Why Erdoğan’s Visit To The US Is Drawing Controversy: Everything You Need To Know About US-Turkey Rift

When President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan last visited the U.S., he was received warmly by President Barack Obama, who praised his recently launched peace initiative with Kurdish militants. But as he touched down in Washington, D.C., this week, nearly three years later, Erdoğan got the apparent cold shoulder from the White House. Obama turned down a formal, one-on-one meeting with the Turkish leader, a key NATO ally, despite reports in Turkey that one was scheduled.

Although Turkey remains an important strategic ally in the Middle East for the United States, a growing rift has coincided with the heavy scrutiny of Erdoğan’s targeting U.S.-allied Kurdish militants in Syria and overseeing an alleged brutal crackdown on dissent at home. With a lengthy list of human rights violations, Erdoğan, who was in the U.S. for a nuclear summit, was instead scheduled to meet Vice President Joe Biden. The Turkish leader was also set to attend the grand opening of an Ottoman-style mosque in Maryland, the Diyanet Center of America, which was funded by his government.

U.S. officials rebuffed allegations that Obama’s decision to forego a meeting with his Turkish counterpart was meant as a snub, noting that delegations from 51 nations were expected to attend the summit. Only Chinese President Xi Jinping has a meeting scheduled with Obama. Whether or not the decision for Obama and to not meet with Erdoğan was related to the rift between Turkey and the U.S., it was undeniably read as such in both the U.S. and the Turkish press. However, it's likely the two leaders will meet in some capacity on the sidelines of the Nuclear Security Summit.

Erdoğan was elected prime minister in 2003, vowing to usher in a fresh era of democracy in a country that had been plagued by shadowy military influence for decades. By many accounts, he overturned a system that was repressively secular, as he pushed for women to have the right to wear Islamic headscarves, which they had been forbidden to do in public institutions, despite the country's Muslim majority. He also oversaw an era of exceptional economic growth, pushing Turkey from an aid recipient to a major global donor, and was held up as proof a Muslim head of state could also be a democratic leader.

But these days, Turkey has been rattled by routine bombings, its economic growth has slowed and media and opposition parties have come under sharp government pressure. Erdoğan himself has switched titles from prime minister to president after exhausting his term limits and now hopes to rebuild the country on a presidential system — a proposal critics say reflects his authoritarian tendencies. Whether the U.S.'s reliance on Turkey in the fight against ISIS will keep ties strong is the question that now looms.

Here are some of the major issues that have strained U.S.-Turkey relations:

Fighting Kurdish Rebels in Syria. At the heart of the disagreements between Washington and Ankara lies policy toward Syria. The U.S. and Turkey appear to be in agreement that Syrian leader Bashar Assad and ISIS both have to go. The U.S. military operates out of Turkey's southern Incirlik Air Base, and Turkey is part of the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition. Yet, whereas the U.S. views Kurdish rebels with the Democratic Union Party (PYD) as crucial allies in the fight against ISIS, Turkey has fought its armed wing, the Kurdish People's Protection Units.

"Until either or both of the sides revise their approach to PYD, the US-Turkey relationship will continue to be poisoned by this issue," Ozgur Unluhisarcikli, Ankara Office Director of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, told Agence France-Presse.

Turkey views the Kurdish group as a wing of the Kurdistan Workers' Party, better known as the PKK, which has for decades been fighting a guerilla war against the Turkish government. Both the U.S. and the EU have labeled the PKK a terrorist organization, but the label is not applied to the PYD. Turkey fears that if the PYD is successful in building an autonomous Kurdish region in northern Syria, along the Turkish border, it will embolden Kurds in Turkey to join the fight for self-rule.

Needless to say, the U.S. is in a tricky position: funding one ally (Kurds) who are being shelled by another (Turkey).

A War Against Kurds at Home. With the recent spillover from Syria, a tenuous ceasefire between the PKK and Turkey collapsed last summer. The fresh wave of violence unleashed terror attacks across Turkey and turned Turkey's restive, predominantly Kurdish, southeastern region into a war zone. The Turkish government placed several cities under curfew and intensified its rhetoric against pro-Kurdish political parties. Kurdish militants have responded with increased violence as calls for self-rule have amplified.

