Did Gov. Susana Martinez Break SEC Rules In New Mexico Pension Deals?

When federal regulators in 2010 instituted new ethics rules to prevent Wall Street executives from using campaign contributions to influence government investments, they pointed to New Mexico as an example of a state mired in pay-to-play practices. Just after those rules were enacted -- with New Mexico still reeling from an influence-peddling scandal involving state investments -- voters elected a new Republican governor promising a swift crackdown.

“Corruption is a crime, not an ethical dilemma,” declared Gov. Susana Martinez in her first state of the state address. “Those guilty of corruption are criminals and they should be treated as such. First, we must institute criminal penalties for public officials who know about, but fail to report, pay-to-play activity. Public officials don’t have the luxury of turning a blind eye.”

And yet as the Republican’s second term in office draws to a close, an IBT/MapLight investigation shows that when it comes to campaign cash from managers of state investments, Martinez turned a blind eye to the ethical standards she championed. During her tenure, New Mexico has been giving lucrative investment deals to financial firms whose executives have delivered big campaign donations to Martinez and to groups that have supported her election campaigns -- a situation that may have violated the very pay-to-play rules that were passed in the wake of New Mexico’s previous scandals.

Under Martinez, two state funds managing more than $33 billion have shifted more money into higher-risk investments -- resulting in below-average returns, but generating at least $729 million worth of fees in just the last four years. Amid that shift, New Mexico committed at least $757 million to eight financial firms while donors linked to those firms have collectively given more than $1.2 million to Martinez and political groups supporting her.

Martinez’s office did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In some cases, New Mexico investments flowed to firms whose top officials gave directly to Martinez -- even though the Securities and Exchange Commission’s pay-to-play rule aims to prevent such donations. Some investments went to donors to the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC) -- which delivered money to Martinez-linked super PACs. Other investments went to donors to the Republican Governors Association (RGA), which Martinez chaired after it spent $2.5 million in New Mexico to boost her campaigns. RGA donors whose firms got investment deals include Wilbur Ross, who is now the U.S. Commerce secretary, and Republican megadonor Harlan Crow.

The SEC’s 2010 pay-to-play rule was designed to prevent any relationship between campaign donations and investment decisions. It bars financial firms from being paid fees for managing public money for two years if the firms or their executives donate to officials -- such as Martinez -- who serve on or appoint members of public investment boards. New Mexico also has a separate state pay-to-play law designed to restrict donations by companies as they bid on and negotiate state contracts.

“These funds are huge piles of money and the fees that investment advisers can earn are enormous, which is part of why these pay-to-play rules were put in place,” said Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, a Stetson University law professor who has studied the SEC’s donation rule. “You want the investment decisions made by the fund adviser to be market-based and not based on attempts to curry favor with whoever happens to be in the governor’s mansion.”

When they wrote the rule, SEC officials said contributions to “independent expenditure” groups would not be covered. However, the rule includes provisions intended to prevent financial firms from circumventing the prohibitions by routing campaign cash through third parties.

The SEC declined to answer IBT/MapLight questions about the situation in New Mexico.

The SEC rule has not deterred the RGA and RSLC from raking in money from financial firms and then bankrolling public officials who influence investment decisions. While the groups openly touted their spending on specific state races, spokesmen for the two organizations told IBT/MapLight that they do not allow donors to tell them how their contributions must be spent.

In response to questions about the donations to Martinez, the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board’s (NMERB) general counsel, Rod Ventura, told IBT/MapLight that state pension officials are not required to follow the SEC’s pay-to-play rule -- because, he argued, the rule only restricts the investment firms, not the pension funds.

“Those rules, to the extent that they are out there, don’t apply to us,” Ventura said, adding that “the majority [of the firms] haven’t made any political contributions.”

In light of the new revelations about investment deals going to donors, State Auditor Tim Keller, a Democrat, told IBT/MapLight that New Mexico should pass legislation to close a “gaping huge loophole” by applying the state’s pay-to-play prohibitions to contributions to groups that support candidates.

“Our law should cover direct contractors and political groups that are relevant to the contract at hand -- and that would certainly include governors associations, congressional committees and different interest groups that are explicitly politically affiliated,” said Keller, whose August report found that state agencies under Martinez have not been adequately complying with campaign finance disclosure laws.

