NASA Rocket Findings Could Solve Mysteries About Sun’s Hot Outer Atmosphere

Scientists working on NASA’s Extreme Ultraviolet Normal Incidence Spectrograph, or Eunis, mission recently gathered some strong evidence that could explain why the sun’s outer atmosphere is much hotter than its surface. The new observations support a current theory about “a constant peppering of impulsive bursts of heating,” which are called “nanoflares.”

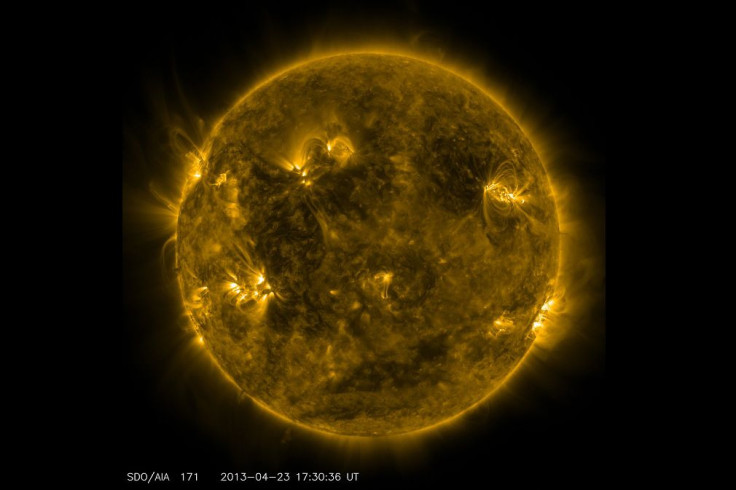

According to scientists, the heat on the sun’s visible surface, called the photosphere, measures almost 6,000 kelvins, while the corona, the aura of plasma that surrounds the sun, regularly reaches temperatures that are 300 times hotter. Scientists believe the new findings by the Eunis sounding rocket, launched April 23 of last year, will help them better understand the reason for this heat difference.

“That’s a bit of a puzzle,” Jeff Brosius, a space scientist at Catholic University in Washington and at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement. “Things usually get cooler farther away from a hot source. When you’re roasting a marshmallow, you move it closer to the fire to cook it, not farther away.”

The Eunis rocket, equipped with a very sensitive spectrograph to gather information about how much material is present at a given temperature, climbed almost 200 miles above the ground and examined a predetermined region of the sun that can often be the source of large flares and coronal mass ejections.

As light from the solar region streamed into the Eunis spectrograph, the instrument separated the light into its various wavelengths that are useful for spotting material at temperatures of 10 million kelvins, which is common among nanoflares.

“Scientists have hypothesized that a myriad of nanoflares could heat up solar material in the atmosphere to temperatures of up to 10 million kelvins. This material would cool very rapidly, producing ample solar material at the 1-to-3 million degrees regularly seen in the corona,” NASA said.

According to scientists, they scanned the data provided by the Eunis mission and spotted a wavelength of light corresponding to the 10 million-kelvin material. “This weak line observed over such a large fraction of an active region really gives us the strongest evidence yet for the presence of nanoflares,” Brosius said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.