Welcome To The Million-Dollar Podcast: A Niche Medium Grows Up A Bit And Advertisers Start To Notice

Apple Inc.’s iTunes Store reached a landmark 1 billion podcast subscriptions last summer, and with that announcement covered by the likes of Macworld came the expected deluge of “Podcasts Are Back” trend pieces, as exemplified by USA Today. The digital audio medium that exploded during the iPod revolution fell on dubious times in the mid-2000s, but the proliferation of mobile devices spurred a renaissance of sorts in this decade, with countless high-profile personalities -- Adam Carolla, Marc Maron, June Diane Raphael and Joe Rogan among them -- elevating the craft to an even higher profile.

So we know podcasts are back, or maybe they never went away: But are they profitable? Monetizing this burgeoning format is the next great challenge for the audio industry, and those on the front lines say they are meeting it head-on.

“Sponsors and advertisers are definitely paying attention -- and stepping forward,” said Jake Shapiro, CEO of Public Radio Exchange, or PRX, which produces the podcast collective Radiotopia. “We get in-bound inquiries now, ringing us up saying, ‘We want in, so how do we do it?’”

Shapiro is a veteran of public radio and said many podcasts employ a similar business model, using a combination of sponsorship, advertising and various types of fundraiser appeals. For instance, Radiotopia is currently in the thick of a Kickstarter campaign that has raised more than $396,000. It was asking for only $250,000.

If nothing else, the campaign’s runaway success should be enough to convince major brands that consumers are listening, but Shapiro said the flow of ad dollars is still catching up to changes in audio-consumption habits.

“It’s still emergent,” he said. “Brands and companies that want to sponsor podcasts are still wrapping their heads around what it really means. The metrics aren’t fully in place, but the level of listening and engagement -- and the opportunity to get into the very intimate medium of spoken-word audio in someone’s headphones -- is just a really powerful place to be for brands. So it’s starting to command a premium.”

Money Talks

Enter Midroll Media LLC, a media-buying firm that specializes in selling ads specifically for podcasts. Since its launch two years ago, its quarterly revenue has doubled year-over-year almost every quarter, according to Erik Diehn, the company’s vice president of business development. “Our revenue growth has been dramatic,” he said.

Midroll is essentially filling a niche that many in the radio industry didn’t know needed to be filled. The company now sells advertising for about 130 podcasts, including podcasts for Slate Media and popular titles such as “WTF with Marc Maron.” Midroll doesn’t share revenue figures, but Diehn said he expects four of its most widely heard podcasts to gross more than $1 million in ad revenue in the next year.

Diehn credits Midroll’s growth to younger brands -- many tech startups -- that have been quicker to recognize the value of podcasts than have older brands and that also have an interest in direct-response-type advertising. Podcast ad units are measured in cost-per-thousand impressions, or CPMs, as opposed to through traditional ratings such as those of the Nielsen Co. Brands such as LegalZoom, MailChimp and Squarespace, which may not have the ad budgets to book expensive broadcast-radio spots, are common fixtures on podcasts.

Conversely, more-established brands such as those of the Coca-Cola Co. and McDonald’s Corp. are still bogged down by what Diehn calls the “structural baggage” of marketing departments too focused on the old way of doing things. “They have buyers who are used to buying gross ratings points,” he said.

Of course, it’s only a matter of time before mainstream brands catch on, but Diehn said they might consider leaving some of their more annoying advertising habits behind. He said intrusive radiolike commercials won’t fly with discerning podcast audiences, who want a more purposeful listening experience than does the typical passive AM/FM dial-surfer. He said Midroll has had the most success with unobtrusive ad spots read directly by the on-air talent -- hosts who have built-in listener trust.

“The recall rates are much better than you would get with, say, some sort of injected, precanned creative spot stuck in the middle of six tracks on a Pandora stream,” Diehn said. “If you’re listening to classic rock [songs], and all of a sudden there’s this screaming ad for a car dealer, the intrusion factor is off the charts.”

Decade Of Disruption

The modern idea of the podcast can be traced back to a 2003 demonstration at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Only a few years later, however, commentators were writing obituaries for the social-media form. Clunky interfaces, slow connections and a multistep downloading process frustrated would-be listeners. For a while, it looked like the podcast might be little more than a passing fad, durable enough to hold on to a tech-savvy niche audience, but no real threat to traditional radio broadcasters.

Then the iPhone happened, and suddenly anybody could load a podcast with just a few taps of his or her screen. As smartphone penetration grew in the late ’00s and early ’10s, the popularity of podcasts grew with it. “The smartphone is a terrific audio vehicle,” said Thomas Hjelm, chief digital officer for New York Public Radio, home of WNYC. “It’s the transistor radio of today.”

The shift to on-demand radio audiences mirrors the transition experienced by television, whose conventional model has been upended by digital video recorders and streaming services such as the one offered by the market-leading Netflix Inc. Hjelm said New York Public Radio has seen significant growth in on-demand listening, but he said the “bullhorn” of broadcast is still a key way to promote a show’s awareness. The two formats are more symbiotic than are competitors, he said.

Indeed, the most popular podcasts are still broadcast properties, and many existed on radio before the iPod revolution. “This American Life,” WNYC’s “Radiolab,” and NPR’s “Fresh Air” typically rank in the top 10 on the iTunes charts. Others such as “Freakonomics Radio” (No. 3 on the charts this week) have built-in brand recognition. But more radio producers are experimenting with digital-first properties. “Serial,” the new “This American Life” spinoff hosted by Sarah Koenig, is already a bona fide cult hit.

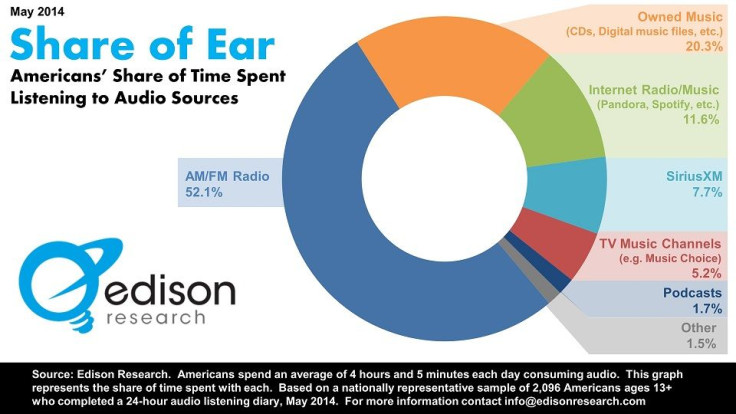

According to a recent study by Edison Research, podcasts account for only 1.7 percent of our total audio-consumption time. AM/FM radio is still responsible for more than one-half. But Diehn said those who become avid podcast users tend not to go back to broadcast radio. Traditional radio may have a synergistic relationship with podcasts at present, but Diehn believes a shift is coming, and in the end America only has so many eardrums to go around.

“In that respect, I think we are competing,” Diehn said. “And not just competing, but I think we are largely going to win in the long run.”

Got a news tip? Email Christopher Zara here. Follow him on Twitter @christopherzara.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said four of Midroll’s podcasts have already grossed over $1 million. They are expected to gross $1 million in the next year.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.