Inside The Bold, Brazen And Bizarre Business Plan Of The Hyperloop

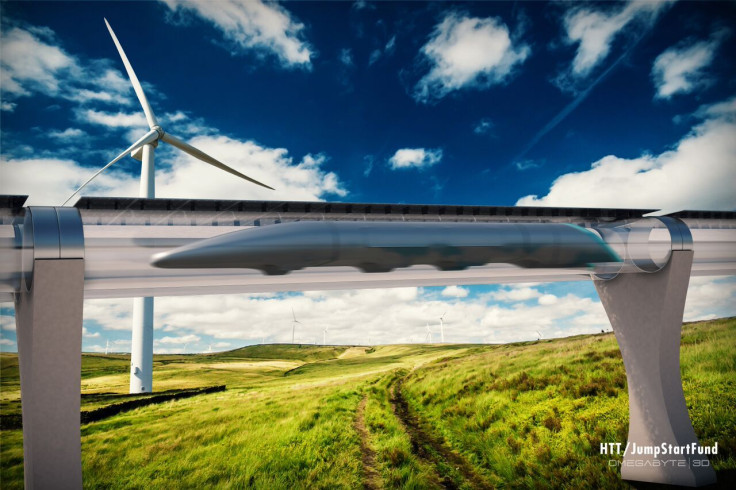

LOS ANGELES -- Up onstage in the sprawling Pasadena Convention Center stands Dirk Ahlborn, the German entrepreneur who wants to stick you into a 7-foot-wide tube -- suspended by magnetic forces in a pneumatic vacuum, naturally -- and shoot you from Los Angeles to San Francisco at a rate of 760 mph, about the speed of sound. “Just to explain it really simple,” Ahlborn tells the audience, “it’s a capsule full of people, hovering inside a tube, going very, very fast from point A to B.”

It’s late September and Ahlborn has been asked to deliver the keynote speech at the unfortunately named Gizworld conference, a three-day event whose tag line proclaims “the future is already here.” Though he’s not yet a household name, Ahlborn, founder of Hyperloop Transportation Technologies, is a natural pick for a futuristic event like this.

Two years ago, Elon Musk, the Tesla and SpaceX founder, published a widely publicized white paper that called for the building of a Hyperloop -- essentially a super-fast vessel that runs inside a vacuum-sealed tube. The idea for a “fifth mode” of transportation -- after planes, trains, autos and boats -- has floated around for about 100 years, but concerns over safety and cost have consistently scuttled the plans.

Still, Musk has been adamant that advances in technology make the time right for a Hyperloop, or a system like it, one that is far more audacious than California’s already-proposed 200 mph high-speed rail line, which, in addition to being very fast, would also be very expensive, at a cost of some $68 billion.

Still, Musk had no intention of building the Hyperloop himself. It was part public exhortation, part public dare. In essence, Musk lobbed the idea into the ether and just sort of hoped that a company -- or a person -- would turn the notion into a reality.

Ahlborn is the guy who took the bait.

Back onstage, Ahlborn is describing how the company he formed is itself on the fast track to building the Hyperloop. What he doesn't mention, however, is that in February a separate and competing Hyperloop concern was announced.

Similar Names, Different Approaches

The similarly named Hyperloop Technologies, run by Shervin Pishevar -- a former SpaceX engineer and Silicon Valley investor -- opened up in Los Angeles not far from HTT's headquarters. But despite their similar names, much to the chagrin of Ahlborn, the two companies could not be any different in their approach to prototyping, building or commercializing the Hyperloop.

In one corner, Pishevar's company is taking the more traditional, Silicon Valley route: It's raising gobs of money from venture capitalists, hiring employees and starting to build out potential Hyperloop prototypes right from the courtyard of its freshly appointed headquarters in downtown LA.

By contrast, Ahlborn's company is the renegade, the company that the Los Angeles Times recently described as “the radical” of the two companies. Why? Because Ahlborn and HTT aren’t simply trying to rethink the physics of transportation, they’re attempting to rethink how companies are built in the first place. Rather than hire full-time, salaried employees, Ahlborn has decided to crowdsource the labor to part-time workers and offer stock options in lieu of salary.

Amazingly, it’s beginning to work.

Since launching in the summer of 2013, Ahlborn's company has grown to about 450 workers, based in more than a dozen countries. Many of them work for organizations like NASA and Boeing during the day and spend nights and weekends working for Ahlborn. In order to be eligible for stock, HTT asks its “employees” to commit to a 10-hour workweek. Ahlborn declined to get into specifics about stock allocations for this story, but in an email he noted: “Early [employees] get more. In general we have a difference between senior and junior people for each hour worked.”

