Between The Lines Of The Panama Papers: How The Offshore Tax Scandal Robs Developing Countries

The people hardest hit by the kinds of shadowy financial transactions mapped out in the recently leaked Panama Papers may never even know it.

As revelations emerge from the enormous cache of documents about how the rich and powerful conceal and protect their wealth in offshore tax havens, some of the politicians named in them have scrambled to deny wrongdoing. Yet between the lines of the Panama Papers’ 11.5 million files are the untold others — the unnamed victims who suffer daily as a result of these diverted funds. They are citizens of developing nations who, thanks to the massive sums — estimates range from $213 billion to $1.1 trillion in a single year — that these countries lose annually to tax avoidance and evasion, are deprived of critical funding for education, healthcare, infrastructure and other fundamental needs, analysts say.

“Those governments just can’t collect enough tax, because their systems are so exposed to abuse from tax havens,” said Richard Murphy, a professor of practice in international political economy at City University London. “They can’t provide healthcare, they can’t provide education, they can’t provide investment in infrastructure,” he added. Ultimately, their citizens pay a hefty price, Murphy said.

The transactions detailed in the Panama Papers, which came from Mossack Fonseca, a Panama-based fiduciary that is a leader in incorporating offshore companies, are not necessarily illegal. For many of the more than 200 players named in or connected with the files, the legal repercussions, if any, remain to be seen.

The watchdog Global Financial Integrity has found that from 2004 to 2013, developing countries lost $7.8 trillion in illicit financial outflows. In seven out of those 10 years, such losses surpassed the amount of official development aid and foreign direct investment combined.

These diverted dollars deprive locals of resources for basic infrastructure and services, from passable roads and potable water to information and communication technologies, reports on taxation in developing countries and tax evasion indicate. When governments can't generate sufficient revenue through taxation, social and economic development programs that improve access to schools and healthcare or empower women lose out, hurting economic development and reducing chances for people to rise out of poverty and rendering countries more dependent on foreign aid.

