Bank Of England Cracks Down On Cheating Banks

Banking scandals trigger a regulatory overhaul

The Bank of England (BoE) is cracking down on large financial institutions to prevent them from cheating businesses and consumers worldwide, a practice that has put the $360 trillion global financial market at serious risk for several years.

The push for regulatory reforms aims at divorcing investment banking from retail banking and fixing Libor rates on the basis of actual transactions rather than rates estimated by banks to determine how much it would cost them to borrow from each other in different currencies and time frames.

The Libor is one of the most important interest rates that banks depend on to lend money to one another overnight. How much banks borrow from each other directly affects the public because the interest rate at which they lend money to one another is used to set the interest prices of credit cards, mortgages and other loans.

There is a flood of evidence that banks have been colluding to rig the Libor in the hope of strengthening their trading positions and reaping windfall profits.

Manipulating the Libor by an extremely small number can still change the value of financial products, trading off the falsified Libor, placing a lifelong financial burden on many borrowers, as in the case of Waheeda Bashir, a 35-year-old UK-based halal business owner who was slammed with a debt of nearly £8,000 ($12,546) every month and an additional bill of £19,000 ($29,796) every quarter, when she approached Barclays for a 25-year business loan for £1.25 million ($1.96 million) in 2006. She was told she would not get the loan if she didn't buy an interest rate protection product.

It is a rope around our neck, Bashir told the BBC in a recent interview. We have had to sell all the jewellery that my mum and dad gave to us. It has taken all our life earnings.

What you need is a data repository where the banks have to report actual trades to each other, said Peter Went, a senior vice president at the Global Association of Risk Professionals, a not-for-profit association of risk professionals worldwide.

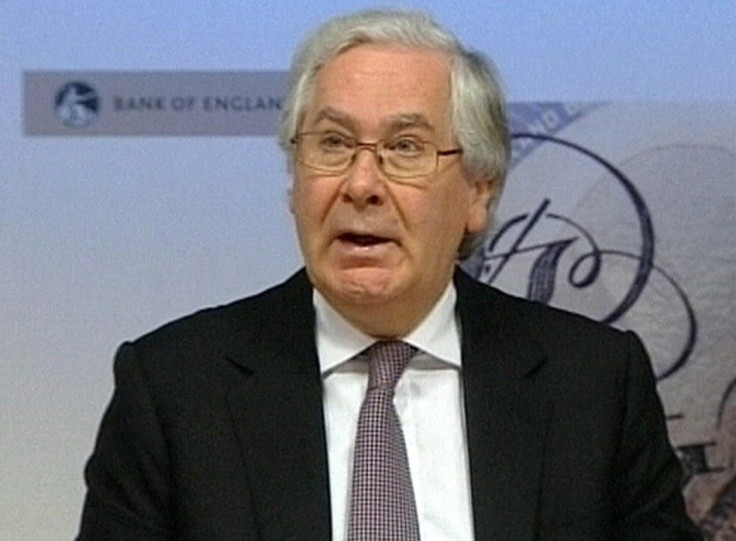

The BoE Governor Mervyn King's announcement came on Friday, the same day that four of the biggest UK banks -- HSBC, Barclays, Lloyds and the Royal Bank of Scotland -- were caught in the act of selling unsuspecting small businesses for financial insurance products they didn't need. Just two days before the announcement, Barclays agreed to pay settlement fines of £293 million ($451 million) to U.S. and UK regulators for rigging the Libor and its Europe equivalent, Euribor.

If we leave it to the bankers to decide that rate, they're going to screw us all, said Ann Pettifor, a director of Prime Policy Research, a macroeconomic think tank based in London. I am in favor of the Bank of England being the body that sets the rate.

Even as Barclays CEO Bob Diamond faces pressures to resign over the benchmark rate scandal, traders at the bank have been found to manipulate the Libor as early as 2005. The bank also tried to curtail Libor rates, resulting in a situation where taxpayers and customers could potentially have lost millions because interest rates were lower than they should have been.

The Bank of England is urging banks to disclose their current assets, liabilities and off-balance sheet exposures as a measure to discourage them from influencing the Libor by cherry-picking trades. Such a requirement will provide a more accurate representation of borrowing costs -- something that will be fairer for taxpayers and savers who are already reeling from the impact of the coalition government's austerity measures.

A move to benchmark rates based on actual contracts could be gradual, some economists say. Libor reform protesters claim that substantial changes in the regime could affect existing contracts that reference the Libor. King's recommendations to ring-fence retail banking from investment banking could also jeopardize London's position as the world's financial capital, taking British banking back to the 1970s, Harry Wilson, an analyst and business reporter told The Telegraph in an interview.

The Bank of England is not the only regulator to whip financial institutions. Watchdogs around the world are putting pressure on the British Bankers Association, the UK's financial trade association, to restore credibility to the Libor after they launched a probe into possibilities of a covert agreement among traders seeking to profit from bets on derivatives by swaying the rate.

One thing you don't want is a long, drawn-out process, an economist told IBTimes. We need the authorities, the BBA and various institutions to get on with it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.