Super Bowl 2014: Bonuses, Trademark Rights And Brand Value: What’s Really At Stake For The Players And The NFL?

This is the first in a five-part IBTimes series examining the economic impact of the Super Bowl.

The Super Bowl is nothing if not a game of superlatives. It’s often the most-watched television broadcast in any given year. It generates more tweets and it commands higher ad revenue than any other sporting event in the world. Calculating the average revenue from sponsorships, tickets and licensed merchandise, Forbes magazine in 2012 estimated the Super Bowl brand to be worth $470 million; no other game comes close.

And when the Seattle Seahawks face off against the Denver Broncos for Super Bowl XLVIII this Sunday at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J., hundreds of millions of dollars will be exchanging hands in ticket sales, TV commercials, gambling, hotel bookings, travel costs, alcohol and snack foods. But lost in the commercial hoopla surrounding this national quasi-holiday is a surprising outcome: Very little of this money will find its way to many of the people who make football happen -- the players, the teams and the National Football League itself.

What The Players Get

Most of us have seen Peyton and Eli Manning rapping their way through those campy, 1980s-inspired DirecTV commercials. But few NFL players hail from a prominent football dynasty or have the individual star power to command that kind of payday. Indeed, for every Super Bowl alumnus who is showered with endorsements, hundreds of virtual unknowns face premature ends to their careers due to an injury or poor performance.

Industrywide, there is some disagreement over the shelf-life of a typical NFL player. The NFL Players Association, the labor union that represents the players, estimates that the average career lasts only 3.5 years. But the NFL itself has challenged that figure, saying the association deflates the average by factoring in players who never make a team’s 40-man squad. “If a player makes an opening-day roster, his career is very close to six years,” Roger Goodell, the NFL’s commissioner, insisted in a 2011 statement. “If you are a first-round draft choice, the average career is close to nine years.”

But no matter how you measure it, life on the football field is a relatively short one -- most players peak before age 30 -- and it’s not always as lucrative as popular opinion suggests. In 2012, the minimum salary for rookie players was $390,000 a year. It’s a comfortable living, for sure, but not exactly a gold mine for players whose careers will be over before very long.

And things can get decidedly bleaker in retirement. One study by the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research found that, for younger NFL retirees, the proportion of men with income below the poverty level is not much different from that of the general population. One reason is that the majority of ex-players can’t expect to fall back on income related to their football careers. The 2009 survey, which looked at 6,983 NFL retirees, revealed that only about 14 percent of younger NFL retirees, and 5 percent of older ones received any type of endorsement money. Another is health care costs associated with the myriad of health problems ex-NFL football players are now known to suffer from. The numerous collisions and injuries can lead to anything from joint replacements to neurodegenerative disease, and the NFL’s insurance program doesn’t always cover the bill, as the Washington Post reported last year.

Given such precarious variables, it’s easy to see why football players would welcome the bonus money they get from playing in the Super Bowl, even if it is small change in the bigger scheme that this game represents. The bonuses for playing in the Super Bowl tend to go up every year, negotiated by the NFL Players Association. This year, players on the winning team will receive a $92,000 bonus, a 6 percent increase over last year. Players on the losing team will receive $49,000. Individual players may also have additional Super Bowl bonuses written into their contracts.

But it’s not just the Super Bowl itself that nets extra cash. Each step of the post-season playoffs comes with bonuses for both the winning and losing teams that could double the amount of money a Super Bowl-winning player receives. Considering that the playoffs last only four games at most, salary-wise “it’s like having another season,” said Carl Francis, director of communications for the NFL Players Association.

Less certain is the value of participating in the Super Bowl to players throughout their careers and into retirement. Some Super Bowl veterans become household names purely because of their exploits during the game. Before 2010, quarterback Drew Brees had only done a handful of promotional work for groups like the United Way and Cox Communications. But after he led the underdog New Orleans Saints to victory over the Indianapolis Colts in Super Bowl XLIV, the offers started pouring in. These days, Brees makes a reported $11 million a year in endorsements for companies including Nike, Verizon Wireless, PepsiCo and numerous others.