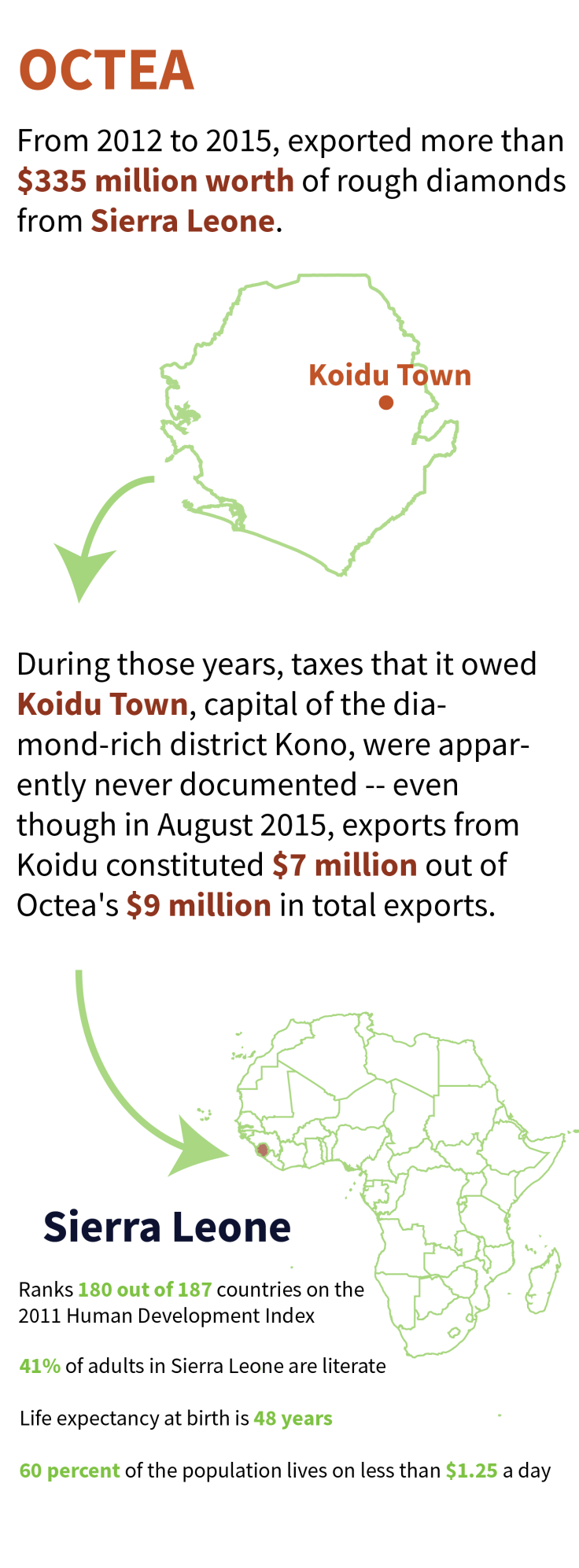

Examples of this abound. The Panama Papers reveal how Octea, an entity based in the British Virgin Islands, was actually owned by Beny Steinmetz Group Resources, a company under investigation for alleged bribery in Guinea. From 2012 to 2015, Octea appeared to have exported rough diamonds from Sierra Leone worth more than $335 million, the African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting found. In August 2015, for instance, exports from the city of Koidu constituted $7 million out of $9 million Octea's in total exports, yet taxes that it owed Koidu were apparently never documented.

Octea also allegedly owes Koidu more than $700,000 in property taxes, the mayor, Saa Emerson Lamina, told ANCIR.

In 2008, none of the major mining companies in Sierra Leone even reported profits, found a report by National Advocacy Coalition on Extractives. Many were registered in overseas tax havens, so even though mining accounted the vast majority of Sierra Leone’s total exports, it constituted less than 5 percent of total export values in 2007. Overall, shortfalls in taxes “could have funded many areas of essential needs met via public services,” the report concluded.

Sierra Leone emerged from a civil war in 2002. Today, it is one of the poorest countries in the world, taking 180th place out of 187 countries on the Human Development Index in 2011, according to the United Nations Development Program.

Barely more than 40 percent of adults in Sierra Leone can read, life expectancy at birth is 48 years and 60 percent of the population lives on less than $1.25 a day. Since 2014, the Ebola epidemic that ravaged West Africa has killed an estimated 4,000 people in Sierra Leone.

“This is a real blight upon the world,” Murphy, the City University London professor, said of tax avoidance and evasion, legitimate or not. “It really does have a domestic impact in developed countries, but in developing countries it’s even bigger.”

Nearly every country in the world is linked in some way to the Panama Papers. From Pakistan to the United Kingdom, the papers point to 12 current or former national leaders, 61 relatives or associates of such leaders and 128 current or former politicians or public officials — and 29 people on the Forbes Billionaires list.

The documents link three children of Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to offshore companies that own prime London real estate and appeared to use those properties as collateral against a loan of $13.8 million, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists reported. That in itself is not necessarily illegal, but using offshore entities can be one tactic to avoid paying taxes. The family is one of the richest in Pakistan and has previously been accused of corruption, tax avoidance and money laundering.

Sharif said in response to the revelations that he had “never betrayed the trust of the nation.”

In Pakistan, per capita annual income falls at $1,368. Roughly a fifth of the population lives below the poverty line. It’s also considered one of the 10 nations most vulnerable to climate change, and over the next four to five decades will have to spend a projected $10.7 billion every year to adapt.

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, who ran for office promising to sell his candy business Roshen and “focus exclusively on the welfare of the nation,” appeared to set up an offshore holding company and register the business in the British Virgin Islands on Aug. 21, 2014 — the same day 27 soldiers were killed in a hailstorm of Russian rockets fired by separatist rebels.

That move, probably illegal since Ukraine bans its presidents from engaging in business activities, might have saved him millions in taxes, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project reported. For Ukraine, this type of problem is a familiar one; from 2004 to 2013, the country lost an average of $11.6 billion every year to illicit money moving, according to the Washington-based watchdog Global Financial Integrity.

For all the questionable activities they lay out, the Panama Papers also offer hope in the form of a story, albeit an exceptional one, from the unlikely setting of Uganda.

In 2010, the company Heritage Oil and Gas Ltd. sold its 50 percent stake in Ugandan oil fields to the company Tullow Uganda for $1.5 billion, the South Africa-based Times Live reported. The Uganda Revenue Authority taxed the transaction at a capital gains rate, so that Heritage owed the government $404 million.

The company attempted to "wriggle" out of paying the tax by moving its official address from the Bahamas to Mauritius, which with Uganda has a double tax agreement, the Panama Papers showed. It took four years of court battles in at least two countries, but in the end, Uganda won and collected its dues.

It was, the Times Live wrote, “an exceptionally strong act of political will.”

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.