Polar Bears: Arctic Ice Melt Affects All 19 Subpopulations

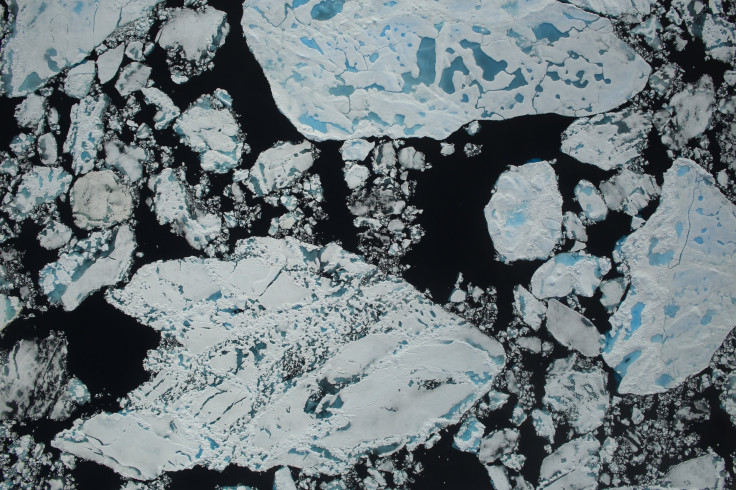

Arctic ice is melting under the onslaught of climate change: fact; polar bears, the largest terrestrial carnivores on the planet, are a vulnerable species: also a fact. And when you account for the animals’ dependence on Arctic ice for much of their essential activities, it is no surprise that the reducing ice surfaces in their native habitat poses them great risk.

A new study published Wednesday “finds a trend toward earlier sea ice melt in the spring and later ice growth in the fall across all 19 polar bear populations, which can negatively impact the feeding and breeding capabilities of the bears.”

The International Union for Conservation of Nature recognizes 19 subpopulations of polar bears (scientific name Ursus maritimus), all of which “live throughout the ice-covered waters of the circumpolar Arctic.” While listing the bears as a vulnerable species, IUCN says in its Red List: “Loss of Arctic sea ice due to climate change is the most serious threat to polar bears throughout their circumpolar range.”

So why is sea ice so important to these animals? Polar bears live mainly on a diet of seals, but since they can’t swim faster than their prey, they perch on ice platforms and hunt the seals by ambushing them at breathing holes. They sometimes also prey on seals resting on the ice. However, they can’t hunt seals in the absence of ice.

Kristin Laidre from Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and co-author of the study said in a statement: “Sea ice really is their platform for life. They are capable of existing on land for part of the year, but the sea ice is where they obtain their main prey.”

The study, titled “Sea-ice indicators of polar bear habitat,” was published in the journal the Cryosphere. Laidre and Harry Stern from University of Washington, Seattle, used satellite data from NASA for the last 35 years. It is the first paper “to quantify the sea ice changes in each polar bear subpopulation across the entire Arctic region using metrics that are specifically relevant to polar bear biology.”

Speaking of the methodology, Stern said in the statement: “We have used the same metric across all of the polar bear subpopulations in the Arctic so we can compare and contrast, for example, the Hudson Bay region with the Baffin Bay region using the same metric.”

The researchers saw a trend across all 19 polar bear subpopulation regions for the ice to melt earlier in the spring and freeze later in the fall.

According to Laidre, “These spring and fall transitions ... are also tied to the breeding season when bears find mates, and when females come out of their maternity dens with very small cubs and haven’t eaten for months.”

The study found an approximate three-and-a-half-week shift in both spring melt and fall freeze, which adds up to about “seven weeks of total loss of good sea ice habitat for polar bears” in the 35 years for which satellite data was available.

Stern said: “We expect that if the trends continue, compared with today, polar bears will experience another six to seven weeks of ice-free periods by mid-century.” He added that the trend does not seem to be accelerating and was linear. The researchers also plan to update their analysis annually with fresh data as it becomes available.

The study was funded by NASA and Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.