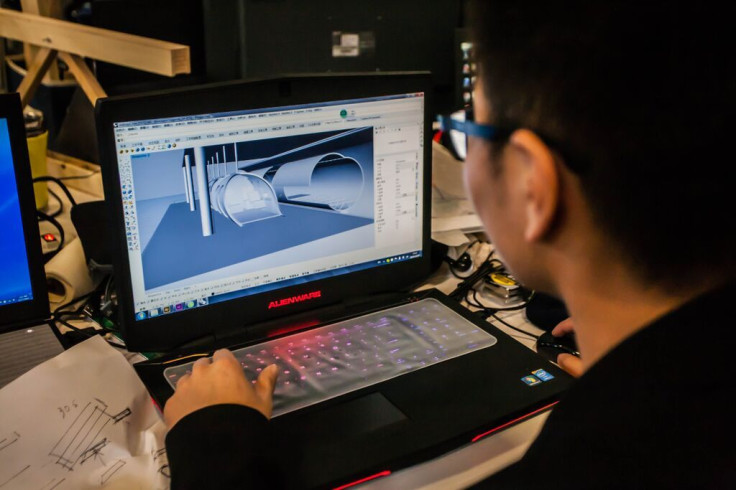

Yayun Zhou, HTT’s design director, recently completed her master’s degree in architecture from the UCLA. She’s now helping design the interiors for HTT, forgoing the stability -- and paycheck -- of a more traditional salaried gig. “Everything is going really fast,” she says. “We’re very focused.”

Eventually, those employees may indeed cash in on their efforts. By the first quarter of 2016, Ahlborn has a bold plan: He wants to take the company public, raising upward of $500 million on the Nasdaq, with the money being used to compensate those who stick with the company, as well as finance a test track in California’s Central Valley.

'Back To Basics'

Later, hunched over a tomato soup and salad lunch near the conference center, Ahlborn reflects on his chosen model of doing business. “I hate the name 'crowdsourcing,'” he says. “At the end, it’s community. We used to come together to build houses together. It’s back to basics.”

Ahlborn, who stands well over 6 feet tall and has a snarling tattoo up his shoulder that peeks out from his button-up shirt, has been described by associates with various terms -- “visionary,” “honest” and a “big German guy that never smiles,” just to name a few.

Born in Berlin, Ahlborn lived most of his adult life in Italy, where he started a string of companies, including a pellet stove business and a maker of high-quality fireplaces. In 2010, Ahlborn moved to the United States and, in 2013, at the height of the crowdfunding after the 2012 enactment of the JOBS (Jumpstart Our Business Startups) Act, Ahlborn launched the JumpStart Fund, where would-be entrepreneurs can post ideas and hope to get people interested in working on them in exchange for company stock.

The international experience should serve him well. Ahlborn said he doesn't actually believe the path to commercialization of the Hyperloop will happen in the United States. While the idea for a Los Angeles-to-San Francisco route will likely sound appealing to millions of Californians, Ahlborn isn't really bent on selling the technology locally. He believes markets like China and India, where a "small" city might mean something like 20 million residents, could find it more useful. And he says for that reason overseas governments are more willing to act quickly.

"We’re not going to do this in the United States," he says. "If we were to try and do this in the U.S., it would take 20 to 30 years."

To help get attention for JumpStart, he launched the platform on the heels of Musk’s Hyperloop announcement, despite not having a particular expertise in transportation or the physics of supersonic travel. Ultimately, his lack of expertise hasn’t really mattered much because he has been able to attract top-tier talent to work for the company.

“The guys are working for stock options -- they’re doing 10 times better job [than paid employees]," he says.

It’s not just solo workers getting involved, either.

Andrew Liu, a vice president at Aecom, one of the world’s largest engineering design firms, headquartered in Los Angeles, actually signed up his entire company, and says there are about two-dozen employees within Aecom currently working on the Hyperloop project. Right now, those employees are preparing an environmental-impact report, providing more detailed conceptual designs and developing a more realistic cost assessment for the project.

“There’s a lot of different things we need to do,” Liu says.

Liu admits that actually building Hyperloop systems around the United States would be a Herculean challenge. Beyond cost, they’d have to convince government officials and regulators that it’s actually safe enough for passengers. “In order to get the revenue you need, you need to send a pod every 30 seconds,” Liu says. “What happens if one breaks down and you have a pileup?”

Still, Liu says Aecom is participating for a couple of reasons. First, because it’s a potentially “transformative” project, and Aecom wants to be involved. Second, it's also helping get employees -- many of whom might be a little sick of building mundane highways -- get excited about building something new.

“So many employees are so excited,” Liu says. “You have to imagine what it does from a recruiting perspective. It’s win-win. The exciting part is seeing how this is changing the paradigm within our own company. This is a sexy project.”

