NASA's Record-Breaking X3 Ion Thruster Could Propel Us To Deep Space

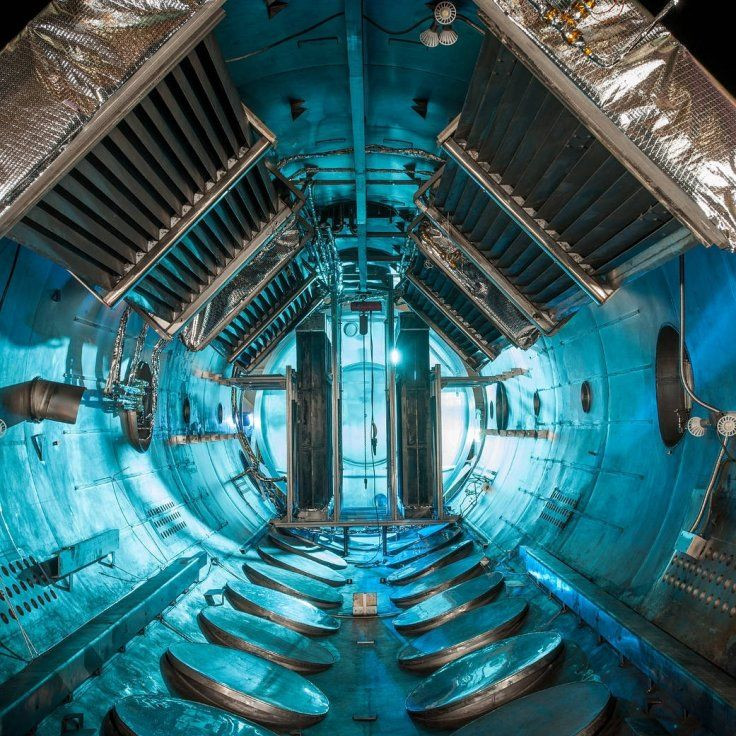

A plasma engine designed by researchers at the University of Michigan, in cooperation with NASA and the U.S. Air Force, called the X3 ion thruster has broken previously held records by operating at a record 102 kilowatts of power and generating 5.4 Newtons of thrust, breaking all existing records of power and propulsion.

The system uses a device called Hall thrusters which propels spacecraft by accelerating a stream of electrically charged atoms called ions.

According to an International Business Times UK report published Sunday, a recent demonstration conducted at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Ohio, showed the X3 breaking records for the “maximum power output, thrust and operating current achieved by a Hall thruster to date.”

Current thrusters used in rockets for space exploration are chemically fueled engines, which use liquid oxygen and hydrogen fuel.

Though this is a clean and powerful and abundant fuel source, it is capable of only reaching speeds of 3.1 miles per second. Whereas, Hall thrusters are capable of reaching 24.8 miles per second, said the report.

According to Alec Gallimore, head of research and dean of engineering at the University of Michigan, "We have shown that X3 can operate at over 100 kW of power. It operated at a huge range of power from 5 kW to 102 kW, with electrical current of up to 260 amperes. It generated 5.4 Newtons of thrust, which is the highest level of thrust achieved by any plasma thruster to date," Space.com reported.

The Plasma engines have much higher efficiency, and the mileage from these ion thrusters have surpassed all previous expectations.

"You can think of electric propulsion as having 10 times the miles per gallon compared to chemical propulsion," Gallimore said.

The only drawback with these ion-thrusters, according to the International Business Times UK report, is that chemical propulsion systems, currently, can generate many million kilowatts of power but ion thrusters can only generate 3 to 4 kilowatts.

According to Gallimore, the ion system needs to be built-up to a point where they can generate 20 to 40 times their current laboratory capacity and match chemical thrusters. Only then will they be able to successfully replace current propulsion systems.

The team hopes that tweaks and breakthroughs in ion thrusters can better the power output over the next decade, when they hope these thrusters will be ready to propel us into deep-space.

The team has already moved on to further develop the thruster. According to a report by NextBigFuture, the team hopes to run even bigger tests by next year. These tests will aim at producing and proving that the thruster can operate at full power for a non-stop period of 100 hours.

The engineering team is also very close to making a special magnetic shielding system for the thrusters themselves. This shield is being developed to keep the plasma away from the walls of the thruster system. This will prevent damage to the structure. It will also increase the reliability factor of these structures, says Gallimore, in the Space.com report.

The team hopes that, with or without this shield, a working model of the X3 would last over 1000 hours of non-stop operation in the future. The addition of a magnetic shield would help it run for years together, without maintenance checks or major hiccups.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.