Romney vs. Obama on Auto Bailout: Will Govt.'s $2.43B Loss on GM Stock Matter?

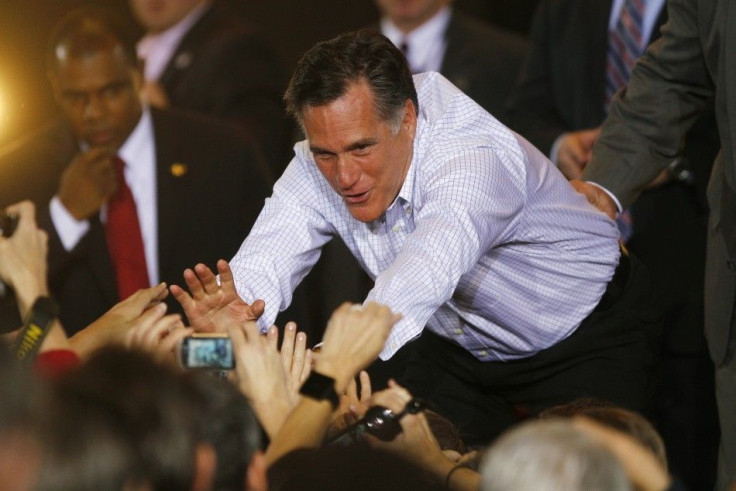

The four words that envelop the headline nag along behind Mitt Romney wherever he campaigns on stops in Michigan.

These were the four words that served as the theme and message of an opinion-editorial Romney penned more than three years ago for The New York Times. It came in the midst of bipartisan bailouts to the swooning auto industry, in a time of debate over how to save what was once Michigan's most prestigious industry in its most prestigious city.

Four years later, the words still trail him as he is battling to squeeze out a victory his home state's Republican primary next Tuesday. Almost unfathomable before fellow Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum's three-state sweep three weeks ago, Romney's downfall in Michigan has become plausible.

Whether his stance on the approximately $80 billion bailouts of General Motors Co. and Chrysler Group LLC enacted by both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama has anything to do with his rapid demise in Michigan is unclear.

With only a week to go before the Michigan Republican primary, one would be hard-pressed to find worse timing for Romney's vitality on the issue. Just last week, GM announced a record 2011 profit of about $7.6 billion, and is looking for profits of $10 billion and up in the coming years. Chrysler announced its first annual net profit since 1997. In 2011, GM once again became the top-selling global auto maker. Analysts regard the auto industry as healthy, partly because of the bolstering and subsequent restructuring provided by the U.S. government loans.

Yet in a poll released Monday by Public Policy Polling, 34 percent of likely Republican voters in Michigan said they would be more likely to support a candidate who opposed the bailouts, as opposed to the 27 percent that said it would be less likely to support that candidate.

That may be, partly, because taxpayers are on track to lose billions on the bailouts because of depreciating stock in GM. The Treasury owns 26 percent of the company's 1.56 billion shares outstanding, or about 405.6 million shares. Those securities have lost $6 since GM's initial public offering in November 2010 for an approximate loss of $2.43 billion.

Meanwhile, Romney's stance has become a target for critics in and out of Michigan. As members of his own party attempt to move the issue to the back burner, Romney has kept it at the forefront. How voters respond in Michigan and upcoming, manufacturing-heavy primary states could provide a glimpse into his fate in a potential general election when pitted against Obama.

The political stakes loom large, and both sides have already begun throwing jabs. And with Republicans campaigning in Michigan, the issue has taken center stage.

GM posted record annual profit today, Obama campaign manager Jim Messina tweeted last week. Glad we didn't let Detroit fail as Romney suggested. Never bet against the American worker!

In the New York Times op-ed, Romney championed his status as the son of an auto executive and his record of restructuring companies during his time with private equity firm Bain Capital. He wrote that if the bailouts were put in place, the U.S. could kiss the automotive industry goodbye.

That was his first problem, said Michael Wissot, a senior political strategist at the Republican group Luntz Global. He took a hardline stance on an issue and now finds it difficult to retreat.

If that candidate says that a bailout will succeed or fail in keeping an industry afloat, as happened in the case of Gov. Romney, then they're beholden to the actual result, Wissot said. That's a problem. Candidates should make commitments and defend principles. Making promises, guarantees and even predictions is simply playing Russian Roulette.

But Romney has continued to play, penning another op-ed last week in The Detroit News that repeated his attacks on the auto industry bailout. The piece prompted a slew of criticism by everyone from the United Auto Workers union to Steven Rattner, the former head of Obama's auto task force, which cut the deals for the government loans.

Romney wrote in the op-ed that, in effect, the UAW was rewarded for campaign contributions to Obama in 2008, something UAW President Bob King responded to by saying that Romney turned his back on the industry when it was in its darkest hour.

The greater hit is on Romney because he's been so vocal for so long, said Peter Fenn, a Democratic political strategist whose Fenn Communications Group has worked with GM in the past. My sense is that doubling down on his initial mistake is not the wisest political move.

Meanwhile, Obama has also thrown out strong rhetoric against a proverbial Republican challenger, though he benefits from signing off on a plan that has coincided with renewed growth and health in the auto industry. He swipes at some who thought the industry should die.

The Democratic National Committee spews out number after number it claims wouldn't have been possible without the president's decision -- nine million vehicles sold, $7.6 billion in profits (for GM), 1.4 million American jobs saved in the industry, more than 200,000 jobs added since restructuring.

The challenge for Romney or any potential Republican candidate comes against these numbers in a general election. The PPP poll only measured likely Republican voters, and another PPP poll last week showed Obama leading Romney by 16 points in a theoretical November matchup, up from only four to seven points in 2011 polling. And after the Michigan primary comes challenges in the automotive industry and manufacturing-heavy states of Alabama, Illinois, Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee.

Combating the numbers begins with changing the rhetoric, Wissot said. He said Romney has become almost defensive over his stance. For example, something that could sway voters is GM's depreciating stock and the government's likely loss in that stock.

A government spokesman said by phone last week that he wouldn't comment on the speculative future of when the government might look into selling its approximately 26 percent stake in GM, but he said he did not know of plans to do so.

That's something Romney could point to as an example of philosophy -- why government should not get involved in the private sector.

I think that's something to keep an eye on, Fenn said. I wouldn't count anything out right now. I'm not sure this is a completely done deal.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.