Red Planet Blues: India To Launch Mars Space Mission In October, But Some Question Priorities

India will launch its first space mission to Mars in October, according to President Pranab Mukherjee, as the South Asian giant joins rivals U.S., Russia, Japan and China in the race to the red planet.

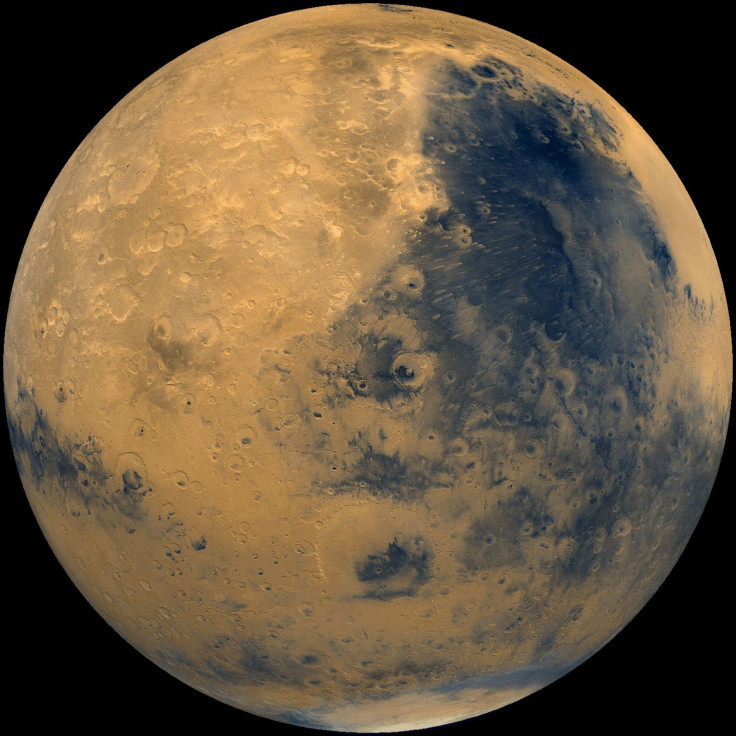

At a cost of some 4.5 billion rupees ($83 million), India will send an unmanned space vehicle to orbit Mars, Reuters reported. The craft, which will be manufactured completely in India, will take nine months to reach the planet and then enter into an orbit about 310 miles from the surface in order to collect data on its climate and geology.

An Indian space official told Indian media that methane sensors will be used to predict the possibility of life on the planet.

"The mission is ready to roll," Deviprasad Karnik, a scientist from the India Space Research Organisation, or ISRO, told Reuters from Bangalore.

President Mukherjee told parliament in New Delhi that several space missions are planned for 2013, including the “launch of our first navigational satellite."

“The space program epitomizes India’s scientific achievements and benefits the country in a number of areas,” Mukherjee said.

India’s space program is more than 50 years old. Five years ago, the Chandrayaan satellite found evidence of water on the moon (where India seeks to land a wheeled rover by 2014).

"There is no provision in the current [Indian] Mars program for a vessel to land on the planet,” Karnik told the Wall Street Journal.

The Indian space agency will conduct a total of 10 space missions by November, at a cost of about $1.3 billion.

However, some critics charge that the Indian government should spend its money to fight malnutrition, tackle widespread poverty, provide safe and clean drinking water and fix infrastructure on terra firma rather than take trips to other planets.

The blackout, which turned out the lights for some 600 million people last year and represented the biggest power outage in human history, symbolized the country’s crumbling energy infrastructure and desperate need for upgrades.

"I don't understand the importance of India sending a space mission to Mars when half of its children are undernourished and half of all Indian families have no access to sanitation,” Jean Drèze, a development economist at the Delhi School of Economics, complained to the Financial Times.

He suggested that the space mission is "part of the Indian elite's delusional quest for superpower status."

Last August, an editorial in Times of India, cautioned that India’s space ambitions should have pragmatic and realistic objectives, rather than reflect a “false sense of national pride."

"More attention needs to be paid to the poor on issues such as health, drinking water and literacy," Bindeshwar Pathak, a prominent welfare activist, told Agence France Presse. "Going to space might have some scientific benefits, but it alone will not help the condition of India's poor."

According to the World Bank, one-third of Indians live below the poverty line, while the U.N. said that one-third of the world’s malnourished children live in India.

Krishan Lal, president of the Indian National Science Academy, commented on the relative strangeness of India seeking to explore Mars.

“India is a country which works on different levels. On the one hand, we have a space mission; on the other hand, a large number of bullock carts,” he said. “You can’t, say, remove all the bullock carts, then move into space. You have to move forward in all directions.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.