“Political Influence Should Not Dictate Investment Decisions”

Over the last decade, state and local pension funds across the country have expanded their investments in private equity, hedge funds, real estate and other so-called “alternative investments.” In many cases, those investments -- whose details are often shrouded in secrecy -- have generated huge fees for Wall Street firms but have delivered weak returns for taxpayers and pensioners. While alternative investment firms argue that their offerings diversify portfolios and provide less volatile returns than traditional stocks and bonds, critics like Warren Buffett have derided the investments’ high costs -- and the SEC warned in 2014 that it found “ violations of law or material weaknesses in controls” in more than half of private equity investments it surveyed.

New Mexico is an example of the investment trends. The NMERB -- whose board includes three seats for gubernatorial appointees -- manages a $12 billion pension fund for more than 100,000 current and retired educators. When Martinez won office in 2010, less than a quarter of the fund’s assets were in alternative investments. During Martinez’s tenure, that share rose to almost a third of the portfolio, and New Mexico officials said last year they want to have 40 percent in alternatives -- more than double the average for major public pension systems.

A similar story unfolded at the State Investment Council (SIC), which Martinez chairs and which oversees a $21 billion endowment funded by taxes, leases, and royalties from oil and gas production. State records show that since Martinez became chair of the council, the SIC has increased its investments in various high-fee alternative investment classes, while decreasing its investments in traditional stocks.

“This strategy shift away from equity volatility toward income-generating assets has been years in the execution,” SIC spokesman Charles Wollman told IBT/MapLight. “There is significant history and very-well documented process behind this investment strategy shift.”

During her governorship, Martinez has worked to preserve her power over state investment funds’ financial decisions -- and to loosen restrictions on high-risk investments.

In the aftermath of the state’s previous pay-to-play scandals, Martinez in 2011 vetoed bipartisan legislation to remove her seat on the SIC. In 2016, while she was serving as the national chairwoman for the RGA, Martinez signed a Republican bill giving the SIC more latitude to invest state money in Wall Street’s alternative investment firms.

As New Mexico investment funds have poured more and more money into the Wall Street firms, returns have lagged. Over the last five years, NMERB has reported an average 8.7 percent annual return, while the SIC has reported a 9 percent average annual return.

By comparison, in the same time period, the average annual return was 14.6 percent for the S&P 500, 10.8 percent for a traditional index fund comprised of 70 percent stocks and 30 percent bonds, and 9.3 percent for the typical large public pension plan, according to investment analysis firm Wilshire. The underperformance means New Mexico retirees and taxpayers missed out on billions of dollars of investment gains.

“New Mexico is learning the hard way that the siren song of high-fee alternatives hasn’t panned out,” said Jeff Hooke, a former investment banker who is now a Johns Hopkins University finance professor. “New Mexico followed its peers onto the conga line, but the statistics show that beneficiaries would have been better off with simple indexes.”

New Mexico taxpayers and retirees have shelled out big money to financial firms for the weaker returns. From 2013-2016, NMERB reported paying more than $540 million in investment fees. The SIC -- which only began disclosing the total amount of fees it paid to investment advisers in 2016 -- reported paying $189 million in fees in a single year. As a percentage of total assets, the annual fee rates rank among the highest of any public investment fund in the country, according to Hooke’s research for the Maryland Public Policy Institute.

The neighboring public pension fund in Republican-run Nevada, which invests far less in alternatives, has reported 9.5 percent average annual returns over the last 5 years -- solidly outpacing the New Mexico funds. Meanwhile, between 2013 and 2016, Nevada reported paying a combined total of just $167 million in fees -- far less than New Mexico’s funds, even though the Nevada system is larger.

“Pickens And His Organization Have Made Campaign Contributions To Susana Martinez”

IBT/MapLight’s review of state investments and campaign finance records found that as New Mexico began shifting more money into alternatives, three firms linked to Martinez donors received more than $182 million worth of state investments. Some of the donations flowed to Martinez around the same time that the investments were made.

For instance, in March 2015, NMERB committed $37.5 million to EnerVest, a private equity firm that recently made headlines when one of its $2 billion funds lost all of its value due to bad bets on oil and gas. Prior to New Mexico’s investment, EnerVest and its top executive, John Walker, steered more than $61,000 to Martinez-linked groups. The haul included $5,200 direct to Martinez’s campaign and $10,000 to Advance New Mexico Now, a pro-Martinez super PAC, in the year before the state’s investment.

The EnerVest PAC also delivered $10,000 to U.S. Rep. Steve Pearce as he glided to reelection in 2016 -- and soon after launched a gubernatorial bid for the GOP nomination to succeed the term-limited Martinez. Pearce plans to finance a 2018 campaign with help from his congressional campaign war chest.