But most of the other players, particularly in the so-called nonskilled positions like offensive linemen and defensive backs, enjoy no bump at all from a Super Bowl ring. “It’s a diverse group,” said David Weir, a research professor and one of the authors of the University of Michigan study. “Popular observation suggests that while some get rich by ‘going to Disneyland,’ some of them may lose money on all the partying.”

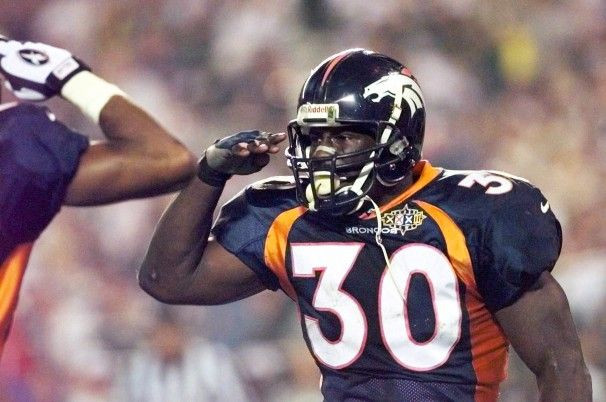

At least two former Super Bowl star alumni -- Dexter Manley of the Washington Redskins and Joe Gilliam of the Pittsburgh Steelers -- are said to have pawned their Super Bowl rings for drug money. (Manley got his back after his lawyer retrieved it, the Washington Post reported.) And in many cases, a promising post-Super Bowl career is simply cut short by an injury. Terrell Davis, for instance, led the Denver Broncos to back-to-back Super Bowl victories in 1997 and 1998. The following year, he tore ligaments in his right knee and was all but sidelined until he finally retired in 2002 at the age of 29. Most casual fans, and even some noncasual ones, would have a hard time remembering who Davis is today.

What The Teams Get

Unlike the players, NFL teams that make it into the Super Bowl reap their monetary reward largely through an increase in brand value. (It’s hard to imagine the owner of the Seattle Seahawks, billionaire Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, waiting around for a five-figure bonus.) There are 32 teams in pro football, and only one per year gets to call itself the Super Bowl champion. That title can make a difference in terms of what the team is worth, at least according to valuations from Forbes magazine, which has been ranking the teams’ values for the last seven years.

In 2010, for instance, the Pittsburgh Steelers were ranked No. 17, with a value of $996 million. The Green Bay Packers were ranked No. 14, with a value of $1.02 billion. The following February, the Packers and the Steelers faced off in Super Bowl XLV. In Forbes’ 2011 rankings, the Steelers edged up three slots to No. 13, and their value increased 2 percent to $1.02 billion. For the Packers, the winning team, the jump was even more dramatic. The team edged up five slots to No. 9, with a 7 percent increase in value to $1.09 billion.

A Super Bowl win, however, appears to make less of a dent in the values of larger franchises. In 2013, the New York Giants stayed at No. 4, where they consistently rank, despite a Super Bowl win the previous February.

What The NFL Gets

The official mission statement of the National Football League is to “promote the interests of its 32 member clubs,” but you won’t hear about how much profit the organization takes in from the Super Bowl. That’s because that number is zero, at least on paper. The NFL, while it oversees a more than $9.5 billion-a-year industry, is not a for-profit venture. It’s is a registered 501(c)(6) organization, a nonprofit status reserved for business leagues, chambers of commerce and the like. NFL teams make a profit; the NFL itself technically doesn’t.

In the tax world, that’s a coveted designation, one that has earned the organization its share of critics, many of whom accuse the NFL of getting a free ride on the backs of taxpayers. Major League Baseball gave up its tax-exempt status in 2007, and the National Basketball Association never enjoyed nonprofit status.

