Ringling Bros. Elephant Lawsuit: Is Legal Vindication For A Circus A Blow For Animal Rights?

HSUS president calls loss a ‘small bump in the road’ in the fight over animal mistreatment.

A 14-year legal circus over alleged elephant mistreatment has ended with animal-rights groups jumping through one final hoop.

For a movement buoyed by significant momentum in recent years, it’s a particularly painful blow: Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, one of its most visible targets, has been vindicated in a protracted legal skirmish with a number of animal-rights groups, including one of the largest in the country, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). Now the groups will have to pay a combined $15.75 million to Feld Entertainment, Ringling’s Florida-based corporate parent, in a settlement reached on Thursday in federal court.

The groups have long objected to the treatment of elephants in Ringling circuses, but in the end they could prove no wrongdoing, and in fact were found to have paid the suit’s key plaintiff, a former elephant trainer for the circus, to the tune of almost $200,000. Is it a minor setback, or does it signify larger failings in a movement sometimes associated with ethically questionable tactics, extremism and sensationalist media campaigns?

In a phone interview Friday, Wayne Pacelle, the longtime president and chief executive of HSUS, was undeterred by the legal defeat. “The wind is at our back on this issue,” he said confidently. “I don’t think this is anything more than a small bump in the road in the public-relations fight over the systemic mistreatment of animals.”

Outside the daily grind of circus tents, SeaWorld protests and Central Park carriage-horse stables, animal rights is a battle of public relations, one that can’t be won without swaying public opinion. Pacelle acknowledged that the animal-rights movement has developed a reputation for extremism, but he denied that this perception has caused harm to a movement that has grown significantly over the years in almost every measurable sense. “No movement is a monolith,” he said. “Whether it’s the women’s movement, the civil-rights movement, the gay-rights movement, you have different tactics, strategies and ideologies ... there is absolutely no question in my mind that the animal-welfare movement is in its ascendency.”

That includes his own group, which he said takes in about $180 million a year in contributions, up from about $75 million a year when he was named president in 2004. He said when he first became involved in animal-welfare activism in the 1980s, there was little awareness of the issue outside of scrappy assemblages on college campuses. “It was a protest movement at that time,” he said. “Now it’s a policymaking movement, with many of its ideas broadly accepted in the culture.”

But policymaking goes both ways, and the brash tactics of animal-rights groups have also been blamed for legislative pushbacks, some of which have had chilling effects on First Amendment rights. Earlier this year, Idaho became the latest of at least seven states to enact a so-called ag-gag law -- legislation that criminalizes undercover investigations at agricultural production facilities. The law was proposed following a 2012 video investigation by the group Mercy for Animals. Masquerading as a dairy farmer, a member of the group captured footage that purported to show local dairy workers beating and shocking cows.

Big Dairy didn’t take the criticism lying down. With the help of lobbying efforts from the agricultural industry, Idaho lawmakers were able to push through the legislation on the grounds that such video exposes are conducted with extreme bias, thereby causing unfair harm to the industry. While journalist groups and free-speech advocates protested the law, some quietly acknowledged that the sensationalist manner in which many animal-rights exposes are presented aren’t helping the movement win broader public support. Leo Morales, communications and advocacy director for the ACLU of Idaho, told IBTimes in February that the pro-ag lobby was quick to capitalize on the questionable reputation of some animal-rights activists. “Groups that opposed this law were called ‘radicals’ and ‘terrorists,’” he said. “These are the terms that the other side has used to really break the credibility of any group that opposes these pieces of legislation.”

Pacelle resisted the idea that PR spin from industries fighting to preserve the status quo pose any sort of long-term threat. “There have been 20 states in 2013 and 2014 that have introduced ag-gag laws, and we’ve defeated every one of them, except in Idaho,” he said.

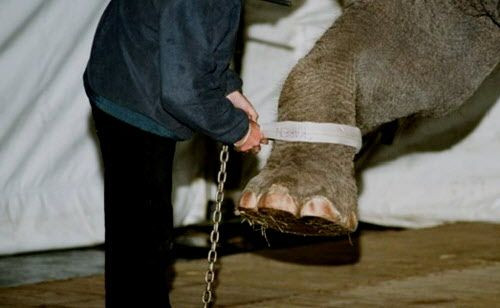

Thursday’s settlement marks the end of a 14-year battle between the self-proclaimed “Greatest Show on Earth” and animal-rights groups that oppose its treatment of Asian elephants, which are used for spectacle in Ringling’s signature traveling circuses. Elephants are among the world's most intelligent species, experiencing a range of complex emotions, self-awareness and even language. In the lawsuit, the groups had claimed that Ringling trainers routinely engage in unlawful activity by beating the animals, hitting them with sharp bull hooks and keeping them chained up for long periods of time.

But in the end, they couldn’t prove it. They also denied that they had paid the case’s key plaintiff, Tom Rider, a former Ringling Bros. elephant trainer. (Rider passed away in 2013.) A spokeswoman for HSUS, which was not part of the original lawsuit, only acknowledged that its affiliate group, Fund for Animals, along with other groups in the case, “had paid some of Rider’s travel expenses [roughly $2,000 dollars, according to one AP report] so he could travel around the country and talk to the media and tell his story of what really happens to elephants behind the big top.”

In its summary opinion, the court found the lawsuit to be “frivolous,” “vexatious” and “groundless and unreasonable from its inception.” Ringling’s response to the settlement was predictable mix of gloating and saber-rattling. “We hope this settlement payment ... will deter individuals and organizations from bringing frivolous litigation like this in the future,” Kenneth Feld, Feld Entertainment’s chief executive, said in a statement. A representative for Feld did not reply to a request for further comment.

Pacelle said he’s not surprised by Feld’s attempt to use the legal victory as an attempt to tarnish the entire animal-rights movement. “He’s a very vindictive guy,” he said. “Ken Feld and his company have a history of retaliatory actions against animal-welfare groups.”

That retaliatory nature, Pacelle said, came in the form of a “baseless” countersuit, in which Feld Entertainment filed a racketeering claim against the animal-rights groups. He said the groups decided to take the $15.75 million settlement rather than suffer the additional court fees of continuing what seemed like an endless legal fight. “It was the right call,” he said.

All of which is to say he believes the animal-rights movement will live to fight another day, and in fact activists are fighting countless fights at any given moment, whether they’re against Ringling Bros., SeaWorld, the dairy industry or puppy mills. These are big targets, Pacelle insists, and to take them on you must be willing to take a few hits. “No progress in any major social movement is linear,” he said. “You get moments when there is a setback.”

Got a news tip? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.