Narwhal Physiology Combines Freeze And Flight Reactions When Stressed

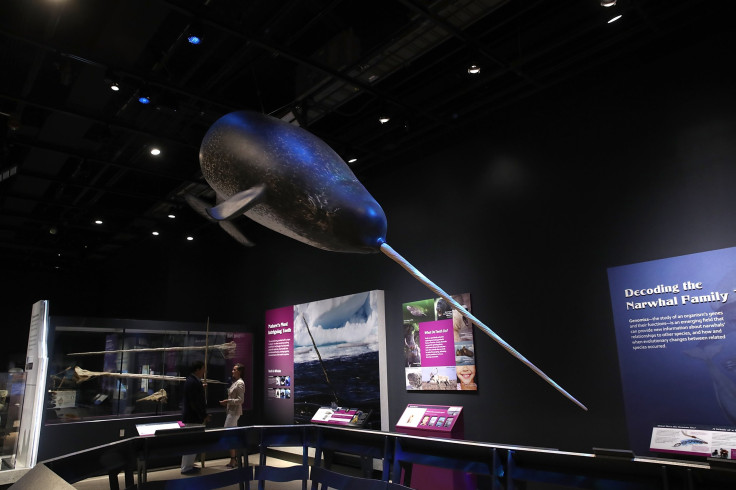

Narwhals are already among the more unusual creatures on Earth, what with being not just a marine mammal but with the long unicorn-like tusk that the males sport. Monitoring their heartbeats has shown another remarkable physiological trait — the simultaneous display of both freeze and flight reactions when stressed.

In their year-round habitat in the cold Arctic waters, narwhals sometimes get caught in fishing nets laid out by native hunters. Before releasing them, researchers put heart monitors on them to observe their behavior as they escaped. The mammals performed a series of deep-sea dives, swimming harder than usual, but at the same time, their heart rates dropped to just three or four beats a minute.

Talking about the potential impact of this combination on the oxygen supply to the brain, Terrie Williams, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at University of California, Santa Cruz, who has studied exercise physiology in a wide range of marine and terrestrial mammals, said in a statement Thursday: “How do you run away while holding your breath? These are deep-diving marine mammals, but we were not seeing normal dives during the escape period. I have to wonder how narwhals protect their brains and maintain oxygenation in this situation.”

When escaping killer whales or other natural predators, narwhals typically move slowly, either to great depths or to shallow coastal areas under a cover of ice, both the kind of places where killer whales won’t follow. But the relative speed, as shown in their response to escaping from fishing nets, is not a part of their normal behavior, Williams explained.

When mammals dive under water, a slowed heart rate is part of the normal response to conserve oxygen. In the case of narwhals, heart rates while resting on the surface was found to be about 60 beats a minute, which dropped to between 20 and 10 beats during dives, depending on the amount of physical activity. Even during a dive, exercise tends to increase the heart rate. But a decreased heart rate (called bradycardia) of three to four beats was never observed under natural circumstances.

The extremely low heart rate exhibited by narwhals when escaping from fishing nets is similar to what happens to other animals displaying a freeze reaction in response to perceived danger (think deer in the headlights). The other response, mutually exclusive to the freeze reaction, is that of fleeing from the perceived threat. Narwhals seem to be doing both.

“That’s what is so paradoxical about this escape response — it seems to cancel out the exercise response and maintains extreme bradycardia even when the whales are exercising hard,” Williams said in the statement. “For terrestrial mammals, these opposing signals to the heart can be problematic. Escaping marine mammals are trying to integrate a dive response on top of an exercise response on top of a fear response. This is a lot of physiological balancing, and I wonder if deep-diving marine mammals are designed to deal with three different signals coming to the heart at the same time.”

Compared to about 52 percent of the narwhal’s oxygen store being used up during normal dives, the mammals used up to 97 percent of their oxygen store on escape dives of similar depths and duration.

The narwhals being monitored were found to gradually return to normal heart rates, but Williams was concerned at the impact of human activity on the physiological capacity and behavioral responses of the animals. She used the example of other deep-diving whales, like beaked whales, whose strandings have been associated with human-generated noise in the oceans.

“The disorientation often reported during strandings of deep-diving whales makes me think something has gone wrong with their cognitive centers. Could this result from a failure to maintain normal oxygenation of the brain?” she said.

Williams and her colleagues studied the narwhals in Scoresby Sound on the east coast of Greenland. At present, it is mostly only native hunters in the region who set out nets to catch fish, seals and other animals, including narwhals. The hunters were co-opted by the researchers to allow them to attach monitors to the narwhals caught in the nets and to release them.

As Arctic sea ice melts, the region becomes more accessible to human activity, including fishing, tourism, and exploration for fossil fuel reserves.

A paper on the subject, titled “Paradoxical escape responses by narwhals (Monodon monoceros),” appeared online Friday in the journal Science.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.