Mexico’s Sonora Toxic Spill A Turning Point For The Environmental Movement?

Anger continues to simmer in Mexico nearly two months after the country underwent what many have acknowledged to be its worst mining-related disaster in history. But the incident may also mark a critical juncture for environmental reform in Mexico, which has remained stalled for several years.

Local and federal officials are now gearing up to bolster environmental regulations after the Buenavista mine in Mexico’s northwest Sonora state – one of the world’s largest copper mines -- leaked around 10 million gallons of acid and heavy metals into the nearby Bacanuchi and Sonora rivers on Aug. 6. An estimated 22,000 people in seven surrounding municipalities faced the threat of a contaminated water supply; more than 80 schools closed for a week for fear that children would come into contact with toxic chemicals; and farmers and cattle ranchers along the river have lost huge revenue.

The accident remained front-page news throughout Mexico not just for the severity of the toll on Sonora residents, but also for widespread outcry against Grupo Mexico, the conglomerate that owns and operates the Buenavista mine. Local authorities slammed Grupo Mexico for reporting the incident almost 24 hours after the spill first began, at which point local residents had already detected a 40 mile (70 kilometer) orange streak running through the Sonora River.

The conglomerate also initially blamed heavy rains for causing the spill, which government authorities vehemently denied. “There were no heavy rains those days,” Mexico’s minister of environment, Juan Jose Guerra Abud, told the Wall Street Journal. Eventually, Grupo Mexico acknowledged that defective sealing on pipes in the mine was a factor in the spill.

“The company’s response has been terrible,” said Gustavo Alanis, an environmental lawyer and director of the Mexican Center for Environmental Rights. “They have tried to minimize the problem, hide the reason [behind] the problem, told lies, and have had no communication at all at the moments when it’s been crucial for them to be out there saying something.”

Grupo Mexico maintains that it responded promptly to the disaster and built a retaining wall to contain the spill in less than 24 hours. “We reject the punitive legal actions announced by the Federal Office of Environmental Protection, given the random nature of the incident and the prompt and complete response by the company,” it said in an Aug. 20 press statement. But under existing laws, the government was only allowed to extract a maximum fine of $3 million from the company, a sum dwarfed by Grupo Mexico’s $9.3 billion in annual revenue.

Anger against Grupo Mexico further intensified when government authorities sent out an alert over a new spill from the Buenavista mine on Sept. 21. This time, the spill threatened a waterway connecting to the San Pedro River, which flows into Arizona. Initial tests by Arizona state environmental officials showed the river was not affected by the spill; Grupo Mexico’s troubles avoided taking a transnational turn, at least for the time being.

But meanwhile, the ire of local and federal officials has prompted a new examination of Mexico’s laws on environmental accountability. "The economic fines are very low,” Alanis acknowledged. “[Legislators] have a responsibility to reform the environmental laws and other applicable laws in order to make sure that the fines are in balance with the damage.”

But Alanis said the environmental community was going full force to file lawsuits against the company and ensure that victims of the spill are fairly compensated. Meanwhile, the company agreed in mid-September to set aside a $150 million trust in order to pay for cleanup fees and damages, although some legislators had been pushing to cancel the company's concession to operate the mine.

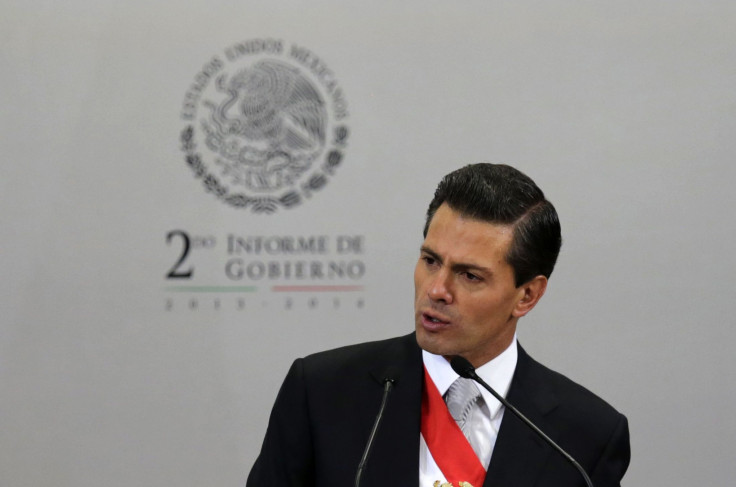

President Enrique Peña Nieto also acknowledged the need for reform in environmental accountability when he delivered his State of the Union address in early September, and Alanis said there were positive developments for environmental accountability after the spill, including a louder call for accident prevention measures in the mining industry and increased federal oversight of mining operations.

The Aug. 6 disaster “has to be” a pivotal moment for Mexico’s environmental movement, Alanis said. “We have no choice. If we don’t learn from this one, we will never learn.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.