Investors Mark Unhappy Anniversary at Allen Stanford's Trial on Friday

Defense lawyers made a case for Allen Stanford's innocence on Friday in a courtroom filled with people who claim he stole millions of dollars of their savings.

Some two dozen investors were at the federal courthouse in Houston to mark the third anniversary of the government closure of Stanford Financial Group in February 2009.

During a break in the testimony, Angela Shaw, founder of the Stanford Victims Coalition, said that three years without restitution had made a mockery of those people.

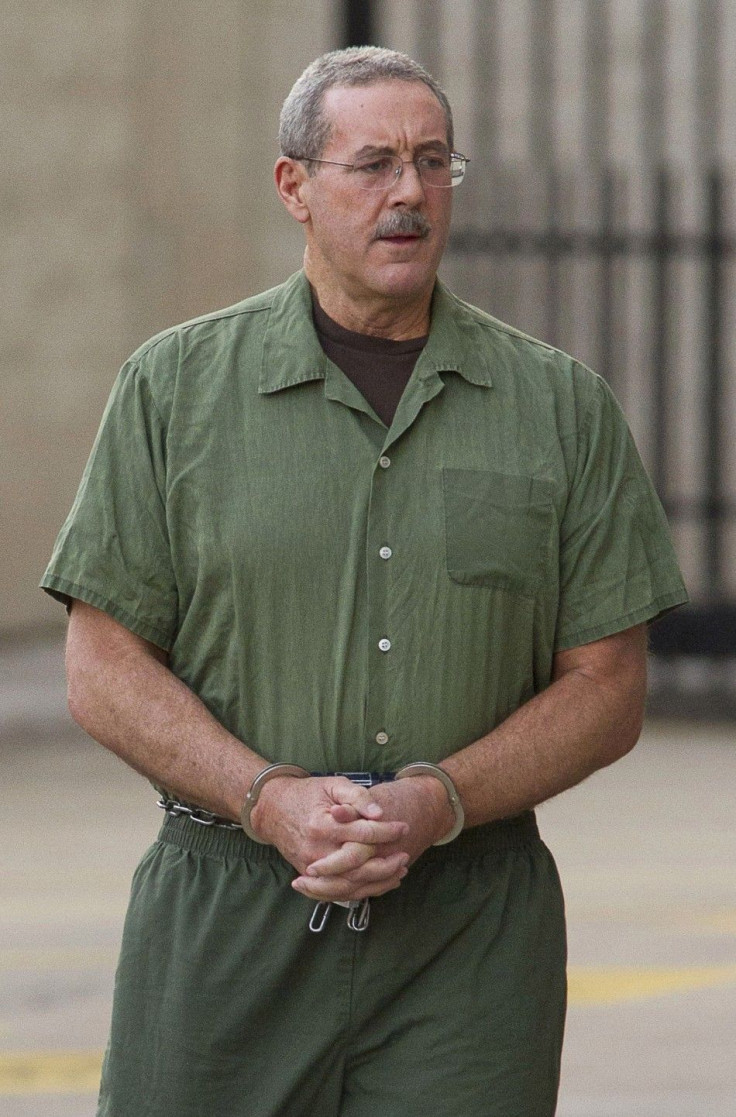

The trial -- where the former Texas financier stands accused of orchestrating a $7 billion Ponzi scheme -- got under way on Jan. 23. Prosecutors contend that Stanford stole money deposited at Stanford International Bank in Antigua and spent it on girlfriends, mansions, private jets, and yachts.

Stanford, 61, has pleaded not guilty to 14 counts, and his defense lawyers have argued that he was not responsible for any fraud because he left day-to-day business decisions to underlings.

Defense attorneys have said they will show that Stanford's former top deputy James Davis, not Stanford himself, had oversight of funds invested in the Stanford International Bank. Davis has pleaded guilty to fraud and testified against Stanford.

On Friday, former Stanford aide Linda Wingfield testified that Davis had fought her efforts to enforce policies to control company expenses. He would ignore the policies, she said.

Testifying by video from Orlando, Fla., because she was unable to travel to Houston, Wingfield said she had expressed concern at the time that Davis had sole responsibility for certain internal audits of operations at Stanford International Bank.

Under cross-examination by the government, Wingfield said that when she emailed Stanford expressing concerns about Davis, Stanford said she should not have put them into writing.

Davis was a star witness during the prosecution, which rested its case on Wednesday. He testified that he and Stanford cooked the books of Stanford's bank and regularly withdrew millions of dollars from a secret Swiss bank account that was funded with investor money.

But, under cross-examination by Stanford lawyer Robert Scardino, Davis admitted that he was a liar and a serial adulterer and that he had committed fraud.

The government also showed jurors numerous emails to and from Stanford authorizing transfers of money from a secret Swiss account. Former employees also testified that Stanford made all big decisions.

Legal experts said that through the weight of its evidence, the government had set a high bar for Stanford's defense team.

The defense has done a very good job of beating up Davis, said Wendell Odom, a criminal-defense attorney based in Houston who has been monitoring the trial. But it's going to be difficult to prove that Stanford did not know what was going on, he said.

It is unclear whether Stanford will testify. His legal team has argued that he is not competent to aid his defense because of brain injuries from a jailhouse fight in 2009 and an addiction to anti-anxiety drugs.

But because the judge has ruled that Stanford is competent, the only way to reopen the issue would be for him to testify. Such a move would be risky because it would give prosecutors a chance to question him.

When they began their defense on Wednesday, Stanford's attorneys gave the judge a list of 27 defense witnesses. Stanford was not among them. Judge David Hittner told the jury they should not infer from the absence of his name that Stanford would not testify.

As the trial unfolded, investors such as Jim Eccles of Austin, Texas, thought about people who had been defrauded by Bernard Madoff. They recouped some money, said Eccles, who was in court on Friday, but Stanford investors have gotten nothing.

Madoff, 73, is serving 150 years in prison for the Ponzi scheme he perpetrated on investors.

Madoff confessed. This one has not, said Eccles. We have to prove he did it. Eccles said he had lost more than $1 million invested in certificates of deposit at the Stanford International Bank in Antigua.

The case is USA v. Stanford et al, U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, No. 09r-00342.

(Reporting by Eileen O'Grady and Anna Driver)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters {{Year}}. All rights reserved.