Payday Loans: Study Highlights Default Rates, Overdrafts As Groups Debate CFPB Regulations

A lender makes a loan. Then a borrower pays it back. And to make sure that transaction doesn’t tank, there’s "underwriting:" verifying that the borrower will indeed be able to make the payments. This last step would be a key lesson from the subprime mortgage crisis.

But too often, federal regulators say, that step is missing from payday loans sold to the working poor, leading borrowers straight into a debt trap. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), last week, unveiled a proposal for new rules that would make loans more affordable by giving lenders a choice. They could gauge a borrower’s ability to pay before making the loan, or have the option of offering a capped number of loans to a borrower, with an exit strategy for loans that become too much to handle.

As the debate gets under way about how stringent final regulations should be, many consumer advocates are heavily in favor of option A, and don’t even want option B on the table, arguing that it’s easier to keep borrowers from entering a debt trap than it is to pull them out later on. A new study published Tuesday by the Center for Responsible Lending argues that early default rates demonstrate why upfront underwriting is the way to go.

“We need that ability to repay to be on the front end, from that first loan, because that’s when people are starting to default,” says Susanna Montezemolo, a senior policy researcher at the Center for Responsible Lending, and co-author of the report, “Payday Mayday: Visible and Invisible Payday Lending Defaults.”

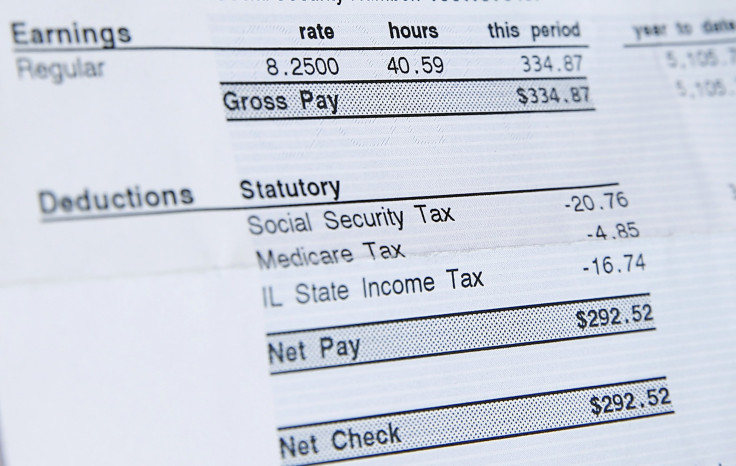

Payday loans are typically secured with either a post-dated check from the borrower, or by giving the lender access to the borrower’s bank account. As soon as a borrower gets paid at work, the lender is “first in line” to get paid on a loan that often comes with triple-digit interest.

“They time the payment when you’re most flush,” says Montezemolo. “Theoretically, payday default rates should be pretty low.”

However, that’s not what the center found. The report analyzed 1,065 borrowers in North Dakota who took out their first payday loans in 2011. The state allows borrowers to renew payday loans, and using a database of lending activity in the state, researchers were able to track the borrowers over time, and across different lenders from whom they may have borrowed. Nearly half of the payday borrowers -- 46 percent -- defaulted within two years. A third of the borrowers defaulted within six months.

Those findings are consistent with previous studies, the paper says, including a 2008 analysis by researchers at Vanderbilt University and the University of Pennsylvania. It showed a 54 percent default rate among payday loan borrowers in Texas within one year. Another study by the Center for Responsible Lending, in 2011, found a 44 percent default rate within two years in Oklahoma.

Perhaps more surprising to Montezemolo, then, wasn’t the high rate of default, but the timing of the defaults: among those who defaulted, nearly half did so on either their first loan (22 percent) or their second loan (26 percent).

Numbers like that raise the question -- if the default rate is so high, how could the business model last?

As it turns out, default doesn’t spell the end of paying the lender, or of taking out another payday loan: 66 percent of borrowers who defaulted still wound up repaying their entire debt. Nearly two in five (39 percent) of people who defaulted borrowed again later on.

So even though a default is financially stressful for the borrower -- “You don’t have enough money to pay it back on your actual payday,” Montezemolo says -- a default doesn’t appear to pose as much risk to the lender. Indeed, CFPB Director Richard Cordray, at field hearing last Thursday in Richmond, Virginia, said that many lenders rely on their "ability to collect" payments rather than on the customers' ability to repay loans, according to the bureau's research.

Looking at the repayment rate among defaulted borrowers in North Dakota, Montezemolo says, “I would suspect it has to do with debt collection activities, not your ability to repay the loans.”

The CFPB, for example, levied a $10 million enforcement action last year against the large payday lender ACE Cash Express, citing, in part, “illegal debt collection tactics -- including harassment and false threats of lawsuits or criminal prosecution -- to pressure overdue borrowers into taking out additional loans they could not afford."

Overdrafts from borrowers’ bank accounts also insulate lenders from defaults, according to the Center for Responsible Lending. Using a separate dataset of 52 payday borrowers, the study found that 33 percent experienced an overdraft on the same day they made a payday loan payment.

It’s what the researchers call an “invisible default," since it never shows up on the payday lender’s books. If not for overdrafts, serving to paper over defaults, the actual default rate would likely be higher, and would illustrate greater borrower distress, Montezemolo says.

The CFPB will soon convene talks with small business leaders who would be affected by the proposed rules, and the agency has said it will continue to solicit feedback from the public as it drafts the regulations. Eventually, a formal public comment period would follow.

The bureau's proposal has already drawn loud criticism from industry representatives who say the rules would be too stringent, and would choke off access to credit. But the CFPB has also drawn some unlikely supporters.

Ward Scull III, who runs a moving company out of Newport News, Virginia, says he's "typically a conservative Republican" and "free-market kind of person." Yet he views payday lending as a workforce development issue that keeps employees mired in debt, and inhibits money from flowing through the state economy. In 2007, he co-founded Virginians Against Payday Loans to champion state reforms.

Now that federal regulations are in play, Scull says, "I never thought I'd be excited to see the federal government stand up and do something."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.