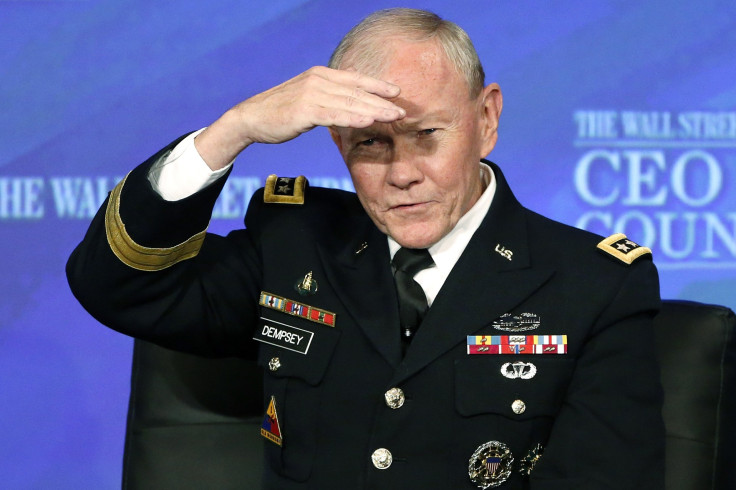

Senior Military Official, Martin Dempsey, Discusses Domestic Military, Middle East Options And Asia Fears

Top U.S. military leader and chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, gave a wide-ranging interview on Monday night at an annual summit of international business executives in Washington, where he touched upon Syrian intervention and Japanese military reforms, among other topics.

Here are some key takeaways from the interview with John Bussey, the Wall Street Journal's executive business editor.

Domestic Military Questions

Asked about his priorities for the U.S. military, Dempsey focused on completing already set national objectives, like ending conflict in Afghanistan, and keeping tighter links with veterans and the broader American military family.

In the context of tight budgets, sequestration, and potential changes to military pay, Dempsey added that he preferred long-term budget planning. He meant that the military should mold, and not “back into” or react to, budgets running up until fiscal year 2020.

“It’s also about making sure they’re well-trained, well-led, and well-equipped,” Dempsey said, speaking of U.S. military personnel. “If I don’t get the manpower costs under control, then the institution will suffer irreparable harm in modernization, training, and readiness.”

He estimated over the weekend that manpower costs could eat up to 60 percent of the defense budget, up from half, if there weren’t compensation reforms. The U.S. Department of Defense requested $526 billion in funding for fiscal year 2014.

The Middle East

Speaking of the so-called Arab Spring protests, Dempsey said: “You have a changed relationship between the governed and the governing, among a populace that doesn’t know what to do with it, frankly.”

“It’s a bit naive to think that in the first generation of that change we would move somehow from dictatorship to democracy, certainly,” he continued.

Dempsey said recent transfers of power were only first steps in a story that could take a decade or more to settle, and involved societies freeing themselves from suppression by dictators. The Arab spring was “hijacked” by extremists on both sides of the Sunni-Shia divide, continued Dempsey.

He underlined that the U.S. still has a “deep obligation” to Israel, to whom the Obama administration requested $3 billion in foreign military aid in fiscal 2014, according to the Congressional Research Service. That’s part of a 10-year $30 billion military aid package spanning fiscal years 2009 to 2018.

If Israel were to bomb Iran, in this period of heightened tensions, the U.S. would have “defined obligations” that it’d meet, Dempsey said, without elaborating on the details.

On U.S. military intervention in Syria, Dempsey had this to say: “My obligation is to articulate options and articulate risk, and those we elect make decisions about which options they’re interested in.”

“Are the options [in Syria] getting better? No, I don’t think so. I think they’re probably becoming more complex.”

He referenced earlier intervention options, suggested in a July letter he sent to Sen. Carl Levin, D-Mich., like a no-fly zone or the seizure of chemical weapons, but added: “History’s against those who think they can limit conflict.”

Concerns In Asia

Dempsey also ducked a question about Japan’s moves to amend its constitution to revive its military prowess, and whether he’d endorse that strategy to counter China’s power in the region, for instance.

Whether a resurgent military Japan would be a valuable development is a question “to be determined,” he said. “For some time, we have encouraged Japan to match its economic power…with some extended military capability,” adding: “Not to threaten any particular player in that part of the world, but rather to make us a more capable alliance.”

Recent territorial disputes in the region, chiefly between China and Japan, could be managed diplomatically, in Dempsey’s view. And, he seemed unafraid of Chinese military muscle, saying: “I worry more about a China that falters economically than I do about them building another aircraft carrier, to tell you the truth.”

On that, he is in agreement with many economists, who have predicted that slowing economic growth in China could hugely impact the global economy.

“I think we can find a way forward with them militarily. It’ll be competitive, and at times it will be contentious, but it doesn’t have to be confrontational,” he continued, of U.S.-China military relations.

The real threat, according to Dempsey, comes from North Korea. “I actually worry more about a provocation from Korea that escalates, than probably anything else I deal with on a daily basis,” he said.

Deliberate provocations from the country can be tough to contain, and China can’t always do it alone, he said.

“We have these cycles of provocation, we happen to be in a cycle where the provocations are absent right now,” he remarked. “But we’ll see.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.