Rhode Island Has Lost $372 Million As State Shifted Pension Cash to Wall Street

As Rhode Island General Treasurer Gina Raimondo promotes her 2014 gubernatorial campaign, she touts her supposed success in putting her state’s pension fund on firmer financial ground. That message has helped Raimondo surge to a lead in the polls, as reported by WPRI. What she fails to mention, though, is that the returns from her investment strategy have been far less beneficial for state pensioners than for the Wall Street firms now managing a growing share of Rhode Island’s money.

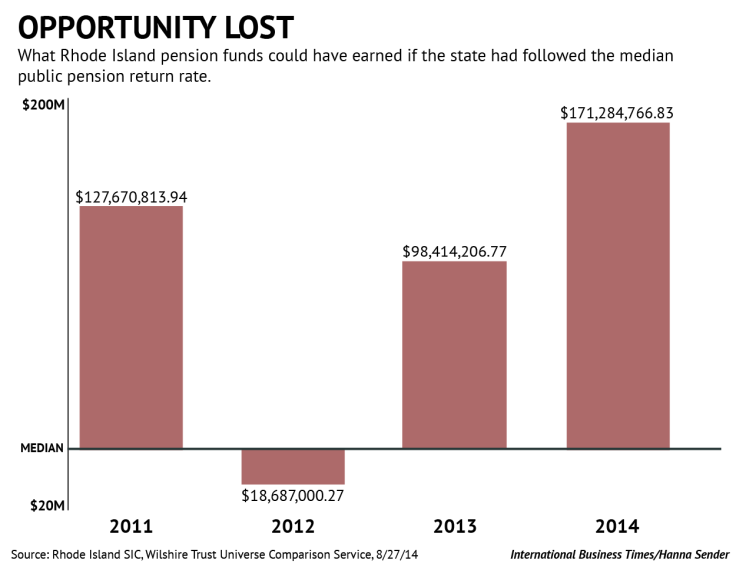

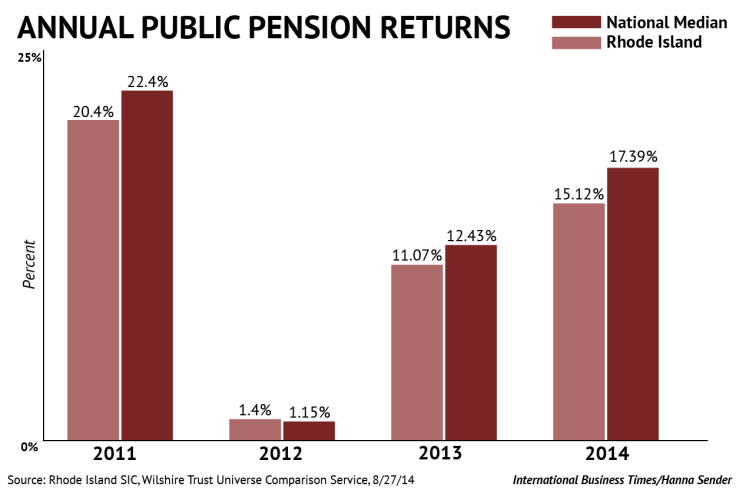

According to four years’ worth of state financial records, Rhode Island’s pension system has delivered an average 12 percent return during Raimondo’s tenure as general treasurer. That rate of return significantly trails the median rate of return for pension systems of similar size across the country, based on data provided to the International Business Times by the Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service. Meanwhile, the pension investment strategy that Raimondo began putting in place in 2011 has delivered big fees to Wall Street firms. The one-two punch of below-median returns and higher fees has cost Rhode Island taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars, according to pension analysts.

Raimondo’s determination to transform Rhode Island’s investment strategy turned “the small state into a national battleground over pensions,” the Wall Street Journal wrote in 2012. Other states such as New Jersey and North Carolina follow similar strategies -- and have also generated below-average returns after plowing pension money into high-fee investments. And in Rhode Island, as in New Jersey and North Carolina, the political leaders pushing to put more money into so-called alternative investments have been backed by campaign contributions from the financial industry. (An NPR affiliate, WFAE has covered this issue in North Carolina.)

