Climate Change: Are Rising Carbon Dioxide Levels Causing Rapid Plankton Growth?

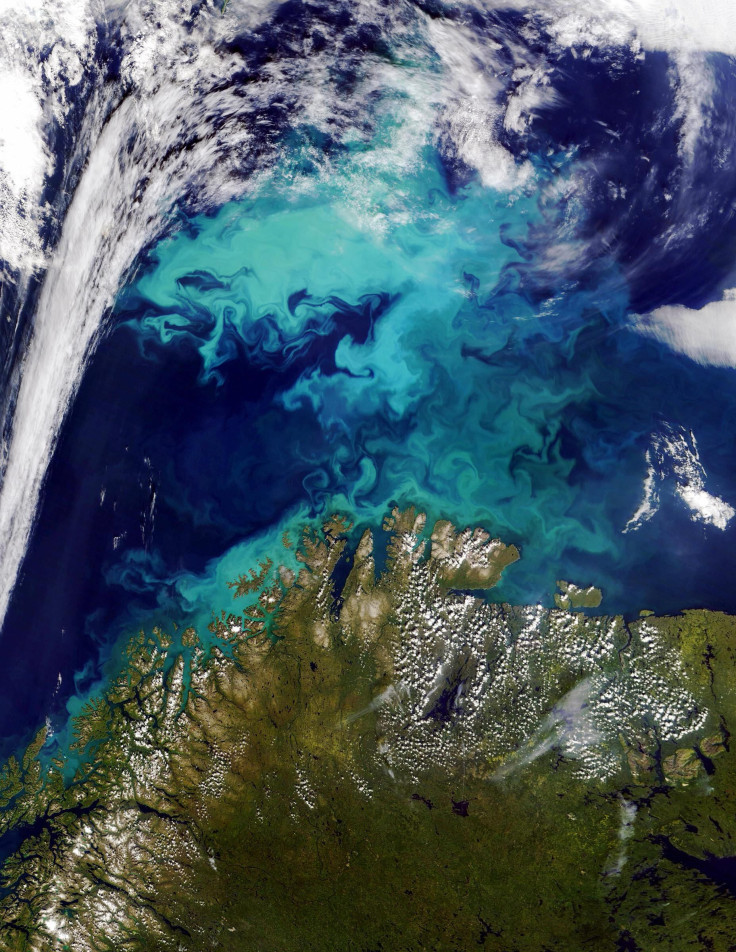

A marine alga in the Atlantic Ocean is thriving beyond scientists’ predictions, suggesting that increases in carbon dioxide levels -- thought to be one of the major causes of global warming -- are creating fast environmental changes, scientists at Johns Hopkins University reported. From 1965 to 2010, the level of single-celled coccolithophores has increased tenfold, disproving a previous theory that such organisms would decrease with rising ocean acidity.

Scientists have yet to determine what exactly the increase in this type of phytoplankton means, or if it is a good or a bad thing for the Earth, a news release from the university said. The results do suggest ecosystems are changing at a more rapid rate than previously thought, and the models used to measure the effects of climate change may not be adequate.

"Something strange is happening here, and it's happening much more quickly than we thought it should," Anand Gnanadesikan, a Johns Hopkins associate professor and one of the study's five authors, said in a statement. “What is worrisome is that our result points out how little we know about how complex ecosystems function."

The analysis of coccolithophores is part of a survey of plankton that has been going on since the 1930s. Gnanadesikan has run models in the past to see how phytoplankton respond to changes in carbon dioxide, but the responses weren't as striking as the increases shown in the recent survey, the Independent reported. Such a strong increase of coccolithophores makes Gnanadesikan worry for the future.

Rising Carbon Dioxide Causes Rapid Growth of Coccolithophores in the Ocean https://t.co/QZCcJGO2JB pic.twitter.com/APhYVOtzqG

— Science World Report (@sciencewr) November 28, 2015“So it makes me wonder what we've missed, and whether other surprises in the works may be less benign,” Gnanadesikan said, according to the Independent.

Coccolithophores have been abundant in warmer periods of history between ice ages. Because of the rise of coccolithophores now, it could indicate a bigger climate change is going on, said William Balch, senior research scientist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Science in Maine, the Independent reported.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.