- what was going to happen with my daughter? She was blind, and she was going to be blind forever.”

In 1997 she was arrested for possession of a controlled substance: less than 3 grams of cocaine found in her car. She was convicted of a felony and deported in 2000.

“I had a lot of anger and a lot of sadness,” Raquel said. “I was going through a lot of trauma with my daughter's cancer. It’s something you never get over.” But she acknowledges it was still a grave lapse of judgment on her part. “I know I made a lot of mistakes,” she said.

Deported immigrants who have criminal convictions typically have to wait 10 years before they can re-enter the U.S. legally. But Raquel’s children still needed care.

“My mother was my eyes,” Celia said. “Our family was like a puzzle that needed to be completed. So we went back and got her. We needed that other piece.” In the pre-9/11 era, border security was far less stringent than today. Raquel told border guards she was a U.S. resident and easily crossed back into Texas.

But another trauma soon struck: Her third and youngest child, Richard, was diagnosed with aplastic anemia, a bone marrow disorder similar to leukemia. Again, the Garays found themselves scrambling to save another child’s life, with Raquel making multiple trips a week for endless rounds of specialist visits, blood transfusions and treatments.

“She stayed by my brother’s side through the blood transfusions, the bone marrow biopsy, the liver biopsy, the chemotherapy, the radiation, through the late night throw-up, changing the bed sheets, the cold nights,” Celia recalled. “She stayed with him day and night in that hospital. If she had been in Mexico, we might have lost him, because nobody fights for a child the way a mother does.” Eventually Richard survived too, thanks to a bone marrow transplant. Raquel, meanwhile, steered clear of the substance abuse she had fallen into before she was deported.

The worst of the Garays’ ordeals seemed to be over. But in 2012, Raquel went to renew her driver’s license, which put her decade-old felony conviction and deportation on authorities’ radar. Immigration officials arrested her outside her home, detained her and deported her again to Mexico in January 2013.

This time the move seemed final. After spending six months in detention, an experience Raquel described as harrowing and rife with mistreatment, she didn’t want to risk ending up in immigration authorities’ custody again. The Garays consulted attorneys, wrote letters to lawmakers and started petitions to find a way for Raquel to return, but to no avail. “Our whole family was in pain for her. We tried everything we could,” said Imelda Fuentes, Raquel’s sister, who also lives in Texas. “We talked to so many different attorneys, and everyone told us no.”

“I can talk to her whenever I want on the phone, but that’s not the same as seeing her,” Mario Jr. said. “What if something happens to one of us here? She would have to stay over there. She wouldn’t be able to come see us, or visit the hospital, or come to a funeral. It’s not right.”

“When I think of a felon, I think of somebody who hurts other people, or steals,” Mario Sr. said. “She hasn’t done any of those things.”

“Millions of families have been destroyed. It’s not just me,” Raquel said. “I haven’t committed any crimes since 1997. I just want to be back with my kids.”

While Raquel sees her children a few times a year, during holidays when they can take the time to visit her, Mario visits more frequently, taking the eight-hour drive once a month to Mexico. However, his job, running a hardwood flooring business in Texas, prevents him from moving there to be with her. “There wouldn’t be anywhere for me to work if I moved down there with her,” he said.

“My husband is working so hard, and he has to travel all the time,” Raquel said. “It’s not like we’re youngsters. We’ve been through a lot, and he has to work twice as hard to pay for me. When I see him, he doesn’t look the same anymore. He’s tired, and there’s nothing I can do to help him.”

Raquel settled in Piedras Negras, the Mexican border town where she was born. She went back to school there, finished her degrees and got a job teaching English. But living in Mexico, particularly in a high crime area, makes her and her family uneasy. She’s not fluent in Spanish and knows little about Mexico’s customs and legal system. “The people are different. They look like you but they’re totally different,” she said. “The laws are different, the food is different, the money is different. And I’m alone.”

“She’s so happy when we come to visit,” Imelda said. “She cries for joy. But then we have to leave.”