The high fees associated with those alternative investments -- costing Rhode Island $70 million in the 2013 fiscal year alone, the Providence Journal reported -- are supposed to buy above-average investment performance. However, according to pension consultant Chris Tobe, the gap between Rhode Island and the median, a gap to which the fees contributed, means the state effectively lost $372 million in unrealized returns.

By way of comparison, $372 million represents more than one-half of the entire annual budget of the state’s largest city, Providence. In all, had Rhode Island’s pension system merely performed at the median for pension systems of similar size, the state would have 5 percent more assets in its $7.5 billion retirement system. Tobe, a former public pension trustee in Kentucky and the author of the book “Kentucky Fried Pensions,” said this difference between Rhode Island and the median can be directly linked to the high fees of the state’s alternative investments, which he said drags the system’s performance below that of traditional public equities.

In response to a request for comment, a representative of the Rhode Island Treasurer’s Office, Ashley O’Shea, said in an email that “it is dangerous to weigh any short period of time too heavily” and she asserted that if Raimondo’s investment strategy had been in place during the 2008 financial crisis, Rhode Island’s “losses would have been mitigated by almost $500 million.” She also said the percentage of the state’s portfolio in alternative investments is at the median, and she argued that giving more Rhode Island pension money to Wall Street firms was a way to reduce risk.

“Rhode Island has a mature plan, that is significantly underfunded, and pays out hundreds of millions of dollars more per year than it takes in, which requires the State Investment Commission to take less risk than younger, better funded plans,” O’Shea wrote, adding that the “strategy is working; the portfolio risk has been reduced substantially and returns remain strong.”

That conclusion was disputed by Edward Siedle, a former U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission attorney who recently published an analysis of Raimondo’s investment strategy for a union representing Rhode Island’s public employees. In an interview with the IBTimes about Rhode Island’s pension system, he said: “Investment fees paid to alternative managers have skyrocketed and benefits to workers slashed to pay Wall Street; performance as compared against the highly liquid, major markets has plummeted; and transparency has been obliterated. For what? Risk reduction? Read the cover of a hedge-fund offering: hedge funds are high-risk, levered, speculative investments. Treasurer Raimondo’s rationale for putting money into alternative assets is like saying sending a gambler to Vegas with pension money reduces risk because his risk does not correlate to the S&P 500.”

Although a small state, Rhode Island has become a major battleground over pension policy and pension politics.

In 2011, national activists such as former Enron trader and hedge-fund manager John Arnold helped bankroll Raimondo’s campaign to reduce pension benefits to state employees, as WPRI noted. Raimondo’s investment strategy earned her an award from the Manhattan Institute -- a conservative think tank whose board consists of Wall Street money managers, some of whom received lucrative pension contracts from Rhode Island during Raimondo’s term, as the Providence Journal pointed out. Raimondo’s bill to reduce pension benefits passed despite the opposition of union groups, which pointed to data showing the moves would hurt the state’s taxpayers and its retirees.

Raimondo is a former finance executive whose old venture-capital firm manages Rhode Island pension money, as WPRI reported. Her close relationship with the financial industry is drawing increased attention in the hotly contested Democratic gubernatorial primary election, scheduled for Sept. 9. Groups backing Raimondo have received $100,000 in donations from hedge-fund manager Arnold, the Providence Journal said. Raimondo herself has raised more than a half million dollars since 2009 from those affiliated with the finance industry. Raimondo has also recently tried to block the release of public records about the pension system’s relationship with Wall Street firms, citing a desire to “to minimize attention around [hedge-fund managers] compensation.”

Raimondo’s opponent, Providence Mayor Angel Taveras, has cited the secrecy, the financial contributions and Raimondo’s high-fee, low-return investment strategy to portray her as a tool of Wall Street. Taveras said that while Raimondo increased Rhode Island state money going to Wall Street investments, Taveras reduced the Providence municipal pension fund’s exposure to those investments.

According to Politifact, Providence now has less of its portfolio in hedge funds than does the Rhode Island government. Additionally, Providence has not only consistently beaten the state’s investment performance but also has beaten the median performance pension systems of similar size over the last four years, according to Wilshire’s data.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.