Halliburton In Colorado: Board Member’s Donation Shows Power Of Oil And Gas Industry

A top fossil fuel industry official poured $40,000 into the Colorado Republican Party’s super PAC on the same day the state’s legislature began considering a bill to limit the oil and gas industry’s fracking and drilling near schools, according to state documents reviewed by International Business Times. Soon after the contribution from Halliburton board member J. Landis Martin, Republican lawmakers lined up against the legislation. They eventually killed it — days before a deadly blast at a home near an oil well in Northeastern Colorado.

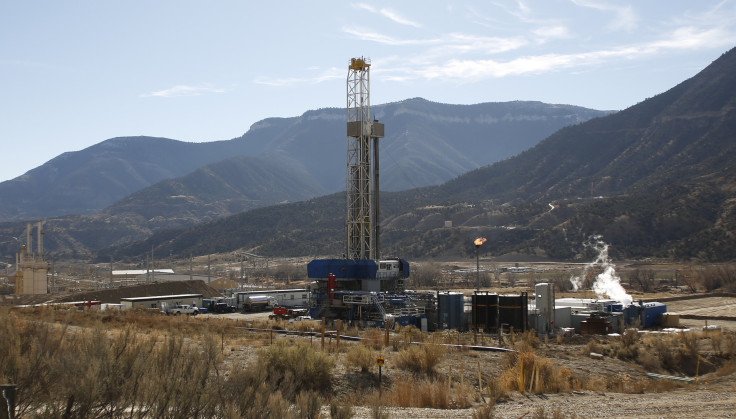

Halliburton has a large presence in Colorado. The company says it employs 1,900 people in operations across the state; it bankrolled a 2012 effort to defeat municipal fracking regulations in the state; and it has a top executive on the executive board of the Colorado Oil and Gas Association — an industry lobbying group that fought the setback legislation, according to state records. (Halliburton is a member of the COGA and has touted its links to the group in the past.)

Martin not only serves on Halliburton’s board, he is also chairman of a private equity firm that invests in a Colorado-based company that provides fracking materials to fossil fuel operations in the state and elsewhere.

Read: Oil And Gas Industry Power Builds Wells Near Schools In Colorado, Trumping Environmental Concerns

Martin’s March 14th donation was one of the single largest individual contributions in the Colorado Republican Party’s modern history, and the second largest ever given to the party’s super PAC, according to data from the National Institute on Money In State Politics.

Colorado is one of 29 states with campaign finance laws designed to discourage fundraising during legislative sessions. Martin’s contribution, however, appeared to legally flow around that statute because it went to the Colorado Republican Party’s independent expenditure committee, which supports legislators — but not directly to the legislators themselves.

Martin told IBT the donation was unrelated to the setback bill, which would have clarified that the 1,000 foot limit between schools and new oil and gas wells started at the edge of school property, not at school buildings themselves.

“I was totally unaware of that legislation,” Martin said. “I’ve never had any interest really in any Colorado legislation. Most of my businesses are outside of Colorado.”

When asked why he made the donation if he had no interest in Colorado politics, Martin replied: “I’m supportive of all Republican causes.” He also denied his political contribution had any connection to oil and gas interests.

“I don’t really follow the state legislature there,” said Martin, who is a prominent philanthropist in Colorado. He also told an interviewer in 2013 he moved to Denver in 1981.

Democratic Representative Mike Foote, who introduced the setback bill on March 14th, told IBT that while it is impossible to draw a direct connection between specific donations and GOP votes against his bill, the situation illustrates how the GOP’s fundraising strategy can influence its legislative agenda.

“It’s no secret that the oil and gas industry are big contributors to the Republican Party -- so this doesn’t surprise me,” he told IBT. “The oil and gas industry gives large sums of money to Republicans and for Republicans to then vote against what the oil and gas industry wants would not be not a good way to keep those contributions going.”

Scrutiny Of Oil And Gas Industry Intensifying After Explosion

Colorado’s oil and gas industry is facing intensifying scrutiny after an April 17th explosion at a Firestone home near an oil well owned by Anadarko. State investigators have connected the blast, which killed two people, to a faulty gas line. The deadly accident occurred just after Colorado Senate Republicans sided with oil and gas lobbyists and blocked the setback bill.

In the weeks after the explosion, Republicans again sided with oil and gas lobbyists, mounting opposition to two other initiatives. One measure which Senate Republicans blocked was “forced pooling” legislation designed to prevent oil and gas companies from forcing homeowners to allow fracking and drilling on their property.

Another measure that Republicans opposed — which is still pending — would compel oil and gas companies to disclose the location of their lines and wells to nearby homeowners.

Republican opposition to the oil and gas regulations came after a 2016 election in which fossil fuel industry donors delivered a combined $898,000 to the Colorado Republican Party and the fundraising groups for House and Senate Republicans.

