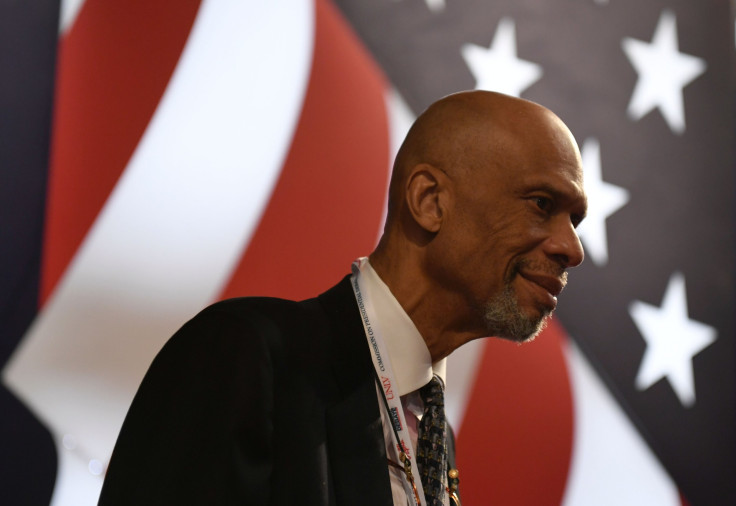

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Compares NFL Protests To American Revolution, Conservatives To British

Weighing in on the simmering debate over football players kneeling during the national anthem, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar slammed President Trump and those who have criticized high-paid players for their apparent lack of gratitude.

“That’s pretty much what the British said about the leaders of the American Revolution — the wealthy were making money by colluding with the British, so they should just be grateful. Fortunately, those leaders couldn’t be bought off,” Abdul-Jabbar said.

“The implication here is that black athletes should be grateful that they’ve been invited to dine with the white elites and if they want to keep their place at the table, they should keep dancing and smiling and keep their mouths shut. The myth of the Happy Negro needs to be dispelled once and for all.”

In two interviews with International Business Times, the NBA legend said that he is encouraged that athletes are unifying in protest against racism that is “getting worse under the current administration” and against “the attempt to curtail the First Amendment by a rich, entitled white man who thinks only he should be allowed to speak freely.”

Responding to IBT questions on Sept. 26, after a weekend in which the NFL protests had accelerated, Abdul-Jabbar praised the now-unemployed quarterback who started the “Take the Knee” movement a year ago.

“It’s to Colin Kaepernick’s credit that he was willing to protest institutional racism when he was almost alone and without much power,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “His goal was to make America aware that there is an underlying racism present and that we need to address it. President Trump’s statements at Charlottesville and about the NFL proved to many Americans that Colin was right. It’s a testament to the bravery and commitment of all those other players, coaches, and owners across all sports who have joined in the protest.”

The former Lakers center — who remains the league’s all-time leading scorer — is no stranger to protest. He attended the famous “Ali Summit,” in which he and other high-profile athletes stood in solidarity with Muhammed Ali as the boxer refused to be drafted into the Vietnam War. He also boycotted the 1968 Olympics. In recent years, he has written books and columns about political issues — and has publicly tangled with Trump. During the presidential campaign, Trump sent Abdul-Jabbar a handwritten note slamming a column he wrote in the Washington Post.

Abdul-Jabbar denounced Trump for saying protesting athletes should be fired.

“I can think of instances when a president’s opinion could be worthwhile, especially when trying to uphold principles of the Constitution or the well-being of the players,” Abdul-Jabbar told IBT. “However, Trump’s comments are direct attacks on the constitutional principles of free speech. For someone who has sworn to uphold the Constitution, this is either an example of immense ignorance or willful treason.”

But asked whether sports team owners should be allowed to fire players for speaking out on political issues, Abdul-Jabbar acknowledged owners’ potential concerns.