In July of 2012, Dallas real estate scion Harlan Crow’s company gave $50,000 to the RGA -- which at the time counted Martinez as one of its executive board members. Months later, Crow appeared before the NMERB’s board to personally pitch officials on investing pensioners’ savings in his real estate fund. The board approved a $50 million investment.

In late 2013, Crow’s mother, Margaret, donated $10,400 to Martinez’s campaign. Crow Holdings followed up with a $100,000 check to the RGA, which was then supporting Martinez’s 2014 reelection bid. In the closing months of the election, NMERB approved a separate $35 million investment in another Crow Holdings fund. In 2016, while Martinez was chairing the RGA, Crow Holdings gave the organization an additional $100,000. That same year, NMERB approved a $30 million investment in another Crow fund, bringing the pension fund’s total investment in Crow funds to $115 million.

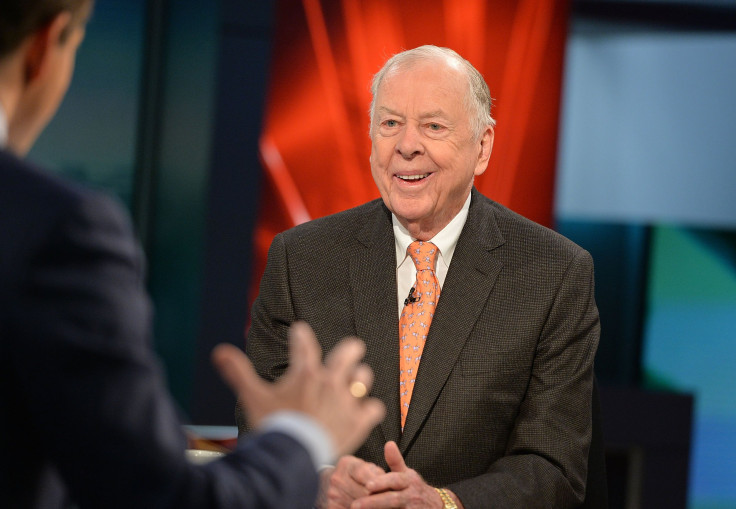

Meanwhile, in November 2013, T. Boone Pickens gave Martinez $10,400. A year and a half later, NMERB approved a $30 million commitment to Pickens’ energy investment firm, BP Capital. According to meeting minutes of the investment deliberations, pension officials were told that “Pickens and his organization have made campaign contributions to Susana Martinez, but the BP Capital Partners individual team members have not.” However, pension overseers were also told that Pickens would own 50 percent of management’s portion of the fund.

In the case of EnerVest, Crow and Pickens, donations directly to Martinez and Advance New Mexico Now were made within two years of the state committing to invest in the financial firms, as were six donations from Crow to the RGA. The SEC’s rule requires a two-year “cooling off” period between donations and firms earning fees from state investments.

EnerVest and Crow did not respond to requests for comment.

A spokesperson for BP Capital told IBT/MapLight: "BP Natural Gas Opportunity Partners was aware of the SEC's 'pay to play' rules and its obligations under the rules prior to NMERB’s commitment to the Fund. The Fund had at the time (and continues to have) appropriate compliance policies and procedures to avoid violations of this and other SEC rules."

The firm additionally stated that BP Capital "did not accept NMERB's commitment to the Fund until November of 2015, after the two-year 'cooling off' period in the pay to play rules had expired. In addition, the Fund did not charge NMERB any fees or carried interest with respect to any part of that 'cooling off' period."

Pension officials were made aware of some of the donations by NMERB portfolio manager Mark Canavan, who was at the agency during a 2006 pay-to-play scandal. According to court records, Canavan admitted that he let politically connected brokers see bid information before awarding state contracts -- and that he lied to federal investigators about one such case.

While Canavan informed board members of some donations to Martinez and Martinez-linked super PACs, he nonetheless recommended approval of the investments -- and board members agreed.

NMERB officials do not publish the fees paid to individual managers, including EnerVest, Crow Holdings and BP Capital. They asserted that the governor’s appointed board members do not find or present investment opportunities, and therefore donations do not influence investment decisions.

“Whether somebody makes a campaign contribution or not is not a part of our investment process,” NMERB chief investment officer Bob Jacksha told IBT. “We are after the best balance of risk and return, the best manager in the space we can get, and the best performance.”

Other RGA Donors Also Received New Mexico Investments

Under New Mexico law, prospective NMERB investment managers are required to complete a form disclosing their campaign donations. The form says it covers donations directly to statewide officials, to any “political committee that is intended to aid or promote” the election of statewide officials if that committee is controlled by those officials or their agents.