Turkey claims to have killed more than 5,000 Kurdish militants in the fighting, which also expanded into Iraq, where some of the PKK militants are based. More than 350 Turkish security forces were killed in the fighting. But civilians bore the brunt of the violence as more than 500 noncombatants were reportedly killed. The U.S. has not taken a strong stance on the spiraling conflict in Turkey's southeast, but human rights groups have repeatedly lambasted the Middle Eastern ally.

“The Turkish government should rein in its security forces, immediately stop the abusive and disproportionate use of force and investigate the deaths and injuries caused by its operations,” Emma Sinclair-Webb, senior Turkey researcher at Human Rights Watch, said.

Cracking Down on Dissent. Despite it once seeming as though Erdoğan had welcomed expanded freedoms, he has backpedaled quite a bit in the last few years. The increasingly divisive leader has become known for his strongly polemical, even conspiratorial, attacks on dissidents. He has routinely charged opponents with serving outside agents and supporting terrorists and has grown seemingly paranoid over opposition. Earlier this week, the German ambassador was summoned over a song that appeared on German television mocking the Turkish leader and his policies.

It's in such an environment that Turkey has become one of the world's greatest jailers of journalists. Reporters Without Borders ranked Turkey 149th out of 180 countries for press freedom in 2015. Under a controversial law, nearly 2,000 people have been prosecuted for allegedly insulting the president since 2014. In recent months, with renewed fighting against the Kurds, Erdoğan has also gone after mainstream opposition parties, accusing members of the popular Republican People's Party of being "terrorist sympathizers."

The U.S. has routinely raised concerns over freedom of expression, and Ambassador John Bass has reportedly become a loathed figure among supporters of the ruling party. Biden criticized Turkey's record for intimidating journalists and academics, saying it set a poor example in the region.

"We don't always agree on everything — media freedom is one of them," U.S. State Department spokesman John Kirby recently said.

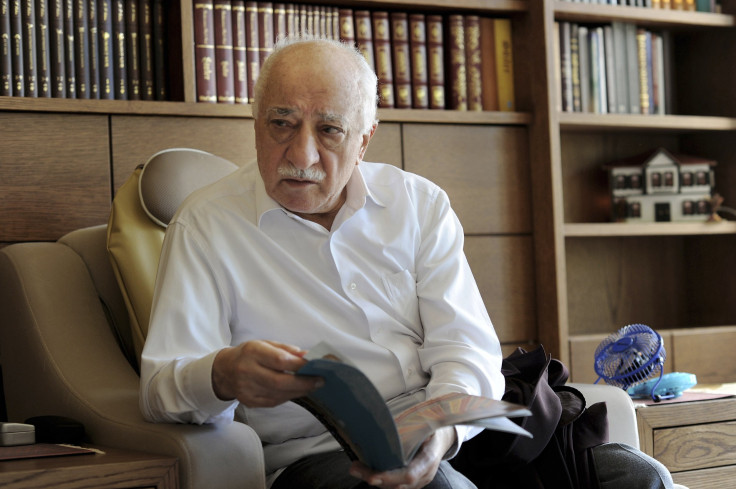

A Rift With an Old Ally. At the center of Erdoğan's alleged repression is an aging, reclusive religious cleric in the Pocono Mountains of eastern Pennsylvania. Fethullah Gülen, 74, leads a popular Islamic movement that emphasizes pluralism and interfaith ties, has millions of followers and a massive business network worldwide. Erdoğan charges Gülen of pushing the country's judiciary and police force to open a massive graft probe that threatened the ruling AK Party in December 2013.

Erdoğan alleges Gülen, once an ally against the country's old secular elite, sought to stage a coup, prompting a major hunt for his supporters nationwide. Gülen himself has lived in self-imposed exile in the U.S. since the 1990s. Erdoğan has been seeking his extradition.

Gülen's institutions across the country have come under heavy pressure and thousands of people have been purged from the police force and military for allegedly being aligned with the quiet cleric. Some of the country's biggest media outlets, including Zaman, the most widely read daily that is also affiliated with Gülen's movement, have been placed under government control, and hundreds have been arrested on a range of charges. Gülen's movement is relatively well connected in Washington and regularly reaches out to the media to air its concerns over Erdoğan's policies. They say Erdoğan has exploited fear of the movement to rid his opponents of influence.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.