Another key partnership for HTT is the Swiss-based Oerlikon Leybold Vacuum, which was also announced last February.

Sucking The Air Out

Without getting too deep into the science of how the Hyperloop will work, it's imperative to understand that the air must first be sucked out of the system. It’s like that old science experiment in which a feather is dropped in a vacuum-sealed container. It falls like a stone because there’s no air resistance. So in order for the Hyperloop capsules to speed through the tubes at extremely high velocities using magnetic forces, the air first needs to be pumped out of the tubes.

And for that, they basically need giant vacuums.

Carl Brockmeyer, head of business development at Oerlikon Leybold Vacuum, says he emailed Ahlborn out of the blue when he heard about the Hyperloop project.

“Ahlborn is very quick, very open,” Brockmeyer says. “He’s a visionary. It’s very different from the conventional customers we have. The reason we want to be involved is because we are a tech company, and we want to share a seat on the podium to work on new projects. This is in our bloodstream. This is part of what we do.”

In the next couple of months, Ahlborn says his company will raise as much as $50 million from strategic investors (though he declines to mentions who just yet) and by the second quarter of 2016, once the company goes public, Ahlborn says the company will break ground on a stretch of land in central California.

To get to that point, Ahlborn needed to find a suitable partner. After all, how many private entities would be willing to let him build a test track on their land -- for free?

Earlier this year, Ahlborn found his match: Quay Hays, builder of Quay Valley, a sort of utopia being built in California’s Central Valley, halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. “Quay Valley is going to be huge for us,” Ahlborn says.

Sitting in his 16th floor office overlooking the Hollywood Hills, Hays gestures across a massive conference-room table cluttered with plans for the futuristic, energy-efficient village he envisions will some day have some 75,000 residents. Hays is a third-generation California developer, and is no stranger to developing large swaths of land. He says he has been obsessing for years about how to build sustainable communities -- especially one without cars and traffic. When he saw Musk's white paper, he said he began "tracking" companies involved in its implementation.

“It still amazes me that we all hop into big hunks of metal with rubber and have to use those to get from point A to point B,” he says.

In February, Hays and Ahlborn signed a deal that would allow HTT to build a 5-mile test track adjacent to the village on land now used for cattle grazing. “The Hyperloop seemed to be a good fit with what we’re doing, which is challenging traditional wisdom in every aspect of development to see if there’s a better way. It’s the 21st century, and in 99 percent of the cases, there is a better way.”

Asked about Ahlborn’s approach using crowdsourced employees, Hays was unfazed. “I can relate to what Dirk is doing,” he says. “It’s the way to get the best talent.” Later, he added: “Something’s got to give. It’s going to take these pioneers in transportation to get it done.”

Cost Per Mile

Pioneering a new transportation system is one thing, but the question of revenue and profit is another. Even though the idea sounds fantastic -- even revolutionary -- Ahlborn is constantly reinforcing that Hyperloop isn’t merely a fantasy cooked up by Musk. Right now, the company estimates that building the tubes would cost $20 million to $45 million per mile, compared to the $200 million per mile for a bullet train. Overall, for a 400-mile track, HTT estimates the cost to be around $16 billion.

“Why not build a bullet train? Because a bullet train is the worst investment you can make,” Ahlborn says. “It’s the cost, the liability. You continue paying for it. It doesn’t make economical sense. It’s old technology. What we’re working on, it’s not the speed. It’s the business model.”

Bibop Gresta, Ahlborn’s business partner, explains a ticket would cost $30, and each capsule would transport 28 people. For a journey from San Francisco to Los Angeles, one capsule would be dispatched every 30 seconds. Assuming full capacity on each trip, Gresta says the company would make about $24 million per year, and be profitable within eight years, assuming it can build more than one tube.

Still, Gresta says ticket prices will be just one source of revenue. He says solar panels placed along the track would produce excess energy that could be sold to nearby municipalities. And then there’s the matter of “monetizing the user.” “We also have all your data,” Gresta says.

Both Gresta and Ahlborn say advertising will be another source of lucrative income.

“Anything is advertising, because it’s data,” Ahlborn says. “From data, I can learn more about you. It’s about incorporating different business models into [the Hyperloop]. I know where you’re coming from, I know where you’re going, I can offer you solutions so that your experience is better, faster, simpler.”

Right now, though, it’s all just a pipe dream, so to speak, at least until the Quay Valley launch. Ahlborn says that in all likelihood, revenues generated from the Quay Valley track won’t be coming in until at least late 2018.

“I always tell everyone it’s a marathon, not a sprint,” Ahlborn says. With 450 workers and growing, Ahlborn adds, “It is becoming a movement.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.