Ling Jihua Corruption Probe: Communist Party Already Plans To Control Commentary

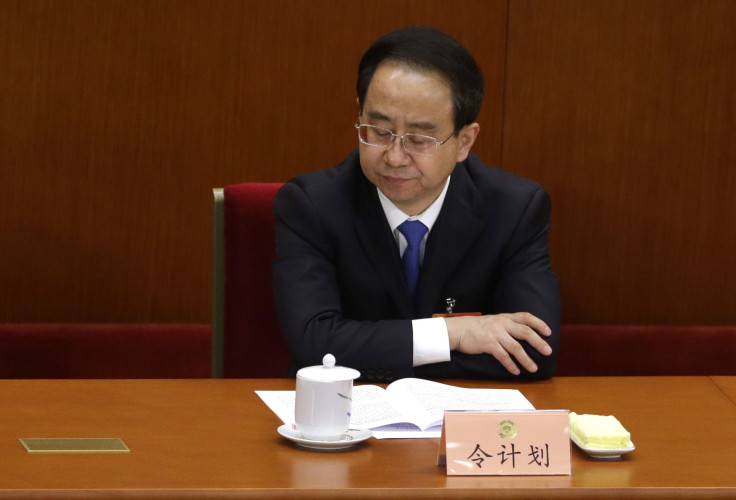

A little more than a week after the announcement of the expulsion of Zhou Yongkang, recently one of China’s top security officials, from the Communist Party, the government has announced an investigation into yet another high-ranking official. Once serving as a top aide to President Hu Jintao, who ruled from 2002 to 2012, Ling Jihua was on the fast track to the Politburo Standing Committee, China's top policy-making circle.

That all ended with the announcement on Monday that, after a public scandal involving his family, Ling is under investigation, a target for the government’s anti-graft agency.

A quiet announcement by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the party’s watchdog committee, said the 58-year-old Ling is under investigation for “suspected serious disciplinary violations,” which is often understood to be a euphemism for corruption.

The investigation into Ling has made waves in the foreign press, but very few details have been revealed by state media. China Digital Times cited an alleged memo sent to state media, saying that coverage of the case should be controlled: “Content related to Ling Jihua must strictly abide by propaganda discipline. Do not act on your own to hype the issue. Strictly control online commentary.”

The party’s decision to control conversation about the Ling probe is not unusual. As in the previous cases of Zhou Yongkang and Bo Xilai, the central government often uses state media to give the party time to calibrate its position, simultaneously informing the public and still avoiding making a big deal out of it, to avoid tarnishing the reputation of the government. Once the party investigation is completed, the case will be turned over to the judiciary, even though the outcome will already be unofficially known if the Zhou and Bo cases are any guide: Ling will be sentenced to a long prison term.

China’s recent history offers hints for how media and social media will handle Ling’s case. In 2012, after the initial announcement of his arrest, phrases related to Bo Xilai and his arrest were blocked from popular social media sites. After he got a life sentence, however, the social media ban was lifted, with photos of Bo’s trial being shared on microblog Weibo tens of thousands of times in just a few hours.

Ling's downfall can be traced to the death of his son, Ling Gu, who perished in 2012 in a fiery car accident while driving in his Ferrari. According to reports at the time, Gu was found naked with two women, one of whom was also naked, while the other scantily clad, leading investigators to believe Gu was driving recklessly, participating in a “sex game.” Before details hit the media, Ling reportedly tried to cover up the accident by paying off the families of the women involved and even denying the body found at the scene was his son. At the time, Ling was the chief of the Communist Party’s Central Committee General Office, a position that should have guaranteed him a spot in the Politburo under the following president.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.