While direct donations to Martinez and Martinez-linked super PACs were disclosed, NMERB officials told IBT/MapLight they didn’t believe investment managers had to report contributions to groups like the RGA that aren’t controlled by a single candidate. The RGA works on behalf of Republican gubernatorial candidates nationwide, but Martinez has been part of the group’s leadership since she was first elected governor.

“The question is whether contributions were made to a committee ‘controlled’ by an applicable public official,” Ventura, the NMERB’s general counsel, told IBT/MapLight in an email. “Although Governor Martinez was the chair of the RGA in 2015/2016, it is unlikely that she was the sole decision maker there.”

Campaign finance records independently reviewed by IBT/MapLight show that other RGA- and RSLC-linked donor firms received state investment contracts:

- Invesco -- The firm received a $150 million from the SIC in June 2015 -- less than a year after Wilbur Ross gave the RGA $150,000 during Martinez’s reelection campaign. Ross sold his firm, W.L. Ross & Co., to Invesco in 2006; he continued to lead the Invesco subsidiary until he became Trump’s commerce secretary this year. A Commerce Department spokesperson told IBT/MapLight that “Secretary Ross requested and received preclearance from the compliance department at Invesco” to make the RGA donation and that the RGA told Ross his donation would be used in a manner consistent with election laws.

- Apollo Global Management -- The firm received a $50 million investment from NMERB in 2013. The investment occurred after Apollo executive Josh Harris gave the RGA $25,000 in 2010 during Martinez’s first election run, and another $25,000 in 2012 while Martinez was on the RGA’s executive committee. New Mexico taxpayers have given Apollo more than $2.4 million in fees on the investment, according to state records. An Apollo spokesperson declined to answer IBT/MapLight’s questions about the donations.

- Macquarie Capital -- The Australian firm received $200 million worth of commitments from the SIC between 2014 and 2015. The firm and its affiliates have donated $200,000 to the RGA since 2011, including $50,000 last year while Martinez chaired the organization. In 2013, Macquarie Capital hired Public Opinion Strategies, a consulting firm whose partner, Nicole McCleskey, served as a senior advisor to Martinez’s 2014 reelection campaign. McCleskey’s husband, Jay, ran the pro-Martinez super PACs. In 2016, the SIC reported paying Macquarie $323,519 in fees. Macquarie declined to comment on the record.

- Prudential -- The firm received a $50 million NMERB investment in 2011. It received another $35 million NMERB investment during Martinez’s reelection campaign in 2014. During Martinez’s tenure, Prudential has given $200,000 to the RGA and another $50,000 to the RSLC -- organizations that funded the Martinez-linked super PACs.

- Bain Capital -- The firm received a $40 million NMERB investment in February 2014. Less than three weeks later, Bain’s founding partner, Robert White, gave $50,000 to the RGA, which was supporting Martinez’s reelection campaign. White remains a special limited partner at Bain, but a source familiar with the firm said he retired in 2002 and has no active role there. While Bain requires employees to seek approval from compliance officials before making political donations and bars them from giving to state or local candidates, the source said those guidelines don’t apply to White since he is not an active employee. Bain has been paid more than $1.2 million in fees by the NMERB. The firm received another $50 million NMERB investment in July.

In recent weeks, as New Mexico’s previous influence-peddling scandals continue to be litigated in court, a fight over secrecy has broken out at the investment council. Some panel members refused to sign a Martinez-backed ethics pledge that they said would bar them from disclosing details about their work to the public. At the same time, lawmakers voted to put a measure on the 2018 ballot that would create an independent ethics commission, and they have begun scrutinizing the fees being paid to Wall Street firms.

“If the goal is to stop pay-to-play, and make sure tax dollars are being invested fairly and not just to the highest political bidder, then all of these contributors need to be part of the rules,” Democratic Rep. Bill McCamley, who recently led a hearing on investment fees, told IBT/MapLight. “In a state with staggering unemployment, devastating poverty, and one of the lowest rates of child well-being, we need every dollar of public money to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. In this regard, Martinez has failed over, and over, and over again, and New Mexicans suffer while her friends get rich.”

Alex Kotch and Jay Cassano contributed reporting to this story.

Update at 4:36pm ET: This story was updated to include comment from BP Capital.

Update on October 6: The original version of this story said the State Investment Council had a 5-year average annual return of 7.7 percent. That was based on the most recent SIC data posted on its investment performance website and was the return as of March 31, 2017 . SIC has reported a more recent 5-year annual rate of return of 9 percent, as of 6/30/17. We have updated this story to reflect that more recent number.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.