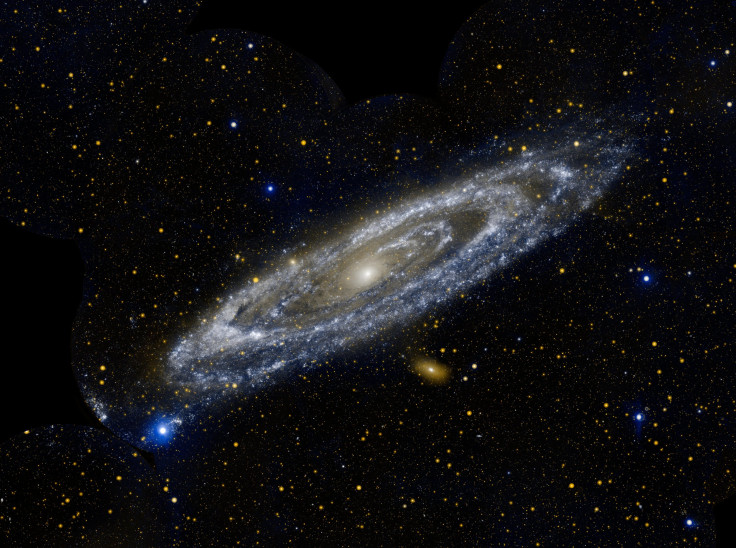

Andromeda Galaxy Shredded Milky Way’s Massive Sibling Some 2 Billion Years Ago

Galactic dynamics are difficult to understand. We don’t exactly know how the Milky Way, its neighbor Andromeda and dozens dwarf galaxies came together to form what we call as the “Local Group,” but every now and then, we get some new evidence that provides more insight into the history of this humongous galactic grouping.

In one such development, a team of researchers found the Milky Way once had a sibling, a galaxy that would have made the third largest member of the Local Group, if not destroyed and shredded by the bigger Andromeda some two billion years ago.

"Astronomers have been studying the Local Group — the Milky Way, Andromeda and their companions — for so long. It was shocking to realize that the Milky Way had a large sibling, and we never knew about it," Eric Bell of the University of Michigan's Department of Astronomy, one of the researchers behind the discovery, said in a statement.

Bell and colleagues at the university suggested the presence of this galaxy, now named M32p, after piecing together the evidence found in the proximity of Andromeda – a nearly invisible halo of stars bigger than the spiral galaxy itself and its enigmatic satellite galaxy, M32 or Messier 32.

For years, scientists observing Andromeda’s faint outer halo posited the region contained remnants of several smaller galaxies that collided with the spiral galaxy throughout its life. But, as this theory made it difficult to understand the features of any one of them, the team ran a series of sophisticated simulations.

The work revealed despite consuming hundreds of smaller galaxies, the majority of stars contributing to Andromeda’s nearly invisible halo came from a single massive galaxy.

"It was a 'eureka' moment,” lead author Richard D'Souza said in the statement. “We realized we could use this information of Andromeda's outer stellar halo to infer the properties of the largest of these shredded galaxies."

So, the team combined information with all available knowledge of M32, a satellite galaxy orbiting Andromeda, and came to the conclusion that Milky Way once had a galactic sibling. They found it was probably 10 times bigger than any other galaxy that collided with ours, but was annihilated after interacting with Andromeda.

The collision shredded the sibling galaxy, leaving just the invisible halo of stars and its surviving center, which we now see as the compact but dense M32 galaxy.

"M32 is a weirdo," Bell added. "While it looks like a compact example of an old, elliptical galaxy, it actually has lots of young stars. It's one of the most compact galaxies in the universe. There isn't another galaxy like it."

Previous studies suggested massive galactic collisions like the one seen here could destroy galactic disks and form elliptical galaxies. However, Andromeda’s disk survived even after the massive collision with Milky Way’s sibling — a fact that challenges the conventional notion. Further studies could provide more insight into this and reveal how big galaxies survive such mergers.

The discovery of the system was detailed in a study published July 23 in the journal Nature.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.