Though the NFL is a nonprofit, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t generate revenue. According to its form 990 from 2011, the most current year available, the NFL brought in $255.3 million. The vast majority of that money -- $254.6 million -- came from membership dues paid by the teams. The organization took in another $584,500 in fines and another $183,157 income from tax-exempt bond proceeds.

But the NFL’s expenses that year were $333 million, meaning it was $77.6 million in the hole when all was said and done. Salaries made up nearly a third of those expenses, with no less than six NFL employees making $1 million or more. Roger Goodell, the league’s commissioner, had reportable compensation of $29.4 million in 2011. Jeff Pash, the NFL’s executive vice president and general counsel, took home $7.2 million. In all, the NFL spent $107.8 million on salaries, benefits and other compensation.

The NFL is vigilant -- some would say too vigilant -- in protecting what is perhaps its most valuable Super Bowl-related asset: the trademark to the term “Super Bowl” itself. The organization is notorious for its heavy-handed saber rattling, firing off cease-and-desist letters to unauthorized companies that make direct references to the event in their promotions. (“The Big Game” has emerged as the accepted code word.) Ron Coleman, a partner and commercial litigator at Goetz Fitzpatrick LLP in New York, said any relatively high-profile operation -- a bar in Midtown Manhattan throwing a Super Bowl party, for instance -- has to be careful not to refer to the Super Bowl by name.

“Even businesses that could never in a million years afford to buy a license will get a cease-and-desist letter,” Coleman said in a phone interview. “And the NFL doesn’t bluff. They need everyone who is in their zone of influence to be aware that they’re not kidding, that they do enforce the trademark.”

Coleman has been a vocal critic of the NFL’s trademark-enforcement policy, calling out the organization for bully tactics and claims of quasi-exclusivity, which he said are “not legally meritorious.” “Everyone in the world knows that if Jim’s Bar has a Super Bowl party, it’s not an NFL-approved event. There’s no chance whatsoever of confusion of sponsorship or affiliation.”

At the same time, Coleman acknowledged that, from a financial standpoint, it simply wouldn’t be worth it for Jim’s Bar to escalate the issue. Hence, the NFL, which paid $10.3 million in legal expenses in 2011, never has to test its trademark tactic in court, since businesses on the receiving end of one of its letters almost always back down first. “It’s just a perfect example of the guy with the money wins,” said Coleman.

Despite criticizing the NFL’s tactic, Coleman called it “commercially brilliant.” That the NFL is known to aggressively defend its Super Bowl trademark generates word of mouth about exclusivity, thereby raising the stakes for sponsors willing to pay the hefty licensing fees for the use of the trademark. The fees, which are not shared publicly, are licensed through the privately owned NFL Properties LLC, which also manages the trademarks for Pro Bowl, the NFL shield and the team names and nicknames. Coleman clarified that the NFL’s strategy is a relatively common one among owners of well-known trademarks, and in the end “it’s not a crime against humanity.”

“They’re most interested in revenue opportunities,” he said. “They want those programs that do license the word ‘Super Bowl,’ knowing that they’re getting something super-duper exclusive. If you’re Pepsi, you’re paying a big premium because not everyone gets to call anything Super Bowl.”

Whatever you choose to call it, this Sunday’s big game is expected to attract an audience of more than 100 million people. For the 40 or so players who are lucky enough to be in the middle of the action, it will be more than a spectacle; it will be a lifetime high, regardless of what the future holds.

Which brings us back to Terrell Davis. Earlier this month, the retired Denver Bronco was passed over by the Pro Football Hall of Fame for the seventh year in a row. In the eyes of the Hall’s voters, Davis’ short career just didn’t have the longevity necessary to warrant inclusion. Now 41, Davis may very well believe his best years are behind him, despite the occasional appearance on Sesame Street. But no matter what, he’ll always have those two rings. Asked whether most NFL retirees consider a trip to the Super Bowl worth the lifetime of uncertainties, Carl Francis at the NFL Players Association found it difficult not to use a superlative. “For every player who plays the game, it’s the ultimate,” he said.

Got a news tip? Email me. Follow me on Twitter @christopherzara.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.