Depression, anxiety and high blood pressure also have delivered blows to Raquel’s physical and emotional health. The Garays are counting down the years until she’ll be able to re-enter the U.S. legally -- her deportation order mandates at least a 10-year wait before she can attempt to come back, but there's no guarantee she would be able to secure a visa or live in the U.S. again. There's also a strong fear that her health might not hold up until then. “The medical facilities there, it’s like playing doctor at home compared to a top-dollar hospital,” Celia said. “She’s dying and there’s nothing we can do to help her.”

Immigrants convicted of felonies rarely elicit sympathy from immigration courts or U.S. policymakers. Felony convictions automatically strip permanent residents of their status and invalidate undocumented immigrants’ eligibility for the deferred-action programs Obama has passed by executive action in recent years.

The bipartisan immigration reform bill passed by the Senate in 2013 included a provision for deported parents to rejoin their families in the U.S. under certain conditions. That bill has languished amid political deadlock in Congress -- and the provision doesn’t apply to those deported because of criminal offenses.

The Department of Homeland Security also has designated felons as a top priority for removal, listed in the same category as immigrants involved in terrorist activities, street gang members and recent border crossers. The exception, DHS notes, is if there are “compelling and exceptional factors that clearly indicate the alien is not a threat to national security, border security or public safety and should not therefore be an enforcement priority.”

While Raquel's case may fall into that exception, the odds of finding a legal avenue back into the U.S. after deportation are extremely slim. Even more so with a felony conviction.

“You have to convince a court that you were wrongly deported and that they can actually require the federal government to let you back into the U.S.,” said César García Hernández, an immigration lawyer who runs the Crimmigration blog on the intersection of criminal law and immigration policy. “That is a very, very difficult course to pursue.”

The Obama administration increasingly has focused deportations on convicted criminals. According to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), 80 percent of interior removals from 2011 to 2013 (as opposed to to removals at the border) were for noncitizens convicted of crimes. But the MPI notes most of them were not for violent crimes or the most serious offenses, as deemed by the Department of Homeland Security.

In the first five years of the Obama administration, from 2009 to 2013, there were 242,231 deportation cases that, like Raquel’s, involved nonviolent crimes and removal orders that were more than a decade old, according to the MPI report. Drug possession convictions accounted for around 12 percent of 3.7 million deportations from the U.S. between 2003 and 2013.

“The Obama administration has been very aggressive about targeting migrants with drug convictions for detention and removal. They’re easy targets,” García Hernández said.

“The fact of the matter is that people who are outstanding family members also commit crimes,” he added. “One of the things that the Obama administration is obscuring by relying on the ‘family versus felons’ rhetoric is that individuals that may have criminal histories also have families. They’re making their lives in the U.S., but they are imperfect lives just like any citizen.”

But the idea of extending leniency to immigrants who have been convicted of crimes is not a wildly popular one. “When people commit crimes and get convicted, there is definitely going to be an impact on their families in more ways than one -- but crime is not a job Americans won’t do,” said Jessica Vaughan, director of policy studies for the Center for Immigration Studies, which advocates for more restrictive immigration policies. “There are 4 million people waiting their turn who qualify for legal immigration and have been sponsored by a family member or employer, who haven’t committed a crime. And yet they’re kept out.”

“Having a green card doesn’t make you immune from immigration laws. Neither does having a family,” she added.

The Garays still are searching for a legal clause or provision that could allow Raquel to rejoin her family in Texas. They’re also holding out hope for a shift in immigration policy, but acknowledge that it’s a very distant possibility.

“No matter what the law is, nobody understands the situation unless they’ve gone through it,” Celia said. “They [immigration authorities] are reading a piece of paper and using that to judge a person. She’s not a piece of paper. She’s a human.”

“Every day, I hope I’m going to get a call from somebody saying, ‘Your mom’s coming home,’ ” she said. “She saved two lives, and created three. Where’s the felon in that?”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.