“Sports teams are a business and business owners have the right to punish players who the owners think might be harming their business,” Abdul-Jabbar told IBT. “There is a risk when a player chooses to protest. Hopefully, the owners will take into consideration what is being protested and the passive, non-violent method of protest.

“Two things are being protested right now. The original issue of systemic racism is still around and getting worse under the current administration. But the second issue that has brought so many athletes together is the attempt to curtail the First Amendment by a rich, entitled white man who thinks only he should be allowed to speak freely.”

Abdul-Jabbar also addressed the issue of white privilege, responding to a quote from Spurs coach Gregg Popovich, who recently said: “Race is the elephant in the room, and we all understand that unless it is talked about constantly, it is not going to get better. ... People have to be made to feel uncomfortable; especially white people. We still have no clue of what being born white means.”

“Coach Popovich is absolutely right and he stated it eloquently,” Abdul-Jabbar told IBT. “Many white Americans are aware that white privilege is embedded in American society and are eager to fix this disparity. Others have been affected negatively by the economy so it’s hard to see how they have any privilege when they are struggling so much. Naturally, it angers them to be told they have an advantage yet still are fighting for survival. It’s like blaming them for not being more successful.

“However, this understandable resistance to the facts can be overcome by a consistent and persistent effort to educated open-minded people. This is difficult because systemic racism seems hidden and therefore easily overlooked. But it isn’t hidden to those suffering from it. By exposing it — which these protests by athletes are trying to do — we have hope of overcoming it. Seeing all these athletes, coaches, and players across the different sports kneeling together and locking arms gives me more hope than I’ve felt for a while.”

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of IBT’s Sept. 7 discussion with Abdul-Jabbar, who has just published a book about his college experience as well as a graphic novel about the brother of Sherlock Holmes. Podcast subscribers can click here for the full conversation.

How did you first become politically aware and engaged? What turned you into a political activist?

For me, it started with the murder of Emmett Till. I was in the third grade when that happened. I didn't understand it. I saw his picture in Jet magazine, when his mother exposed his body to show what had happened to him. I thought it was horrible. I asked my parents about it and they really didn't have the words to explain it. It bothered me a lot.

I started paying attention to what was going on racially in our country. I kept silent about it, but it troubled me each year of my life at that time while I was in grade school. Things were happening because the civil rights movement was gaining more momentum. I got drawn into it that way, but the one incident that really was the critical moment for me was the murder of Emmett Till.

When you decided not to go to the Olympic Games, sports announcer Joe Garagiola suggested that you should leave the country. How did that feel? Do you think the same hostility to protests and dissent exists today?

I think Mr. Garagiola was voicing the sentiments of most conservative people because America was just great for them. But for a Black American, we had to put up with people being murdered and denied the most basic rights: the right to vote, the right to go into a restaurant and order a meal. These are very fundamental things. We had to use separate bathrooms. I got a chance to see all of that up close and personal. I didn't like it. I wanted it to change. I was voicing the feelings of almost every Black American at that time.

Do you think there is more tolerance for dissent and protest today than there was when you were a young man?

There's still a pushback. I don't think the pushback is as vigorous as it once was because people have seen now and understand the negative side of Jim Crow and racist attitudes, what they end up with. They see how ugly it is.

The national response to what happened in Charlottesville, I thought, that was heartening to me because Americans of all stripes saw it for what it was. It was ugly. It is un-American. It is not what we are about. We don't like it. We don't want to see that. The response to the president's trying to equivocate on that issue was, for me, it was very encouraging because it shows me that most Americans understand what the issues are and are supportive of treating everybody the same way.

Your new book, “Coach Wooden and Me,” describes your political activism as a college student. Was Coach Wooden supportive of your participation in the civil rights movement?

