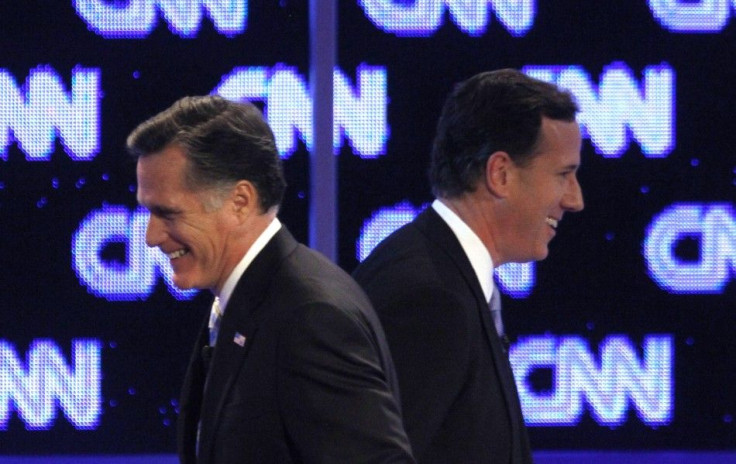

Romney, Santorum Tied in Michigan With 10 Percent of Vote Counted

WASHINGTON (Reuters) -- Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum were virtually tied at about 40 percent each with 10 percent of the vote counted in the Republican presidential primary in Michigan on Tuesday, according to early vote counts broadcast on television networks.

Earlier, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney accused rival Rick Santorum of trying to kidnap Michigan's Republican presidential contest on Tuesday as he faced the possibility of a humiliating defeat in the Rust Belt state where he grew up.

As Michigan voters cast their ballots, opinion polls showed Romney struggling to hold off Santorum in a state he had been expected to win easily a few weeks ago. Members of both parties can vote in the Republican primary, and Santorum has been appealing to the state's Democrats for support.

In an automated robocall, Santorum criticized Romney, a wealthy former private equity executive, for opposing the 2008-2009 government rescue of the Detroit-based U.S. auto industry while backing a Wall Street bailout.

That was a slap in the face of every Michigan worker and we're not going to let Romney get away with it, the call said.

Santorum opposed both the auto bailout and the Wall Street bailout.

Romney said the robocall helps make the race unpredictable.

There's a real effort to kidnap our primary process, and if we want Republicans to nominate the Republican who takes on Barack Obama, I need Republicans to get out and vote and say no to the dirty tricks of a desperate campaign, he told a news conference at his state headquarters in Livonia.

The stakes are particularly high for Romney in Michigan, where he was born and raised and where his father was a popular governor in the 1960s.

A defeat would raise more questions about the one-time front-runner's ability to appeal to conservatives and blue-collar voters in the state-by-state battle to take on Obama in the November 6 general election.

Aides said Romney has the funds and organization to win his party's nomination even if he loses Michigan.

But a Santorum win, on the heels of his victories earlier this month in Colorado, Minnesota and Missouri, could upend the race. Republican Party leaders, concerned that Santorum's religious conservatism could make him unelectable against Obama, may feel pressured to search for a new candidate to join the race.

No matter what the outcome, Romney will likely end the evening with a greater lead over his rivals in securing the 1,144 delegates needed to win the nomination. He is expected to win handily in Arizona's winner-take-all contest, also taking place on Tuesday. Michigan awards its delegates on a proportional basis.

Until recent weeks, Santorum had trailed far behind Romney and several other Republicans vying for the nomination.

But other contenders have faltered, and the former Pennsylvania senator has leaped to the top of the pack, despite a skeletal campaign staff and a fundraising disadvantage.

When asked if he would win on Tuesday during a stop at his Grand Rapids headquarters, Santorum shrugged and quipped: I'm not a pollster. We don't even have a pollster.

In Michigan, Santorum has stressed his own conservative views on social issues and criticized Romney as a moderate.

He is a lightweight on conservative accomplishments, Santorum said at a news conference.

An ABC News/Washington Post poll found Romney at a new low among the most conservative Americans. He is viewed favourably by just 38 percent of that group, the poll showed, down 14 points from a week earlier, while 60 percent view Santorum positively.

'A LITTLE BIT LIBERAL'

I've always liked Santorum but it's more what I don't like about Romney. He is just saying he is a conservative and I do not believe him, said August Vortriede, 53, of Farmington Hills.

Most Michigan polls close at 8 p.m. EST (0100 Wednesday GMT), though some polls in the state's remote Upper Peninsula stay open an hour later.

Santorum's campaign said the robocalls were an effort to reach out to conservative Democrats who supported Republicans like former President Ronald Reagan in earlier elections.

Hopefully we'll appeal to a lot of blue-collar Democrats in this state. I welcome their vote, and I welcome anybody's vote who shares my values, Santorum told reporters.

An exit poll showed Democrats accounting for 10 percent of the vote.

Obama marked Michigan's primary day with a fiery speech to the United Auto Workers union, defending the auto bailout and trumpeting its success. In campaigning, Romney has repeatedly voiced his opposition to organized labour.

I believed in you. I placed my bet on the American worker, Obama said to applause and cheers at the union's convention. Three years later, the American auto industry is back.

Romney is backed by party leaders in Michigan, and his campaign spending here more than doubled Santorum's.

Santorum has the strong support of the state's evangelical Christians, an important Republican voting bloc. In national politics, Santorum is most strongly identified with opposition to gay marriage and abortion rights. He homeschools his seven children and has criticized women who work outside the home.

Romney, whose fortune is estimated at $250 million, has struggled to convince voters that he can relate to average Americans and has made gaffes reminding Americans he is among the super-rich.

Other Republican candidates - Newt Gingrich, a former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and Ron Paul, a Texas congressman - are running far behind the two leaders and have not competed heavily in Michigan, making the state a Romney-or-Santorum contest. (For more on the Republican presidential campaign click on

(Additional reporting by Deborah Charles, Eric Johnson in Michigan, Tim Gaynor in Arizona, and Eric Beech, Susan Heavey and Patricia Zengerle in Washington; Writing by Andy Sullivan; Editing by Doina Chiacu)

© Copyright Thomson Reuters 2024. All rights reserved.