'David-And-Goliath' Merger: Astronomers Delve Into Origins Of Uneven Black Hole Merger

KEY POINTS

- In April 2019, researchers spotted a black hole merger wherein one is much bigger than the other

- Researchers of a new study ran simulations to see which merger scenario fits GW190412

- It's possible that the larger black hole was a result of an earlier merger between two parent black holes

Researchers are offering an explanation for the merger of two black holes wherein one is much bigger than the other.

Black hole mergers typically happen in two ways: the envelope process and dynamical interactions. Under the envelope process, two neighboring stars explode to form black holes that share a common envelope. Eventually, these two black holes merge together to form a bigger one.

In the dynamical interactions method, multiple black holes in a certain region may "change partners" multiple times before a pair finally goes on to merge.

In both of these scenarios, the black holes have roughly the same mass. But researchers of a new study found an unusual black hole merger wherein one black hole is significantly larger than the other.

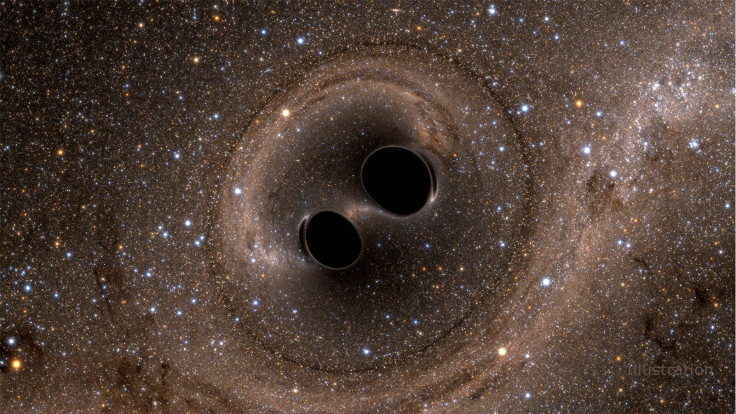

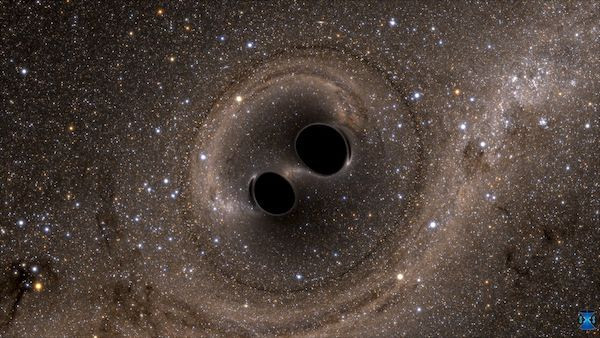

First detected on April 12, 2019, the signal, dubbed GW190412, was spotted by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo and, was determined to be from the merger of two black holes. But researchers noticed that the merger was between a black hole and another one that's three times more massive, making it the first ever observation of an unequal-mass black hole merger.

In the study, published in the journal Physical Review Letters on Wednesday, the research team demonstrates that the "David and Goliath" merger is unlikely to have happened through the two known ways but due to a hierarchical merger wherein the larger black hole also formed from an earlier merger.

Using two models, the researchers tried to match GW190412's merger with the known black hole merger processes but neither could explain the merger better than a hierarchical merging.

"No matter what we do, we cannot easily produce this event in these more common formation channels," study co-author Salvatore Vitale of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) said in a news release. "The bottom line is, both these scenarios, which people traditionally think are ideal nurseries for black hole binaries in the universe, struggle to explain the mass ratio and spin of this event."

The researchers also determined that if GW190412 was indeed formed through hierarchical merging, the initial collision that formed the larger black hole likely would have occurred in an environment with an intense gravitational pull.

Otherwise, the initial collision would have just kicked the resulting black hole out of the cluster where it won't be able to merge again. But since it did stay and possibly formed GW190412, that could mean the kick was not strong enough for the initial black hole to escape.

The scenario of a hierarchical merger has been hypothesized before but little to no evidence of it has been captured.

"This event is an oddball the universe has thrown at us — it was something we didn't see coming," Vitale said. "But nothing happens just once in the universe. And something like this, though rare, we will see again, and we'll be able to say more about the universe."

This week another team of astronomers, who were also using LIGO and Virgo, published their findings of another possible hierarchical black hole merger, dubbed GW190521. It was so massive that it could also be the first evidence of intermediate black holes.

The discovery of GW190412 and GE190521 provides several firsts, including possibly the first evidence of peculiar hierarchical black hole mergers.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.