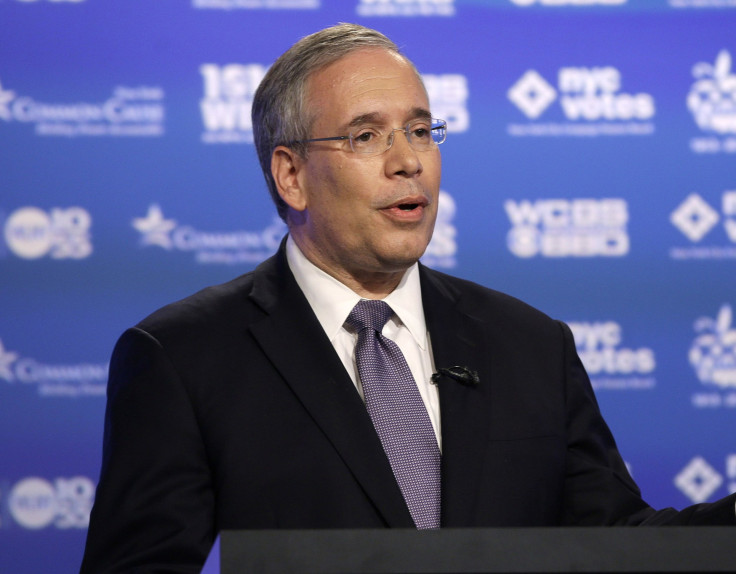

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer Pushes To Give Wall Street More Pension Cash

New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer has a relatively low public profile, but he’s the official in charge of one of the largest pools of capital in the world: When he speaks, the financial sector listens. So when he issued a report last week condemning the $2.5 billion in pension fees paid by New York City to Wall Street firms, he touched off national headlines about whether such expenditures by public retirement systems make financial sense.

“Money managers are being paid exorbitant fees even when they fail to meet baseline targets,” said Stringer, a Democrat. “Fees have not only wiped out any benefit to the funds, but have in fact cost taxpayers billions of dollars in lost returns. It’s clear that the status quo needs to change.”

With Stringer facing criticism for the city’s record-high fees, and with Democrats trying to channel the public’s anger at the financial industry, the report helped the comptroller portray himself as a crusader against Wall Street. Yet at the same time, Stringer is positioning New York’s pension system to potentially shift even more money into the types of high-risk investments that generate those eye-popping fees. He is the most outspoken proponent of legislation that would allow him to move billions of dollars of city workers’ pension money into private equity, hedge funds, real estate and other so-called “alternative investments” that tend to generate the highest fees of any investment class.

Meanwhile, for all their populist rhetoric in defense of the so-called "99 percent," major labor unions and the Democratic administration of Mayor Bill de Blasio have supported such a shift, which could send hundreds of millions of dollars in new pension fees to the 1 percenters in the financial industry.

Stringer’s office has justified the legislation as necessary for diversification.

“Comptroller Stringer’s report examined the value that the city’s pension funds have received relative to the fees that we pay,” a spokesperson for Stringer said. “Giving the funds greater flexibility to employ alternative asset classes goes hand in hand with our push to increase transparency around fees while demanding fairness and accountability in how our investment partnerships are structured.”

'Totally Schizophrenic'

Critics say the push into higher risk investments is fiscally dangerous -- and hypocritical.

“Did Scott Stringer get religion all of a sudden?” asked John Murphy, a former executive director of the New York City Employees Retirement System. “I don't understand how he's surprised to have found out that the pension fund is underperforming and overpaying for fees -- that’s been apparent forever. Alternative investments are the key drivers of fee growth. For Stringer to complain about fees while attempting to raise the [alternative investment allocation] is totally schizophrenic.”

Over the past decade, states and cities have shifted over a half-trillion dollars into alternative investments, data from the Pew Charitable Trust show. In its 2014 report, Pew noted that the shift “has coincided with a significant increase in investment fees” that exacerbate pension shortfalls.

The fees are supposed to buy investments that beat the stock market -- the idea being that investors pay a premium for outsized returns they cannot get elsewhere. But in recent years, those investments have often been outpaced by the stock market.

But with financial executives delivering big campaign contributions to public officials who oversee pension investments -- including Stringer himself -- the push into alternatives has continued. In the past four years, financial analysts have reported that large public pension funds increased their exposure to alternatives by 20 percent.

New York City’s $160 billion in pension assets make its retirement fund the fourth-largest in the country -- larger than many nations’ sovereign wealth funds. Last week’s report by Stringer detailed $2.5 billion in payments from that pension fund to financial managers. The fees accompanied significant underperformance for retirees, led by hedge funds and private equity firms. Stringer’s report in turn led to a New York Times editorial saying that Stringer should “give city pensioners a clear, honest, easy-to-understand accounting of where the money goes, and to whom.”

The Times didn’t note that only a few months ago, Stringer was pushing Albany lawmakers to pass a bill that would have allowed an additional 10 percent of the city's $160 billion pension system -- or $16 billion -- to be invested in alternatives. Assuming the industry standard 2 percent management fee on such investments, that shift could have generated more than $300 million in new Wall Street fees every year.

Stringer championed the bill following a 2013 election campaign that saw him benefit from an influx of campaign contributions from financial executives after former Wall Street prosecutor (and former governor) Eliot Spitzer jumped into the race for comptroller. During the campaign, Stringer declared that he wanted the city to consider moving more pension money out of low-risk bonds and into Wall Street firms.

Upon taking office in 2014, he argued that the existing law prohibiting more than a quarter of the city's pension fund from being invested in alternatives was too restrictive.

"The current 25 percent limit on alternative investments prevents the city pension funds from creating an optimal investment portfolio,” Stringer's spokesperson told Pensions and Investments. "Increasing the basket will allow the pension boards to achieve a superior risk-adjusted return."

Unlikely Ally

The comptroller found an unlikely ally in his quest: the labor movement. While traditionally critical of Wall Street, union leaders in New York lobbied to get the bill passed. The United Federation of Teachers, considered to be among the most powerful unions in New York, told International Business Times it had lobbied to pass the bill.

The legislation also appeared to get an assist from the administration of newly elected Mayor de Blasio. Board meeting minutes from the New York City Teachers Retirement System indicate that while Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s appointees had been undecided on the bill, resistance from mayoral appointees dissipated when de Blasio took office.

De Blasio’s office declined a request for comment.

Many observers expected Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, to sign the final legislation because of his close connections to Wall Street donors. But Cuomo vetoed the Stringer-backed legislation, saying it "would undermine that balance by potentially exposing hard-earned pension savings to the increased risk and higher fees frequently associated with the class of investment assets permissible under this bill.”

Three months before issuing his report criticizing the high fees associated with alternative investments, Stringer's office said it would redouble its efforts to pass the vetoed legislation.

Former Securities and Exchange Commission attorney Ted Siedle said the comptroller’s insistence on exposing his city’s pension fund to higher-risk, higher-fee investments is concerning.

“For public funds, investing in high-cost, high-risk 'alternative investments' is highly problematic,” Siedle said. “My forensic investigations have revealed billions in undisclosed fees to private equity, hedge fund, and real estate firms. The lack of transparency is troubling, especially given that the SEC recently found widespread wrongdoing in the private equity industry.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.