Asian Air Disasters Show Need To Livestream Black Box Data Like Netflix Streams Movies

Air France Flight 447 departed Rio de Janeiro the night of May 31, 2009, bound for Paris with 228 souls aboard. It never made it. The jetliner plunged into the Atlantic Ocean midflight, killing all passengers and crew. Data recovered from the black box showed a problem with the A330’s airspeed indicator -- information that airlines have since used to make modifications that could prevent similar accidents. But the box was almost never recovered, so the industry is now looking for ways to ensure that investigators get critical flight data even in cases where the aircraft is lost forever.

Several manufacturers have developed technology that would allow an airliner to stream information captured by the black box, more formally known as the in-flight data recorder, to ground stations while the plane is still in the sky. It’s an approach that makes sense in an era when movies, music and other content are commonly streamed over the Internet. The push to bring such technology to market became more urgent after the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 earlier this year, and the wreck of AirAsia Flight 8501, which went down Sunday and wasn't found until Tuesday.

“We’re not just working on it, we’ve had it since 2009,” Matt Bradley, president of FLYHT Aerospace Solutions, of Calgary, Alberta, said. Bradley flew F-18 fighter jets in the Royal Canadian Air Force, as well as A320 and A330 aircraft for civilian airlines. He’s been working on better ways to get flight data from airplanes for more than a decade. Then AF447 happened. It took almost two years for investigators to locate and recover the aircraft and the black box under 13,000 feet of ocean. “All of a sudden there was a lot of interest in our technology,” Bradley said.

FLYHT’s FlightStream system uses onboard components to capture black box data and send it to satellites operated by McLean, Virginia-based Iridium Communications. The satellites then use Internet protocols to transmit the data, which also pinpoints a plane’s last-known location, to ground stations. A data stream is automatically triggered if the aircraft exceeds normal flight parameters, or if there's an in-flight anomaly such as a cabin depressurization. Cockpit and ground crews can also trigger the stream if they suspect something is amiss.

Canada’s First Air, which suffered a fatal crash in the remote north in 2011, is now a customer. “With search and rescue in the frozen north, you have to get there fast,” Bradley said.

Canada’s vast land mass has made it a hotbed of sorts for startups working on aircraft tracking and locating technology. Star Navigation Systems, of Toronto, also has a system that streams black box data to ground stations through the Iridium network. The company has Federal Aviation Administration and Transport Canada certifications to use its technology on a range of Boeing and Airbus aircraft. Skyservice, a Montreal-based charter operator, plans to implement the system next month on its Learjet 45 aircraft. “The black box is reactive; what we have is proactive,” Viraf Kapadia, chairman and CEO of Star Navigation, said.

Star Navigation’s STAR-ISMS system not only can transmit black box data but also can send information that can help ground crews plot the most fuel-efficient routes and gain other operational efficiencies. Kapadia got the idea while working as an accountant at a charter airline in the Middle East more than two decades ago. “The air crews were not very good at keeping up their log books so I thought there must be a way to automate the process” of recording maintenance and other issues.

The black box dates to 1953, when Australian inventor David Warren developed the technology after losing his father in a crash. At the time, the boxes were literally black to protect the internal film from the sun. Computer chips have long since replaced film, and the boxes are now bright orange so they can be more easily spotted in a wreck. Among the 256 data points captured is information about engine settings, flap configurations and cabin pressure.

Most black boxes in use by commercial airlines are manufactured by L-3 Aviation Recorders, of Sarasota, Florida. Products from companies like FLYHT and Star Navigation aren't likely to put L-3 out of business any time soon.

Airlines are free to supplement their safety protocols with streaming systems, but until the FAA and other industry regulators say otherwise, they must still have black boxes on their aircraft. That only makes sense. The streaming platforms are in their infancy and have limitations.

Star Navigation’s data stream goes back 45 seconds prior to an in-flight event, while FLYHT’s reaches back two minutes. Bradley admitted that may not be long enough to give investigators a full picture of what caused a crash. “It’s not yet meant to be a replacement for the black box and we are not advocating that it would be enough to do a full accident investigation.”

Expense is another issue. The FLYHT and Star Navigation systems cost about $100,000 to implement, per aircraft. That’s not much considering that the typical Airbus sells for more than $90 million. And ongoing maintenance and data streaming expenses aren't much more than the average consumer might spend in a year on cell phones.

But most airlines operate on razor-thin margins, with industry profits averaging about $6 per seat, according to the International Air Transport Association. “There are a number of other complexities that would also have to be addressed, including for example, storage and ownership of the data,” an IATA spokesman said, adding that the group is working with airlines and aircraft manufacturers to study the practicality of streaming systems.

But both Kapadia and Bradley are convinced that it’s only a matter of time before aviation regulatory bodies around the world start mandating the use of systems that stream black box and other crucial data to the ground while planes are still in flight.

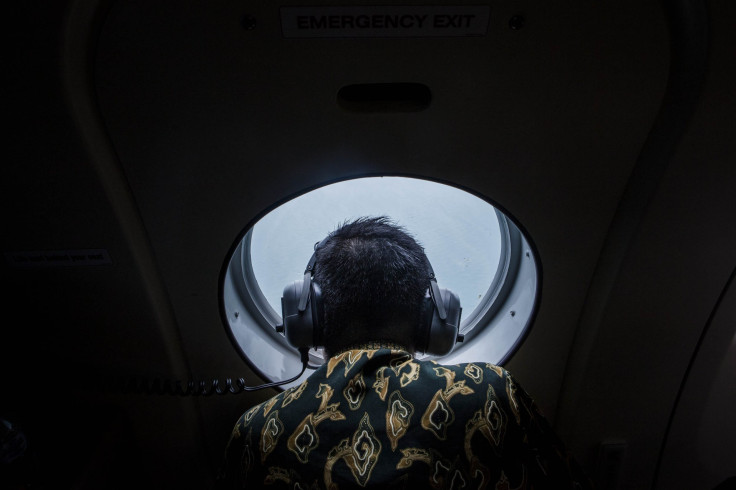

“As they start pulling bodies out of the Java Sea, these questions are going to be asked,” Bradley said, referring to the ongoing AirAsia recovery option. Flight 8501 was the latest deadly crash in 2014, a year that also saw Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 shot out of the skies above the Ukraine and at least two other significant crashes. All told, major airline crashes claimed more than 1,100 lives in 2014. Advocates say better, more easily recoverable black box data could help prevent future disasters.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.