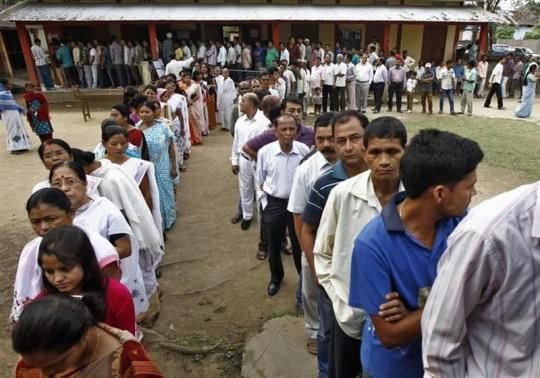

India’s 2014 Election To Cost $5 Billion, Second Only To Price Tag For 2012 U.S. Presidential Election

The 2014 general election in India is projected to cost about $5 billion, making it the costliest election ever in India and the second most expensive campaign in world history, behind only the 2012 U.S. presidential election, which cost some $7 billion, according to the U.S. Federal Election Commission.

The huge sum marks India’s entrance into big-time election expenditures as well as the emergence of sophisticated Western-style campaigning, fund-raising and the domination of social media in politics.

According to the Centre for Media Studies, an Indian think-tank, the $5 billion price tag for the Indian election will be about triple the amount of money spent by Indian candidates in the 2009 general election. Part of this spike can be explained by inflation, but also by the fact that politicians seek to appeal to a younger, tech-savvy Indian electorate with more easily accessible campaign venues, more television commercials, digital marketing efforts, closed-circuit live broadcasts of rallies and increased social media and Internet content.

The Indian Express reported that between 2009 and 2014, the advertising campaign budget of political parties alone more than tripled from $83 million to an estimated $300 million. “You are dealing with a new generation of 150 million [youthful] voters who like to see a sense of scale,” said Dilip Cherian, a partner at Perfect Relations, an Indian political campaign adviser, reported Time magazine. “The age of the street corner rallies is over.”

Narendra Modi, the leader of the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party, is especially keen on the use of social media to attract young voters, while the incumbent Congress party has “started spending on digital, which it never did in 2009,” said Mahesh Murthy, founder of Pinstorm, a digital marketing group. “[The political candidates] started [their campaigns long] before [the elections], and they are also focusing on states where they are traditionally not strong. They are leaving no area untouched,” said N. Bhaskara Rao, chairman of the Centre for Media Studies, in a statement.

Indeed, Modi has been campaigning since last year, aggressively crisscrossing the country to give speeches in front of huge, adoring crowds. The Diplomat reported that Modi’s fund-raising team consists of a seven-member group that includes Deepak Kanth, a former London-based investment banker, who has been tasked with generating donations from the wealthy Indian diaspora. Transportation costs are also skyrocketing – for example, Span Air, a private Indian air charter service, has already leased out all five of its aircraft to Congress through the end of the elections in mid-May at a daily cost of about $900,000.

Government rules stipulate that parliamentary candidates are allowed to spend a maximum of just 7 million rupees (about $116,000), but Reuters reported that the actual cost of winning a seat is in excess of $1 million, due to the costs of security for political rallies, transportation and other expenditures. Thus, the $5 billion estimate also includes online fundraising, advertising as well as “black money” (bribery) that some Indian political candidates often resort to in order to secure votes.

Campaign spending by the BJP has already come under fire from Congress, who accuse Modi of using “black money” in his massive advertising and publicity blitz. Anand Sharma, a Congress spokesman, told Indian media that Modi’s personal publicity campaign budget totals some 1 billion rupees (about $16.6 million), most of which he contends came from illegal sources. “Only 10 percent of this money can be accounted as ‘white money,’” Sharma told the CNN-IBN YV network. "Modi has frequently alleged the Congress of using black money, but all the black money seems to be in their camp.” Sharma also claimed that BJP’s election publicity budget is 25 times larger than that of Congress.

Modi has responded to the allegations by stating that he would be happy to turn over all his financial statements to the Election Commission. "I will myself write to the Election Commission saying that I will have no objection if the government wants to conduct a probe into the matter," he said.

