Too fragile, too frosty...

The peace between Israel and Egypt

Finally, the last of the unforeseen events has struck. The bewildered world watched an Arab leader at the Ben Gurion airport, smiling and waving to a cheering crowd. Gun shots, 21 of them, were fired in his honor and the man with a countenance was seen paying his respects to the Israeli national anthem.

It was seen as the biggest political gamble of our times, and as an audacious move from a leader battered by war and domestic issues.

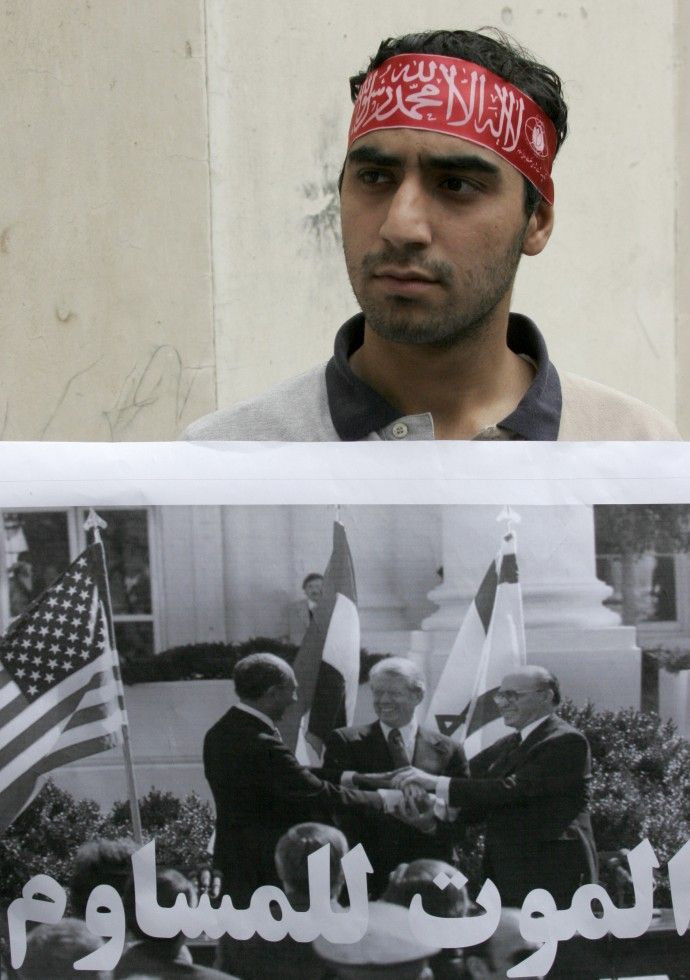

Flouting an age-old Arab practice on this day (19 Nov), 33 years ago, Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat met with Israel's Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Adding pages to the history pages, this event became the first ever visit to the Jewish state by an Arab leader.

In his address the Knesset (Israeli parliament) he reached out to millions of people across the world with a modest message.

I come to you today on solid ground to shape a new life and to establish peace.

An uneasy peace prevailed between the two countries ever since. But given the current times, analysts say that the toughening of the 'right' in Israel and the shifting political scene in Egypt could throw things off balance.

Egypt, the biggest ally of the United States in the Arab world had enjoyed a $2-billion aid every year since Sadat signed a peace treaty (Camp David Peace Accords) with Israel in 1979. After Sadat, Hosni Mubarak, currently 83, took control of the state for 29 years and maintained a status quo in the affiliation. But, the nation of 83 million is set for polls this month and experts predict a definite replacement of Mubarak.

As a decorated military officer, he strengthened the security forces and silenced all opposition. But, now the Egyptian president appears frail after he underwent gall-bladder surgery in March this year. Some media reports have already suggested that he could run for his sixth six-year term and can score a win too. But with unemployment peaking at 25 per cent and an upward inflation, Egyptians are likely to look for alternatives.

Mubarak's two sons, Alaa and Gamal, may not fit the bill though for their reputation already tarnished by allegations of corruption. Omar Suleiman, the chief of intelligence and Mohamed El Baradei, the retired chief of the International Atomic Energy Agency, are favored to run for the polls but yet there are complaints that none could turn out to be a charismatic leader.

Nevertheless, the biggest worry to Mubarak is the ever-rising opposition of the Muslim Brotherhood. In the 2005 election, the proscribed party got its strongest political foothold ever, securing 34 seats and almost doubling its presence in parliament. Regardless of restrictions, the party this time, is fielding candidates for 134 out of the 508 elected seats in parliament, all of them as independents.

Despite government cracking down on Brotherhood, observers suggest that the group is likely to rebound and secure a considerable share in the government. The Brotherhood's ideologue, however, considers Israel an occupier, and occupation needs to be resisted by all means. Like several other Islamist organizations, it too has a hostile policy against the West and the United States. The growing influence of the party in Egyptian politics is seen as a peril to Egypt's relations with the Jewish state and its western allies.

Egypt would regress 100 years if the Brotherhood came to power, General Fouad Allam, a former chief of Egypt's internal security services told the Time magazine recently. He maintained that the Islamist takeover would change Egypt's current peace treaty with Israel completely.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the border, the hard 'right' is moving swiftly towards taking control. Leaders of settler groups have vowed to end Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu's terms as Prime Minister if he accepts the U.S. proposed renewed moratorium on construction activity in West Bank and East Jerusalem. They have found a face to represent them in Avigdor Lieberman, the leader of Israel Beiteinu. Or popularly known as the man who said Hosni Mubarak Can go to hell in 2008.

Lieberman, Israel's ultranationalist foreign minister heads the party that captured 15 seats in the last elections. But, he remains popular among immigrants from the former Soviet Union and other right-wing activists. Distrustful of the peace process with the Palestinians, the minister also believes that Israel should be working on long-term solutions rather than rushing to reach an agreement.

We will not accept any additional freeze - not for three months, not for a month, and not for a day, he told the Jerusalem Post last week.

Prominent Rabbis like Elyakim Levanon, who heads of the Elon Moreh Yeshiva, has been lately warning Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, that the national-religious sector would call on their followers to support Lieberman as the next head of the state.

Unlike Netanyahu, he will continue to speak the truth as the head of the state, the Haaretz quoted Levanon as saying about Lieberman.

Not heeding to condemnation, Netanyahu meanwhile, seems confident to push for the renewed moratorium in the parliament over the next few days.

But, he will have to certainly fight the cabinet which has been fiercely opposing any restrictions on Jewish housing activity. A major error can throw his political career off-balance and simultaneously strain the diplomatic bind with its neighbor.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.