Coach Wooden was very understanding about my need to do something as an activist because he was with me. If you read the book, you saw the incident where the woman referred to me as the N-word. The classic example of the elderly, gray-haired lady and how she referred to me. Coach Wooden, he really didn't understand that Black Americans had to deal with that every day of their lives. He saw just the incidents that I had to deal with at various times while he was in the vicinity. It really gave him a better understanding of what life was like. He couldn't condemn my need to do something about it because he saw how horrible it was up close and personal.

In a 2015 article for Al Jazeera, you described your conversion to Islam in the 1970s. You wrote about Christianity: “I found it hard to align myself with the cultural institutions that had turned a blind eye to such outrageous behavior in direct violation of their most sacred beliefs.” Some look at terrorism committed in the name of Islam and argue that Islam as an institution is either condoning those atrocities or turning a blind eye to them. What do you say to that?

That's not correct. The people that are doing those atrocities, they don't care what people think. The Muslims that do care and that do understand that those things are outrageous, they speak up on it. The world at large doesn't really listen to them. They just take that for granted and say, “Well, what about these other people?” There's nothing that sane and civilized Muslims can do to stop the people that are in ISIS. That has to be done by armies. They're burdening innocent Muslims with the sins of fanatics and murderers. That's not the way to deal with it.

During your NBA career in the 1970s and 1980s, was there pressure on you to keep quiet about political issues?

I think that things more or less got quiet with regard to a lot of the issues that were important to me. But more recently, things have gotten to a point, look at Ferguson and issues like that. So many young black men being killed by police officers. This is not a new story. People are finally, because of the overwhelming presence of cellphones, we're finally getting a valid idea of what young black men go through in dealing the police sometimes. It's pretty scary if you're a young black guy out there. Some of these issues that come up are valid and need to be addressed. I think the reaction from the black community deals with the incidents of the time, of this era. These are things that have to be solved, these problems.

What do you think has most changed in race relations since the height of the civil rights movement?

I think that what's changed is that the basic awareness of the evils of bigotry are a lot more obvious to the average American right now. I think that is a great accomplishment. People understood what was wrong with seeing Nazis march in Charlottesville. That little parade that they did in front of the Jewish synagogue, that was really frightening. It looked like Kristallnacht or something.

People don't want to see that here in America. People are aware of what that can lead to. I think that the response that I saw there from just average Americans really heartened me that we can win the battle for minds and hearts because people don't want that in America. We've got to build on that sentiment, and make sure that people understand what's at stake here, and that they do the right thing.

There's a “shut up and play” or "shut up and sing" idea out there that athletes and entertainers should refrain from speaking out on political issues. Do you agree or disagree?

My response to that is people don't have a choice as to when they need to speak out. When they see something where you have Nazis marching in the street with torches, it's time to do something and say something. It can't be seen as an inconvenient time. Those things need to be confronted immediately.

Any concession that people want to make — "It's not convenient for my branding" — we can't go with that. Certain things need to be fought as soon as they present themselves and they need to be confronted. I have nothing but respect for the people that understand that and took the opportunity. All those CEOs that left the president's commission after what he said about Charlottesville, that, to me, was a prime indication of where we're at as a nation. I'm encouraged by that.

There seems to be right now a debate inside the Democratic Party over so-called identity politics versus economic-class politics. Can we separate race and economic class as distinct issues?

I think that race really is not as important an issue. Once people stop discriminating on the basis of race, it has no meaning. What we should be about is giving people the means to contribute to society in whatever way that they learn. What a person has to offer should be judged on what they give to society. Their ethnicity, or religious background, or any of those issues, they are secondary. As Dr. King said, it's about the content of people's character and what they have to offer society. I think judging people based on those issues will enable us to have the meritocracy that America is supposed to be.

What are you most pessimistic about, and what are you most optimistic about?

I'm pessimistic about the reaction to global climate change. It's a real thing. It's creating problems. People had better wake up. That really bothers me. I think that we are increasingly becoming aware of the fact that everybody on this planet is connected and we have to understand that and do the things that we can to make the world a better place. That still should be our number one focus.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.