Scientists Discover Hypervelocity Star, Ejected By Supernova, Hurtling Through Milky Way

US 708, first discovered in 2005, was once a normal red giant star in a binary star system. That is, until it was stripped of all its hydrogen and some of its helium by a perpetually hungry orbiting partner, which then detonated in a massive supernova -- an explosion that was so tremendous that it catapulted the ravaged remains of US 708 with a velocity greater than that of any other star in the galaxy.

US 708, now transformed into a hypervelocity star hurtling through the Milky Way at about 745 miles per second (2.7 million miles per hour), is traveling fast enough to escape the gravitational pull of the galaxy, according to a recent study published in the journal Science.

“At that speed you could travel from Earth to the moon in five minutes,” Eugene Magnier from the University of Hawaii, and a co-author of the paper, reportedly said. US 708 will leave the Milky Way in about 25 million years, eventually making its way to intergalactic space and cooling down to form a white dwarf star.

However, the star’s velocity is only one thing that makes this discovery an exceptional one.

US 708 is not the first star discovered by astronomers found to be moving fast enough to escape the galaxy’s gravitational pull, but it is the only one so far that appears to have been slingshot as a result of a supernova explosion. Other such hypervelocity stars are believed to have been flung out into space by the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

“US 708 does not come from the galactic center. We don't know any other supermassive black hole in our galaxy. One needs one of those. A smaller, stellar-mass black hole formed by the collapse of a massive star can't do the job,” Stephan Geier from the European Southern Observatory, who was involved in the study, told Discovery News.

More importantly, the discovery could shed light on how this type of supernova, known as Type Ia, occurs.

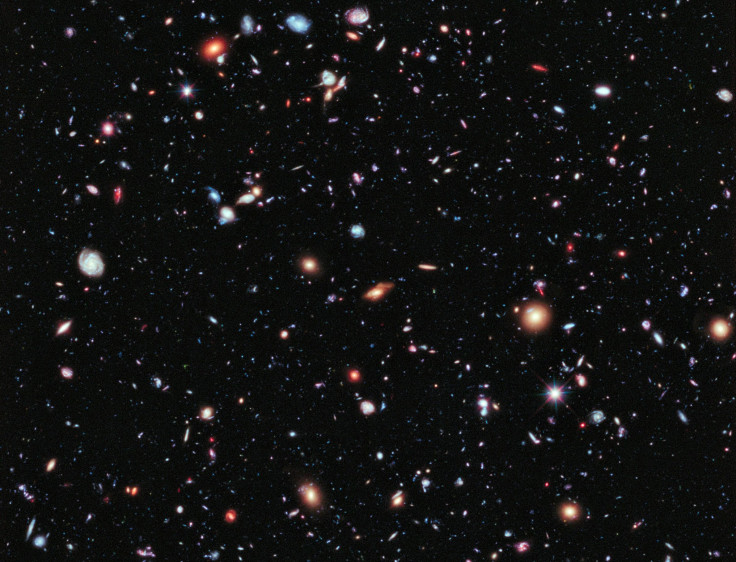

“We have made an important step forward in understanding (type I supernova) explosions,” the researchers reportedly said. “Despite the fact that those bright events are used as standard candles to measure the expansion (and acceleration) of the universe, their progenitors are still unknown.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.