Austerity Push in Greece Leaves Citizens Hungry for Alternatives

News of the latest fiscal rescue for Greece was greeted this week with a deep sigh of relief in Brussels.

Officials in the Belgian capital, after tense, all-night negotiations, hammered out a bailout totaling €130 billion as well as a planned bond swap. The deal, which almost didn't happen, was hailed by Jean-Claude Juncker, head of the group of euro zone finance ministers, as securing a Greek future in the euro area. It reduces privately held debt in Greece's government by €100 billion and saves the ailing Mediterranean state from default, at least for now.

In exchange, the Greeks had to promise a range of devastating cuts, including reducing the country's minimum wage by 22 percent and laying off 150,000 public-sector workers by 2015.

But with Greece's economy shrinking, public support for the austerity-centered deal is crumbling, even as a huge majority of Greeks continues to favor keeping their country in the 17-member euro zone. Greece saw its gross domestic product decline by 6.8 percent in 2011, and a contraction of at least 4.3 percent is expected this year. By 2013, the Greek GDP-to-debt ratio is expected to peak at a staggering 168 percent .

When faced with these dire economic numbers, European officials are increasingly aware that the bailout seems to be putting off an inevitable default.

The austerity measures it will have to implement, and increased monitoring by the troika amidst public outrage will make things harder and drive it deeper into recession, Jennifer McKeown, a senior European economist at Capital Economics, told Reuters. She also said there's a risk that Greece will exit the euro zone later this year. The troika is the three-member group -- the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund -- behind the Greek bailout.

The pattern of decline is repeated to a greater or lesser extent across all austerity-gripped euro zone nations as those with the strictest spending controls in place experience the highest increases in debt, according to the Associated Press Global Economy Tracker.

Ireland saw its debt-to-GDP ratio soar to 105 percent as of last year's third quarter, from 88 percent in 2010. In Britain, government debt reached 80 percent in the third quarter of 2011, up from 74 percent from the same period a year earlier.

Spain provides another example. After implementing its own program of cuts, public-sector wage freezes and tax increases, the country now has an unemployment rate of 21.5 percent -- one of Europe's highest. According to a recent report by Capital Economics, another deep and prolonged slump is on the cards for the Spanish economy. And with longer-term fundamentals such as labor income (down 10 percent from its pre-recession peak) and consumer spending (down 1 percent in the fourth quarter) continuing to fall, the dire predictions seem justified.

The report's authors agree with the IMF assessment that the Spanish economy will contract by 1.5 percent in 2012. But unlike the Fund, they conclude this will lead to an even greater slump in 2013, causing Spain to miss its budget deficit goals and forcing its government to seek Greek-like aid from its partners in the euro zone.

Aside from Greece and Spain, Portugal illustrates the austerity conundrum starkly. The country diligently obeyed every austerity demand, slashing spending across the board to qualify for a €78 billion bailout in May last year.

The reward for all those painful cuts? Portugal's ratio of debt to GDP has gone from an unsustainable 107 percent in 2011 to a worse 118 percent this year. And as long as the economy continues to contract, that gap will continue to widen.

If Europe is to dig itself out of the debt hole, argues Princeton economics Professor Markus Brunnermeier, its focus should shift from austerity to broad-ranging structural change in problem countries.

There are a lot of structural changes that need to be pushed through; for instance, in Greece you have to build up an administration to collect taxes, he says. You can have structural change without austerity measures, it is a fine balance with each country.

The structures in these countries remain the real problem, says Martin Zonis, an expert at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business. I'm stuck by how difficult it is to be a legal entrepreneur in Italy, for instance -- it is so hard to start a business legitimately that many entrepreneurs either give up or operate illegally.

Austerity, however, stifles the impetus for such reforms, Zonis and others explain. As a government presides over an ever-shrinking economy, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to create the space for change. No one wants to fiddle with the tax structure or overhaul competition laws while Rome -- or indeed Athens, Madrid and Lisbon -- burns.

By making the economies worse, people lose their appetite for changing the system, and as governments continue to weaken they too have no mandate to implement change, Zonis says. All of this [austerity] is very short-sighted.

While government ministers in Europe sing from the austerity hymnal, they ignore real danger lurking in the shadows. As the euro zone economies contract, an increasing number of unemployed people will flee mainstream politics, casting their lot with hard-line parties that, at a minimum, oppose the austerity measures.

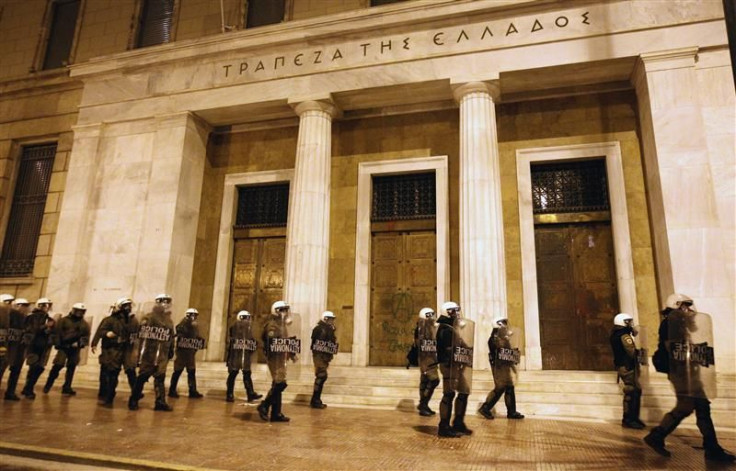

In Greece, a recent Reuters opinion poll showed that support for the two mainstream, pro-bailout parties, Pasok and New Democracy, had hit an all-time low.

At the same time, support for the anti-austerity Left Coalition and Democratic Left parties has risen, with some Greeks contemplating the option of the far-right nationalist Golden Dawn party in the next national elections, set for April.

People are really thinking of this crisis in terms of the interwar years, said Harold James, a professor of European history and economic crises at Princeton. You can see this in Greece with their populist parties: People are looking for a radical alternative.

With European leaders likely to continue to prescribe austerity as the medicine for excessive national debt, it's equally probable that the populations of countries taking that medicine will grow more disillusioned and restive -- in the street and at the ballot box.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.