Ceres' Mysterious Bright Spots Are Most Likely Salt And Water

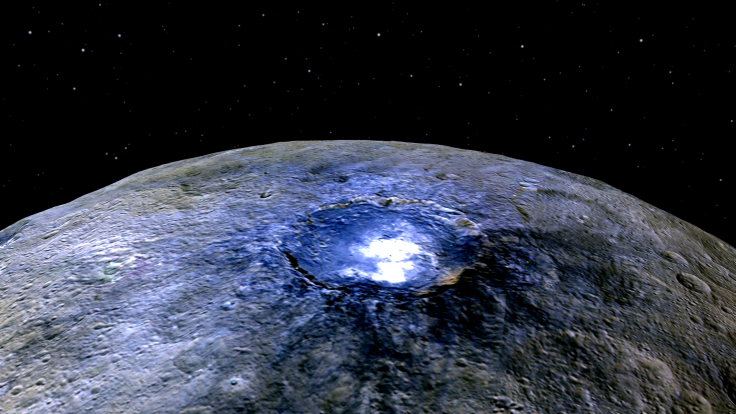

Since March, when NASA’s Dawn spacecraft entered into orbit around Ceres -- a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter -- a clump of bright spots on its surface has mystified scientists. Now, after weeks of frenzied speculation, a study published Wednesday in the journal Nature has the answer to what might be causing these spots to glimmer.

In one of the most detailed surface analysis of the dwarf planet to date, authors of the study argue that the spots are a mixture of salt and water-ice.

High-resolution maps of Ceres have shown that the generally dark surface of the dwarf planet has over 130 bright areas, most of which are present in impact craters. In October, Dawn's principal investigator Chris Russell said that while he and his colleagues believed these bright spots to be a result of light reflecting from a huge salt deposit, “we don't know exactly what salt.”

According the authors of the study, the bright material seems consistent with a type of magnesium sulfate -- an inorganic salt -- called hexahydrite. These minerals are also found on Earth -- occasionally at the rim of salt lakes. A different type of magnesium sulfate present on Earth is Epsom salt.

“The global nature of Ceres’ bright spots suggests that this world has a subsurface layer that contains briny water-ice,” lead author Andreas Nathues, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen, Germany, said in a statement. “We are currently probably seeing remnants of an evaporation process exhibiting different stages in different locations. Perhaps we are witnessing the last phase of a formerly more active period.”

According to this theory, impacts from asteroids might have unearthed the mixture of ice and salt, exposing them to the surface, where they appear as bright spots.

However, as water-ice has not been detected on Ceres so far, higher-resolution data would be needed to settle the question.

Also on Wednesday, a separate study published in Nature raises questions about how Ceres formed, hinting that the dwarf planet may have originated not in the asteroid belt, but in the outer solar system.

For the purpose of this study, a team of scientists used data from the visible and infrared mapping spectrometer to analyze the composition of Ceres. Surprisingly, they found evidence of ammonia-rich clays, or ammoniated phyllosilicates, on the surface, indicating that Ceres might have formed somewhere near the orbit of Neptune where nitrogen ices are thermally stable.

“The presence of ammonia-bearing species suggests that Ceres is composed of material accreted in an environment where ammonia and nitrogen were abundant. Consequently, we think that this material originated in the outer cold solar system,” lead author Maria Cristina De Sanctis, a scientist at the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome, said, in a statement.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.