RFRA Indy Star Cover Shows Enduring Power Of The Front Page In Age Of Social News

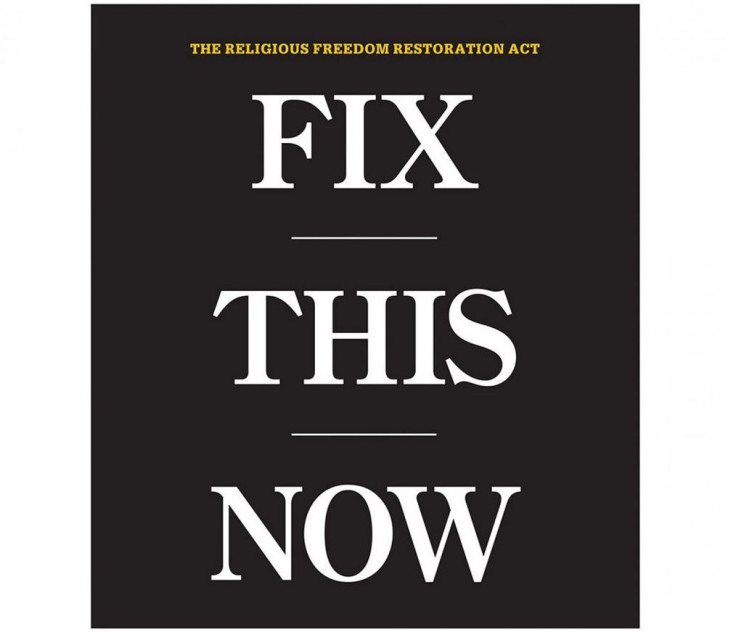

The most high impact news image of the day originated on one of journalism’s oldest surfaces. Tuesday’s cover of the Indianapolis Star, which featured nothing but the words “Fix This Now,” took off across the news business Tuesday, not just taking over social media but serving as a topic of conversation on TV and radio as controversy surrounding the recently signed Religious Freedom and Restoration Act, or RFRA, continued to escalate in Indiana.

“I think that will turn out to be an iconic headline and really important in this debate,” said Tim McGuire, the Frank Russell Chair for the Business of Journalism at Arizona State University’s Cronkite School of Journalism. “The front page of a newspaper carries a special kind of impact.”

The cover served as the headline for an editorial the Star published calling for an overhaul of the act, which its detractors have framed as a way for private businesses to discriminate against people on the basis of sexual orientation. Indiana Governor Mike Pence has disputed that interpretation aggressively since signing the bill into law last week.

Technically, the cover was making waves before it hit Indianapolis’s streets. On Monday evening, a handful of Indianapolis Star staffers, including editor Karen Ferguson, tweeted out pictures of the cover. “It’s this important,” Ferguson wrote.

Ferguson’s tweet, which was favorited or retweeted more than 1,500 times, was picked up by a number of her more socially connected followers, and by day’s end, the cover had been discussed on American television more than 120 times, including on SportsCenter, The Ellen Show and CBS This Morning, according to research from media monitoring firm Critical Mention. That same research found that it was mentioned an additional 12 times on Canadian broadcasts, 40 times on U.S. radio broadcasts, and in 67 online news outlets.

'An Unusual Position'

Though the backlash had become a national story, nobody was more surprised by the reaction than the Star, which saw many of its top staff on the other side of cameras and microphones discussing the cover. "It was an unusual position for us to be in," Indianapolis Star opinions editor Tim Swarens said. "We don't have CNN and the BBC calling us routinely."

Swarens noted that the Star has just three people working on social media full time and no one on staff in charge of public relations. Swarens said he and his colleagues spent most of their time thinking about how to spread the editorial's text on social media. Devising a strategy for sharing the cover did not occur to them. "What was interesting to us was that print page had such a big impact," Swarens said.

Though newspapers have been in decline for over a decade, Tuesday’s events point to the enduring mystique and relevance of their covers. “It's got a historic, iconic kind of base that we know in our bones,” McGuire said of a newspaper cover. “There is still something very powerful about the front page and the statement it can make.”

Part of the novelty came from the fact that newspaper editors typically do not distrupt standard layouts familiar with readers. “Most newspapers have been incredibly judicious about the way they've used that real estate,” McGuire said.

Whether it’s because of legacy or tangibility or something else entirely, it is hard to imagine a piece of digital real estate that’s analogous. Website homepages change every few minutes, or sometimes depending on who is accessing the page, and on what kind of device. Users, McGuire said, grasp that. “It is pretty impossible to imagine using the cover of one's webpage could have the same impact,” hee said.

Struggling Homepages

Changing economics play a role there, too. As more and more news consumers gather information via social streams like their Facebook and Twitter feeds, fewer and fewer people are making their way to publishers’ homepages. Traffic to the New York Times website, for example, has fallen by 50 percent in the past two years, and there are few reasons to suspect this trend will reverse itself.

Indeed, as more of the platforms that deliver news look to swallow up the publishers who depend on them, newer publishers like Reported.ly, NowThis News and Buzzfeed are simply dispensing with digital destinations altogether. Those moves allow publishers to be where audiences are, and to gather impressions on a scale that journalism analyst described as astronomical. But that move also contributes to the ephemerality of news, something that is less likely to endure as a symbol of change.

Tuesday’s cover has that chance. At the end of Tuesday, Pence had said he wanted a bill on his desk showing that nobody can be discriminated against by week’s end.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.