300,000-Year-Old Hearth Found In Qesem Cave; Ancient ‘Campfire’ Sheds Light On Human Culture [PHOTOS]

Humans may have discovered fire more than a million years ago, but a recent discovery may shed light on how ancient humans came to control the element and use it in their daily lives.

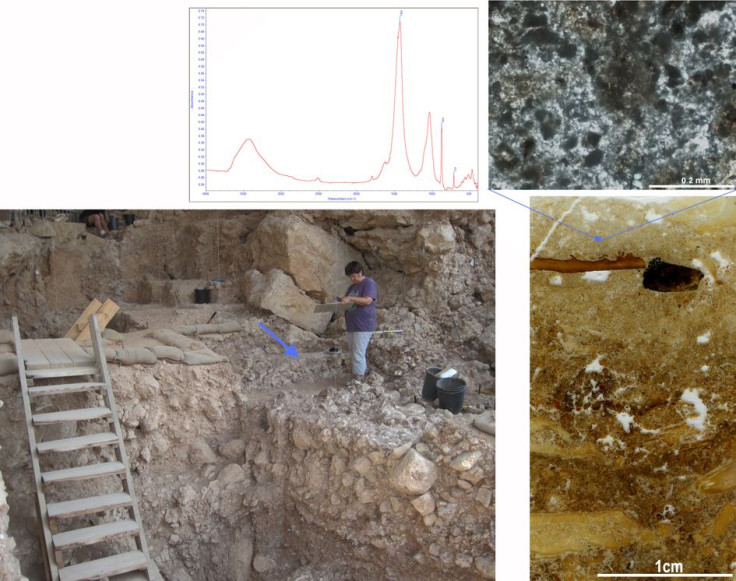

A 300,000-year-old hearth has been unearthed in Qesem Cave, an archeological site located seven miles east of Tel Aviv, Israel. The findings, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, describe how scientists analyzed a thick deposit of wood ash inside the cave using infrared spectroscopy that contained bits of bone and soil heated to high temperatures.

“These findings help us to fix an important turning point in the development of human culture -- that in which humans first began to regularly use fire both for cooking meat and as a focal point -- a sort of campfire -- for social gatherings,” Dr. Ruth Shahack-Gross of the Kimmel Center for Archeological Science at the Weizmann Institute, said. “They also tell us something about the impressive levels of social and cognitive development of humans living some 300,000 years ago.”

The team also tested the micro-morphology of the ash to determine that the hearth was 6.5 feet in diameter at its widest point and was used repeatedly over time.

Around the hearth, the team discovered remnants of stone tools, suggesting they were used for killing small animals and cutting meat. Tools found in areas just feet away from the hearth were shaped differently, which suggests that ancient humans had some form of organized spacial and social order -- a base camp to which prehistoric humans could return repeatedly.

This isn’t the first time signs of fire were found in Qesem Cave. Excavators have uncovered ash deposits and butchered bones that were up to 400,000 years old. In 2010, a paper describing teeth found at the site dating back to 200,000 and 400,000 years ago sparked controversy when coverage surrounding the discovery suggested they belonged to Homo sapiens. The assertion contradicted the popular theory that Homo sapiens arose in Africa 200,000 years ago.

Avi Gopher, an archeologist from Tel Aviv University and a co-author of the paper, said the paper could not conclusively determine to what species the teeth belonged, but they did not rule out the notion they belonged to ancient humans.

“What I can say is that they definitely leave all options open,” he told Nature. “There's been a tendency for people to get so accustomed to the ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis that they use it exclusively and explain any finding that doesn't fit it as evidence of yet another wave of migration out of Africa.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.