On the other hand, given that India’s voting population is about four times as large as the number of eligible voters in the United States, some think the cost of the Indian election is actually quite a bargain. “I don’t think $5 billion for 800 million people is expensive,” said Mohan Guruswamy, a Delhi-based political analyst, according to Time. “Democracy doesn’t come cheap.”

In addition, this huge infusion of cash could provide a much-needed temporary pump for the floundering Indian economy, which is forecast to expand by less than 5 percent for a second consecutive fiscal year (about half the annual GDP growth rates the country delivered earlier in the decade). “This election spending largesse will help to boost Indian consumption expenditure over the second quarter of 2014, but this will be a temporary spike,” said Rajiv Biswas, the Asia-Pacific chief economist at London-based IHS Global Insight.

The Indian general election will also feature one of the most ambitious security undertakings ever in the subcontinent. Fearing outbreaks of attacks by Maoist guerillas, terrorist violence and communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims, the Ministry of Home Affairs has mobilized some 200,000 security personnel – comprising 175,000 paramilitary forces and 25,000 state police officers -- across the country to protect polling stations and safeguard election results. In the last general election in 2009, the central government-provided security deployment consisted of 120,000 personnel.

However, the Election Commission of India, the autonomous body that administers the polls, had requested an ever larger security force of some 240,000 officers for the 2014 elections. (These figures do not include the hundreds of thousands of other provincial police and local security forces that will be deployed to polling stations across the country). "Although I agree that the election process will be very long-drawn, it has been scheduled in such a manner that it will facilitate the movement of troops and ensure maximum security," said Ajay V. Nayak, chief electoral officer of the northeastern state of Bihar, one of the poorest and most violence-prone regions of India, reported Khabar South Asia.

Moreover, the majority of this year’s security contingent (about 160,000 individuals) has been dispatched to only six states -- Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Maharashtra, Bihar and Andhra Pradesh – reflecting the government’s concerns about the Maoist insurgents who concentrate their operations in those states. Maoists, who generally attack government forces in rural parts of central and northeastern India, killed nine people during the 2004 elections and another 24 in 2009. Security officials fear the number of poll-related deaths could be even higher this year, the DNA news agency of India reported.

Rajiv Kumar, the director-general of police in the state of Jharkhand, told the Khabar paper that intelligence reports indicate that Maoists have included senior political leaders among their intended targets during the polls. "They are planning to target vehicles deployed for electioneering purposes and vital installations, like railways and communication systems," Kumar said.

Indeed, Maoist rebels have already struck during the current elections. Agence France-Presse reported that three soldiers guarding polling officials in the state of Chhattisgarh in central India were killed by Communist guerillas. The three paramilitary commandos were ambushed as they escorted officials in a convoy about 260 miles south of the state capital of Raipur. Three other soldiers were wounded in another region of Chhattisgarh when they stepped on a landmine planted by suspected Maoist rebels. Maoist guerillas in Chhattisgarh have waged a violent multi-decade campaign against the state in a battle for land rights and to secure rights for indigenous, tribal peoples.

Khabar also reported that some security officials worry that with the massive deployment of armed officers to polling stations, Maoist forces may take advantage of the relative absence of a police/military presence in other regions by conducting attacks there. Zulfiquar Hassan, the inspector-general of operations for the Central Reserve Police Force, the largest of India's central armed police forces which functions under the control of Ministry of Home Affairs, called the election security scenario a “very tricky situation.” “The Maoists will utilize this period to execute their subversive plans with a view to instill confidence in their men, who are currently demoralized owing to the arrest and surrender of many of their top leaders," Hassan noted.

The states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar are also particularly vulnerable to communal violence pitting Hindus against Muslims. "Once we cover the Maoist-affected areas in southern and central Bihar, the troops will gradually move to the northern area, which borders Uttar Pradesh," Bihari electoral officer Nayak added. In the far northeast part of India, including the states of Nagaland, Meghalaya and Manipur which have long been marred by separatist violence and burdened by poverty and lack of development, security has also been beefed up during the polls.

Security will also be heavy in the northernmost part of India, Jammu & Kashmir, an area also claimed by Pakistan and the stage for a long separatist insurgency. Some 37 people were killed during the 2009 general election alone in Jammu & Kashmir.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.