That oil and gas money did not stop after the election — it continued to flow to the GOP in the leadup to the legislative session that has seen the Republican-controlled senate defeat proposals to more strictly regulate drilling and fracking.

Post-election campaign finance reports reviewed by IBT show that the Colorado Republican Party and the Senate Majority Fund — which supports Colorado Republican senators — has received $82,000 from oil and gas industry donors since December. Of that, $60,000 came after the legislature was in session. That included Martin’s $40,000 donation. Martin had previously made more than $48,000 worth of contributions in Colorado since 1996, according to data compiled by the nonpartisan National Institute on Money in State Politics.

“Trying To Influence Legislation Just For Personal Profit”

Since 1998, Martin has been a lead director at Halliburton, an oil and gas services conglomerate that has substantial business in Colorado -- and therefore a deep interest in shaping state regulations governing the fossil fuel industry. In 2011, Colorado’s Democratic governor John Hickenlooper drank some of Halliburton’s fracking fluid during a meeting with oil and gas representatives, presumably to prove the liquid’s safety. Jim Brown, Halliburton’s Western hemisphere president and a member of the COGA advisory board, according to the group’s 2017 membership materials, is listed under a Denver address on Halliburton’s website.

The website also lists Martin as the company’s lead director and a member of its Health, Safety and Environment committee. During Martin’s tenure at Halliburton, the company gave $30,000 to the campaign aimed at defeating Longmont’s proposal to more stringently regulate fracking, according to the trade publication Energy and Environment News.

While serving on Halliburton’s board, Martin is also the chairman of a Denver-based Platte River Equity, whose website says it invests in Wildcat Minerals. Platte River notes that Wildcat Minerals “ is a leading independent provider of transloading, distribution and logistics for oilfield consumables, primarily proppant, used in the hydraulic fracturing process.”

Colorado’s Fair Campaign Practices Act declares that “large campaign contributions to political candidates allow wealthy contributors and special interest groups to exercise a disproportionate level of influence over the political process” and that “large campaign contributions create the potential for corruption and the appearance of corruption.” The law prohibits lobbyists from donating to lawmakers during the legislative session.

While the Halliburton-linked Colorado Oil and Gas Association and American Petroleum Institute was lobbying to defeat the bill, Martin himself is not a registered lobbyist. Martin donated to a political party, which is effectively exempted from Colorado’s ethics law. The statute declares that the bill does not bar interest groups from fundraising for a political party “so long as the purpose of the event is not to raise money for specifically designated members of the general assembly.”

One watchdog group, though, said that although the contribution is legal, it is still problematic.

“It’s not common to see a contribution that’s so closely timed to legislative action like that,” Luis Toro, Director of Colorado Ethics Watch, told IBT. Ethics Watch has unsuccessfully argued in court that the Republican party’s independent expenditure committee should be subject to contribution limits. “It’s definitely a problem. You’ve got someone who’s acting under a profit motive trying to influence legislation just for personal profit, as opposed to the good of the people.”

Super PAC Has Faced Legal Troubles

Toro said Colorado laws governing donations during legislative sessions were not nearly strong enough.

“It’s almost window dressing because the lobbyists can make contributions before the session or the day after the session. And then other people can make contributions that are timed with legislation…It creates the appearance that legislation is being bought and paid for by campaign contributions.”

The super PAC, also called an independent expenditure committee, that Martin donated to has been plagued by legal issues since its inception in 2014. Super PACs are allowed to raise unlimited amount of funds from corporations, individuals and unions, but they aren’t allowed to coordinate directly with candidates or campaigns.The state GOP formed the Colorado Republican Party Independent Expenditure Committee to take advantage of the Citizens United Supreme Court decision that found limits on campaign contributions unconstitutional, and to keep pace with liberal super PACs, which outspent conservative counterparts in Colorado by nearly 150 to 1 in 2010.

The state’s Republican party went to court and secured the right to form an independent expenditure committee, a ruling that Colorado Ethics Watch challenged. Ultimately, an appeals court ruled in favor of the GOP, writing that the arrangement was legal so long as the party and the committee don’t coordinate spending and operations.

Tyler Harber, the operative who ran the super PAC, was the first person in the nation to be prosecuted for the kind of coordination between committee and party that the court forbade. Harber was the director of the super PAC during the 2014 election cycle before his contract was terminated after the 2014 election. In 2015, he pled guilty to coordinating spending between a 2012 Virginia congressional campaign and a super PAC. Harber told the court he believed what he had done was common practice, the Washington Post reported.

While super PACs are legal nationally, Colorado politicians have tried to make them illegal in the state. Just a day after the setback legislation was introduced, Democrat Rep. Mike Weissman introduced a bill in the House that would have made independent expenditure committees illegal. The bill passed the Democratic-controlled House, but died in a committee in the Senate, where Republicans hold the majority.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.