Israel should learn to live with more enemies after Mubarak

Israel has launched a diplomatic offensive as speculation intensified that the U.S. and European allies were ditching Egypt's beleaguered president Hosni Mubarak.

The Haaretz daily reported on Tuesday the Israeli foreign ministry has issued a directive to around a dozen key embassies in the U.S, Canada, China, Russia and several European countries asking ambassadors to impress upon allies of the need to ensure political stability in Egypt.

Israel fears its decades-old peace with Egypt will crumble if Mubarak is replaced by a populist regime which by all means will be inimical to the Jewish state.

A Gallup poll conducted in 2008 showed that as much as 64 per cent of Egyptians wanted their country to adopt Islamic law, according to a report in Maariv newspaper last week.

Other newspapers warned that the rise of Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt will hurt Israel's security. If the Muslim Brotherhood grabs the reins … the impact on Israel will be immediate, wrote the Jerusalem Post.

To make matters worse, Jordan, the only other country in the region with which Israel has peaceful relations, is also witnessing civil unrest. Last year, Israel lost friendly ties with Turkey in the aftermath of the military action on the flotilla carrying humanitarian supplies to Gaza. And recently a Hezbollah-backed primie iminster was instituted n Lebanon, following Rafik Hariri’s exit.

Israel is definitely getting lonelier in the region.

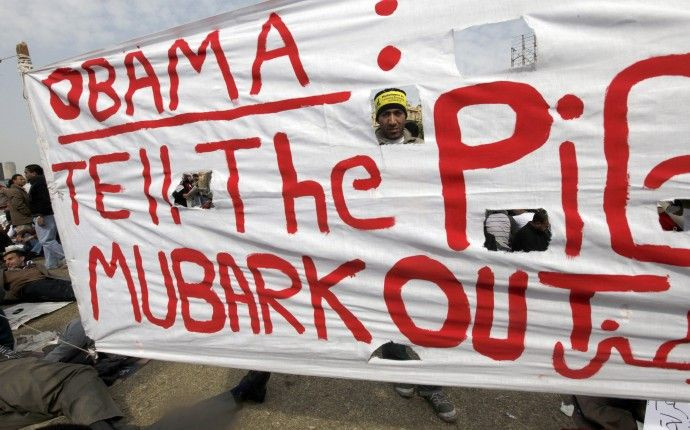

Ironically, Mubarak's support of Israel was one major factor that alienated his people. Common people in Egypt are fierce suporters of the Palestinian's struggle for freedom from Israel's clutches. Most of them also support Hamas, the worst enemy of Israel. There has been vociferous calls from Egyptians to open the Rafah crossing-point into Gaza.

Large constituencies in Egypt demand the withdrawal of diplomatic relations with Israel and even arming the Hamas, according to an article written by Robert Fisk in The Independent.

But Mubarak remained a tough customer all along. He remained a loyal ally of Washington from where his government got massive aid as well as military hardware.

He rebuffed popular demand for a tougher line on Israel citing international dynamics. And there is a kind of perverse beauty in listening to the response of the Egyptian government: why not complain about the three gates which the Israelis refuse to open? And anyway, the Rafah crossing-point is politically controlled by the four powers that produced the road map for peace, including Britain and the US. Why blame Mubarak, Fisk, the archetypal chronicler of Middle East politics, wrote.

And Israel's Netanyahu recognizes the weight of the moment. For the first time since the 1979 peace treaty, Israel has allowed Egyptian military into the demilitarized Sinai peninsula to confront protesters demanding the resignation of president Hosni Mubarak.

The move displays how important the continuance of the Mubarak regime is for Israel. The Jewish state has also called upon western allies to tone down criticism of Mubarak. Prime Minister Netanyahu has asked his cabinet members not to make public comments on the Egyptian crisis.

The possibility of Egypt slipping into the hands of a radical Islamist regime is certainly unthinkable for Israel.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.